[1]

The Symbolic Vocabulary of Public Executions

Anton Blok

One of the most dramatic changes in the history of European legal systems has been the transition from public executions to imprisonment, which took place at the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth. Although this development has often been discussed (e.g., Foucault 1977) and much has been written on public executions in general, especially with regard to the German territories (e.g., Schild 1980; Dülmen 1984), one would like to know more about the meaning of these forms of punishment, and the reasons that they met with increasing resistance until they finally became intolerable. The sentences given well over 500 members of the robber bands in the Lower Meuse—the so-called Bokkerijders—between 1741 and 1778 may be of interest because they show a development that foreshadows the main transition from corporal punishment in public to confinement in workhouses and prisons. My sources are chiefly court records, which I have supplemented with the correspondence and published writings of contemporary judges, government officials, priests, and other notables. Seeking to decode the messages inscribed in the cultural forms of theatrical punishments, this chapter draws heavily on material I have collected for a forthcoming monograph on the social history of these robber bands.1

The Area

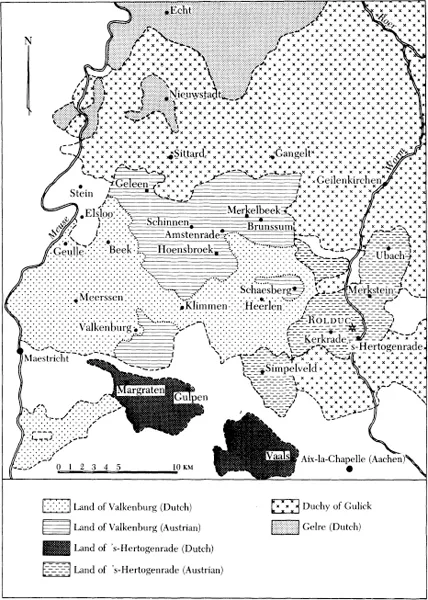

The robber bands operated on the east bank of the Meuse, in the rural districts enclosed by the towns of Maestricht, Aix-la-Chapelle, Gulick, and Roermond. Up to the early eighteenth century, this part of the Lower Meuse had suffered from frequent military operations. The rural population had to feed and lodge armies in transit and in winter camps if there was no chance to pay the military off through expensive sauvegardes. Worse still was the scourge of disbanded soldiers who indulged in looting and plundering villages and farms (see Wouters 1970; Gutmann 1980). Although virtually without protection (except flight), the inhabitants of this frontier area of the Dutch Republic and the Spanish (after 1713, Austrian) Netherlands succeeded in recovering from these afflictions. Between 1650 and 1750, the rural population remained fairly stable in this hilly, wooded, and relatively fertile region of mixed farming where large tenant farms dominated. As elsewhere in Europe, it was only after 1750 that the population of the Lower Meuse started to grow rapidly. Contemporary maps indicate a relatively dense population (about fifty inhabitants per square kilometer) grouped into many small, nucleated villages and towns. Most settlements fell into the pattern of what are customarily called “street villages”; of these, many had originated as Waldhufendörfer; place names ending in -rode, -rade, -rath, -hage, -heide, -veld, and so on, reveal the late-medieval foundation of these settlements as forest- and heath-clearing villages. Access to land was all-important. Broadly speaking, there were two main social classes, each defined in relation to control over land. Exclusion from ownership of land implied social exclusion too (see Slicher van Bath 1963; Roebroeck 1967; Philips 1975; Schrijnemakers 1984).

There were also several industries in the area, not only in the towns but also in the rural villages, which produced textiles, metal, and leatherwork. The entire region, in fact, formed an offshoot of the important industrial concentration around Liege. Apart from agriculture, therefore, people lived off several rural domestic manufacturers and commerce. We know, for example, of an ironworkers guild (gilde van den eyseren) in the district of Geleen that incorporated makers of locks, hinges, chains, harnesses, and scissors. In 1720 the guild numbered 109 members from several towns and villages in one of the Austrian enclaves in the Lower Meuse. Because of falling prices, the guild formed a cartel to fix prices and production quotas. Work stopped during the summer months to allow guild members to find employment in harvest work. The cartel expanded to include ironworkers from other places in the area. By 1740 its membership had grown to 280 ironworkers (Thurlings and van Drunen 1960).

Map 1. Political fragmentation of the eastern Meuse Valley, 1715–1785

At the time this part of the Meuse valley was politically fragmented to a considerable extent (see Map 1). Including parts and enclaves of Dutch and Austrian territories, together with sections of the duchy of Gulick and various autonomous and semiautonomous seigneuries, it was in several respects a border area par excellence. Apart from the political frontiers, there were many different jurisdictions, and the boundary line dividing Protestants from Roman Catholics ran right across the area. The transitional character of the entire region was reinforced by its location on commercial and military crossroads. The Lower Meuse formed a bridgehead in a major European interaction zone—connecting Flanders with the Rhineland, and the Dutch Republic with the southern Netherlands and France. Finally, we should note the extremely peripheral location of the Dutch and Austrian territories with respect to their political centers—The Hague and Brussels. Disconnected from the other parts of the Dutch Republic and the Austrian Netherlands, respectively, these territories were true enclaves (Wouters 1970; Haas 1978).

The Bokkerijders: Background and Operations

Over a period of almost fifty years—from the late 1720s through the early 1770s—various bands of changing size and composition carried out more than one hundred attacks on inns, shops, breweries, and various Roman Catholic churches, rectories, wayside chapels, and in particular tenant farms. All the attacks took place in the area of the Lower Meuse. The size of the bands ranged from a dozen to well over 150 participants. The raids fell into three distinct periods, each of which came to an end with mass arrests, trials, and executions. The first phase, which lasted until the early 1740s, saw more than sixty operations, most of which were directed against churches, while at least ten raids involved massive attacks on farms and rectories. The second phase, which covered only the years 1749–50, included just two outings and was to some extent a short-lived revival of what had remained of the earlier bands. In the third phase, from the early 1750s onward, the ranks of the robbers swelled considerably. Various local bands participated in several large-scale attacks against at least a dozen farms, two rectories, one hermitage, one monastery, and one church. As in the early 1740s, a haphazard outing not authorized by the leaders and carried out toward the end of 1770 led to the discovery and subsequent demise of the robber bands.

In the early stages of the Bokkerijder movement—if that is an adequate description of these sustained forms of brigandage—most of the robbers came from the easternmost enclaves of the Austrian Netherlands and the adjoining reaches of the duchy of Gulick. With the towns of Nieuwstadt and Heerlen, the Dutch territories were only modestly represented at that time. Later, large groups of people from neighboring Dutch districts joined in the raids, while certain Austrian territories and the land of Gulick stopped being important areas of recruitment. All attacks took place late in the evening or in the early morning. During these nightly ventures the robbers looked for money, jewelry, clothing, food, and other valuable goods. Victims were often maltreated (to make them talk first and to keep them quiet after), and a few of them lost their lives. But not all operations involved the same amount of violence, nor were they all equally successful. Several important outings failed—some because the victims or their neighbors managed to give the alarm; others because the robbers found only items of little value. And it is significant that on a number of occasions, most notably during the large-scale operations in 1770, the victims were conspicuously spared, if they woke up at all.

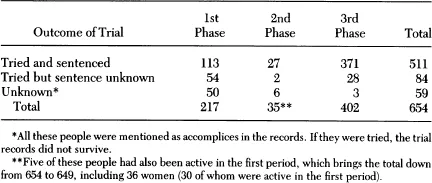

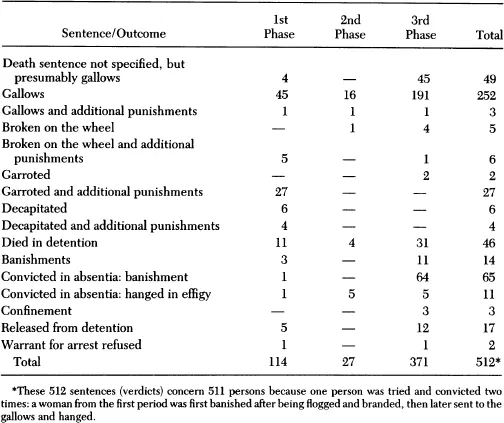

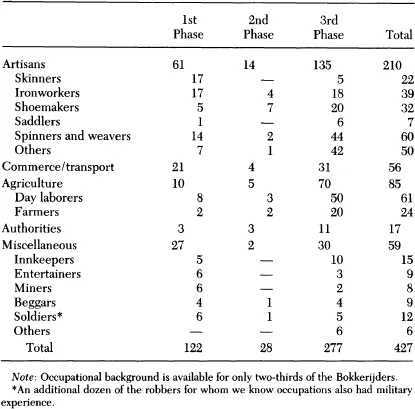

How many people actually participated in the operations of the robber bands we cannot possibly know. What we do know is that about 600 people were tried for being members of the “notorious band.” In the early 1740s, about 170 people (including well over 20 women) appeared before local courts. About ten years later, 29 people were tried, including 5 men who had also been active in the first period. During the trials of the 1770s, close to 400 people (6 of them women) were convicted (see Table 1.1), so I could trace more than 500 verdicts—which were all carried out. Most of these convictions involved death sentences. No less than 354 Bokkerijders were put to death one way or another (see Table 1.2). In most cases these executions took place near the robbers’ home towns. Relatively few convicted robbers—12 after being flogged, and 2 after being flogged and branded—were banished (they were mostly women and young men). For lack of sufficient proof, 17 suspects were released from detention. Only 3 people were sent to houses of correction. As many as 46 died in prison; in most cases we know the circumstances under which they expired, partly because they can be read from the sentences that the local courts passed on their remains. Finally, because many suspects had fled before the trials got under way, at least 76 people were tried in absentia. (The actual number was probably over 100; we know of an additional 34 fugitives under trial for whom no sentences could be traced.) Most of the fugitives were banished, and we know that at least 11 of them were hanged in effigy (Table 1.2). In order to understand the particulars of all these sentences, we have to know what these people were punished for and what might have brought them to take the road of brigandage.

Table 1.1. Number of Bokkerijders Brought to Trail. 1741–1778

Table 1.2. Outcome of Trials against Bokkerijders, 1741–1778

The collective biography of the Bokkerijders, which I compiled from the surviving court records and a few contemporary publications, reveals that these robbers were not bandits—that is, “outlaws”—in the strict sense of the word. On the contrary, virtually all of them led ordinary lives in their home towns. Most of the Bokkerijders were married and had children and a fixed residence. In fact, many were born and bred in the same area in which they carried out their raids—the east bank of the Lower Meuse. Some of the robbers even lived in the same village as their victims, and a few of them were close neighbors of the victims. This familiarity with victims and targets may explain the various forms of disguise that the robbers adopted. As mentioned before, they operated by night (hence one of their nicknames, nachtdieven—literally, night thieves). We know that the women used to dress as men, while the men often wore military attire and, to further hide their identity, made use of military idiom. Others blackened their faces and put on visors, wigs, false beards, caps, and other outlandish headgear. It should not surprise us, then, that the robbers fled when seen or caught in the very act of stealing. As local people, they had good reason to fear recognition. Thus, the Bokkerijders were far from being outlaws, vagrants, roaming beggars, or disbanded soldiers, although several had belonged to some of these categories at one time or another. Yet their military disguise as well as their relationship with an itinerant or peripatetic way of life are of fundamental importance for understanding the history of these bands.

Looking at the occupational background of the Bokkerijders, which I could trace for two-thirds of them, one finds artisans and retail merchants (peddlers, carters) strongly represented. Together they made up about 60 percent of the participants in all three stages of band operations, while farmers and day laborers accounted for scarcely 20 percent. For a distinctly rural area, people of agrarian background were notably underrepresented in the bands (see Table 1.3). Among the artisans, the skinners especially loomed large, most notably in the first phase. In fact, the first robber bands coalesced around a widely extended network of skinners—people whose job it was to kill sick animals, to dispose of dead cattle, to flay horses, and to remove other offal and remains. Skinners also assisted the executioner; they did the dirty work, such as dragging dead bodies of convicts from the prison to the gallows, where they had to hang them in chains or bury their remains.

Table 1.3. Occupational Background of Bokkerijders

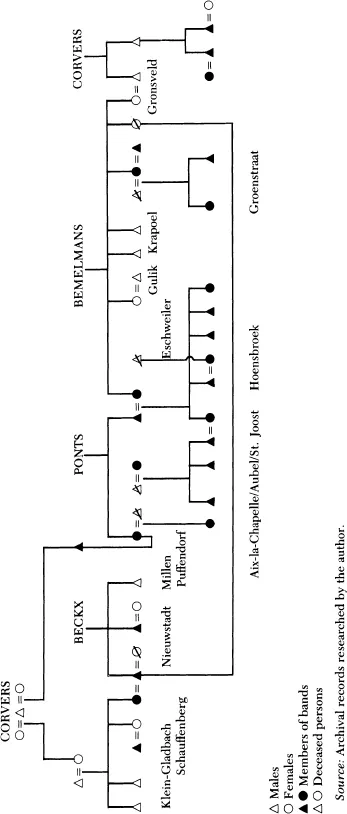

Together with some of their womenfolk, skinners from a dozen different villages and towns in the eastern Meuse valley (see Figure 1.1), were the main protagonists in the church robberies that were carried out in the early 1730s in at least twenty-five different locations. But the skinners also had an important part in the preparation and organization of the other raids in the first phase, while the division of the booty and sale of stolen goods (through Jewish receivers in the larger towns) was often in their hands.

The network of skinners was distinctly regional and endogamous. Like elsewhere, the endogamy of the skinners in the Lower Meuse resulted from the low value that the society put on their work (Wilbertz 1979; Blok 1981a, 1981b). Charged with the disposal of carrion and other refuse, their profession brought them into contact with dirt, with “matter out of place.” Hence they were stigmatized and placed at the margin of established society, which explains their low chances of marrying outside their occupational group. Nor could they easily enter into other occupations or crafts. Having their business at the edge of the village or in small rural hamlets near the larger settlements, the skinners were also marginal in a more literal sense—they were geographically and physically separated from the community they served. Because one family of skinners could provide for an entire rural community, the isolated positions of these craftsmen generated a far-flung, interlocal network of kin relations covering a large part of the eastern Meuse valley (see Figure 1.1 and Map 1).

Figure 1.1 Endogamous Network of Skinners in the Lower Meuse, 1730–1743

The skinners shared their low social status, peripheral location, and tactical mobility with other occupational groups that were strongly represented in the bands. We hear of peddlers, part-time beggars, musicians, jugglers, carters, innkeepers, and shoemakers. Although all these people had a fixed residence (and thus certainly did not belong to the fahrende Leute, or itinerant people), many of them moved a great deal between the vill...