![]() Part I: Struggles for Empire in Peace and War, 1762–1787

Part I: Struggles for Empire in Peace and War, 1762–1787![]()

Prologue: The Open and Hidden Features of Peace

Louisiana, Florida, and the Imperial Settlement of 1762–1763

On January 13, 1762, Charles Wyndham, second Earl of Egremont, sent momentous instructions from his majesty’s privy council to General Jeffrey Amherst, commander-in-chief of British forces in North America. The long war against France had just entered a new stage. Great Britain was now in conflict with Spain, too, and therefore intending to strike at Madrid’s overseas possessions. The English decision for war answered King Carlos III’s renewal of the Bourbon Family Compact—the dynastic alliance between the Spanish and French monarchs aimed at humbling their common British enemy.1

Amherst’s orders were to dispatch 4,000 British regulars and American provincials from New York City to support an amphibious assault on Havana. Once that key to the Antilles had fallen, Sir Jeffrey was to embark from New York with another 8,000 men in a maritime invasion of French Louisiana—a province considered by Egremont to be “both a desirable and a practicable Object of Attack.”2 Commanding the Cuban expedition, George Keppel, Earl of Albemarle, had license to continue his offensive beyond Havana, and to proceed against St. Augustine in Florida, Santiago de Cuba, “or any other part of the Spanish Colonies” he thought could be taken.3

Albemarle achieved Havana’s capture on August 14, 1762, but at such a heavy cost that additional conquests were unthinkable. Besides casualties through fighting, British forces lost 4,700 soldiers and sailors to yellow fever and other illnesses within six weeks of Havana’s capitulation.4 As English transports staggered from Cuba to Manhattan’s dockside in September, ship crews had too few healthy men to drop anchor by themselves. A disappointed but realistic Amherst had no choice except to call off a Louisiana campaign.5 Had tropical diseases not had such a lethal impact, it is possible that British arms could have brought New Orleans into the empire in the fall of 1762. The city’s defenses were weak since soldiers were few, and munitions and foodstuffs in short supply. The Choctaws and Alibamons, usually French allies, chafed at the lack of customary royal gifts. Metropolitan France could scarcely satisfy Louisiana’s needs amidst far greater wartime struggles.6

Because Amherst never set sail for Louisiana, it is easy to overlook the British government’s conception of bringing the Gulf Coast within the imperial orbit of the Caribbean and Atlantic. As in many wars, victories achieved in a central theater—in this case the West Indies—created an impetus to extend conquests to more peripheral zones. Amherst’s projected Mississippi offensive was precisely the type of far-flung military campaign that Spanish officials had dreaded for years. To anxious Bourbon statesmen, English naval and mercantile power appeared boundless, capable of dominating seas from the tropics to the poles.7

Fortunately for Madrid, the British government was not perpetually bellicose. As the siege of Havana was underway, English diplomats negotiated peace terms with French and Spanish representatives in Paris. George III and his first minister, the Earl of Bute, desired an end to an exhausting war. Bute especially feared that a prolonged conflict would restore William Pitt, his dreaded political foe, to power on a platform of belligerent nationalism.8

There was nothing unusual about the dual pursuit of war and peace in eighteenth-century imperial conflicts waged simultaneously in Europe and the Americas. While battles raged, rulers in London, Paris, and Madrid carefully assessed their respective strengths and weaknesses in various geographic spheres. Total victory over enemy states was not to be expected. Territories won by arms might be restored to a foe upon the conclusion of peace, particularly if some commensurate or superior benefit could be extracted. Similarly, defeat in a particular military theater did not preclude regaining lost ground, especially by proffering peace to antagonists whose victories drained national resources. Peace talks commonly stirred as much political contention among allied powers as between hostile nations. This was certainly true in 1762, when France and Spain had borne the brunt of war to such unequal degrees. The duc de Choiseul, Louis XV’s foreign minister, sought to salvage what he could from a long and disastrous conflict. Madrid was far more reluctant to quit the battlefield short of achieving its major national objective—the wresting of Gibraltar from Britain.9

Choiseul, a gifted diplomatist, had no doubt that the West Indies counted far more than North America in the competition for wealth and power. During the summer of 1762, France prepared to cede extensive American territories to Britain in order to recoup captured Caribbean isles, especially Guadeloupe and Martinique. Choiseul was resigned to the loss of Canada. He was also willing to surrender all continental claims east of the Mississippi, apart from New Orleans and vicinity. The lands in question stretched from the Illinois country to Mobile Bay—all part of Louisiana in theory, though in reality largely an Indian country under French influence rather than possession.10

The marqués de Grimaldi, Spain’s foremost negotiator at Paris, felt the sting of French self-interest and British ambition during the movement toward a peace settlement. He could do little, however, to prevent a diplomatic downslide after Havana’s fall. The only question was what price the English would demand in return for evacuating Cuba.11 While some British government ministers aimed for Puerto Rico and Florida, George III finally accepted Florida alone. Spain thereby parted with a financially burdensome colony, which had served in recent decades to halt British incursions from the Carolinas and Georgia.12 The cession was limited but still pregnant of change. For two hundred years, the Spanish presence in Florida shielded the Bahama Channel (the “Florida Straits” on current maps)—a prime corridor for ships sailing with Mexican silver via Veracruz and Havana for Spain. That passage was scarcely secure in the wake of British gains that included Spanish St. Augustine and Pensacola, along with French Mobile. There seemed little left of Spain’s traditional conception of the Gulf (el Seno Mexicano) as an imperial lake foreclosed to foreigners.13

Considering the Bourbon powers’ woes, Choiseul could do no better than to mollify Madrid’s bitterness over a failed war. Prodding Spain to peace, the French minister tendered a royal gift in the name of Louis XV to his younger cousin, Carlos III. On the table was the secret French cession to Spain of New Orleans, the delta lands lying below that city, and all Louisiana west of the Mississippi. Choiseul and Grimaldi concurred on this proposal at Fontainebleau Palace on November 3, 1762, just hours after the two men had agreed to preliminary peace articles with Britain at the same venue. Ten days later, Carlos III formally accepted Louis XV’s tender of Louisiana.14

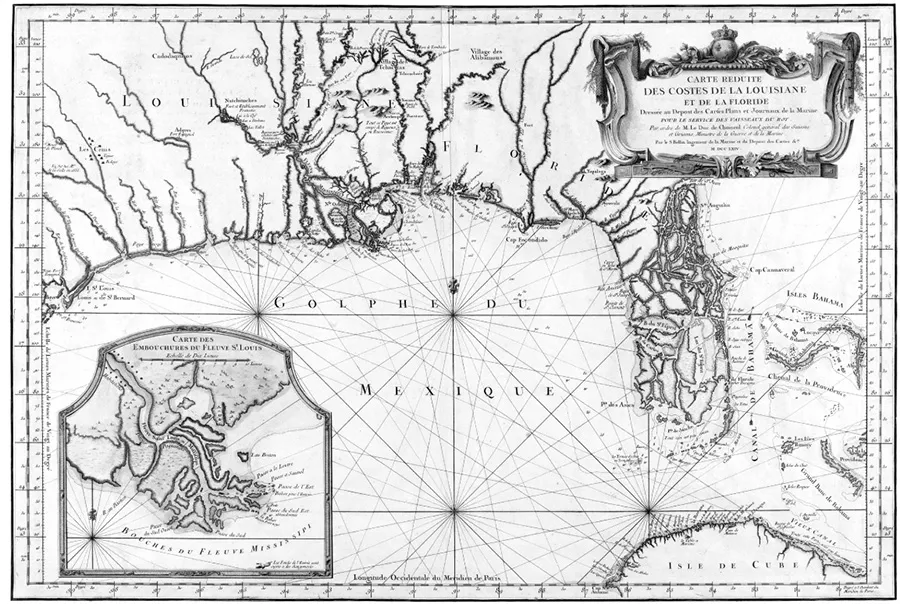

Jacques Nicolas Bellin, Carte reduite des costes de la Louisiane et de la Floride (Paris, 1764). This map shows limited geographic understanding of peninsular Florida, whose land mass is broken by numerous rivers and lakes between the Atlantic and Gulf Coast. The map clearly depicts the “Canal de Bahama”—a prime maritime corridor between Florida’s eastern coast and the Bahamas. Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, acc. no. 1977.66 i,ii.

Spanish military defeat had economic consequences that were as significant as North American territorial adjustments. By the definitive peace settlement of 1763, Madrid confirmed previous Anglo-Spanish commercial treaties, including an accord of 1750 granting Britain most-favored nation status in trade with peninsular Spain. Carlos III had entered the war seeking to abrogate these existing obligations, which hampered domestic industry, encouraged smuggling, and enabled British merchants to siphon profits from Spain’s commerce with its American dominions. The English ranked supreme among foreigners who flouted the law of the Indies by trading with his Catholic Majesty’s overseas colonies. Silver was the great prize, whether gained by consensual transactions or extracted by force in war.15

The European peace settlement of 1762–63 was notable for both its hidden and open features. Indian peoples had no say over imperial decision-making affecting their lives. There was only one point in the Paris peace negotiations when their situation directly entered discussions. As the Spanish court struggled to stanch British expansion, it suggested the creation of a vast trans-Appalachian Indian reserve that would be foreclosed to European settlement. This proposal was summarily dismissed by English foes.16

Native peoples suspected being betrayed by the French king—their supposed “father”—well before official news of European treaty-making came to the Mississippi. In July 1763, the chiefs of several nations—the Biloxis, Chitimatchas, Houmas, Choctaws, Quapaws, and Natchez—arrived at New Orleans to meet Jean-Jacques Blaise d’Abbadie, Louisiana’s director-general. The headmen aired disquieting fears that France had surrendered parts of Louisiana to both Britain and Spain. Abbadie’s journal refers to this meeting, though without noting his response to the visitors. A Cherokee, Choctaw, and Alibamon delegation had already voiced anger over pending French cessions to Britain east of the Mississippi. In early May 1763, Louis de Kerlérec, then director-general, reported the headmen saying openly “that they are not yet all dead; that the French have no right to give them away.” Far to the east Creek spokesmen voiced similar trepidation of pending Spanish departure.17 The rumors circulating in Indian country were quite on the mark. Imperial powers had acted as if they were “lords of all the world,” altering boundaries and transferring native territories “with the scratch of a pen”—to employ phrases aptly used by recent historians.18

While Choiseul made no secret of French territorial concessions to England, he catered to Spanish sensitivities by delaying public notice of Louisiana’s transfer. Madrid was thankful for the respite because it required time to take a new and quite unfamiliar colony under its wing. On April 21, 1764, Choiseul finally dispatched a proclamation to Louisiana announcing the province’s total cession. The notice reached New Orleans that September, arousing colonial shock and despair. Choiseul had long since informed the British government that his king relinquished all interest in Louisiana whatsoever.19

Prior to 1763, French Louisiana extended in theory from Carolina’s western rim to New Mexico’s borderlands, and from the Gulf Coast to Canada. Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz, a French observer who resided in Louisiana from 1718 to 1734, wrote that the Mississippi “divides this Colony from North to South into two parts almost equal.” This conception died with the Treaty of Paris, which defined the river for the first time as an international boundary between imperial states.20

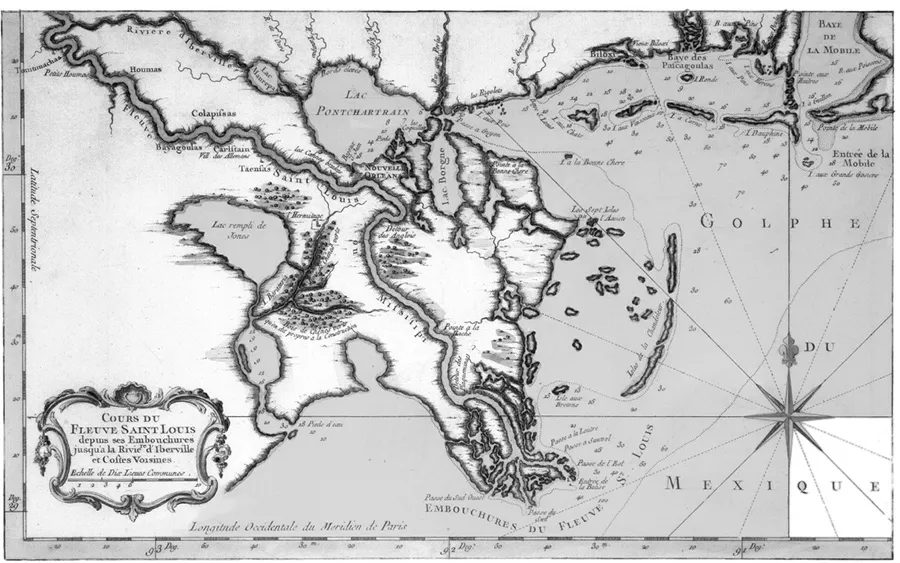

To gain a clearer understanding of the Mississippi issue, we may consult a map drafted in 1763 by Jacques Nicolas Bellin, an accomplished French cartographer. (Bellin labeled the Mississippi by both its Indian name and its formal French title, the River Saint Louis.) Quite strikingly, the map pinpoints New Orleans by a red dot on the river’s east bank just a few miles below bulging Lake Pontchartrain, an oval-shaped waterway with a narrow eastern channel leading to the Gulf of Mexico. The town, then home to some 3,000 residents, occupied a small place within a lengthy expanse of land frequently though not continually encircled by water. Bellin’s map expressed the rather simplistic European view of New Orleans as a city on an island, commonly called the “Isle of Orleans.”21

Jacques Nicolas Bellin, Cours du Fleuve Saint Louis depuis ses Embouchures jusqu’a la Riviere Iberville et Costes Voisines (Paris, 1763). This map depicts New Orleans, and the position of the Iberville River and Lakes Maurepas and Pontchartrain, whose midstream course formed part of the new international boundary established by the Treaty of Paris of 1763. Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, acc. no. 1975.24.

Lt. Phillip Pittman, an English engineer who first visited New Orleans in 1763, described the city’s “situation” as “extremely well chosen.” Located 105 miles above the Mississippi’s mouth, the town was “secured from the inundations of the river by a raised bank, generally called the Levée,” which extended fifty miles from the “Detour des Anglois” (the so-called English turn in the Mississippi’s course) below the city to the Cote d’Allemands (or German coast) above. As Pittman noted, the Levée also served as “a good coach-road” of more than fifty miles. While New Orleans commanded the main Mississippi passage, the city had a secondary point of access via Bayou St. Jean, a narrow waterway near the town’s northern edge. Small vessels plied the bayou to and from Lake Pontchartrain whose eastern channel fed into the Gulf of Mexico.22

During the Paris peace negotiations of 1762, Choiseul hammered out a tentative agreement on the Mississippi with the Duke of Bedford, who insisted that England have navigational ri...