eBook - ePub

In the Shadows of the American Century

The Rise and Decline of US Global Power

Alfred W. McCoy

This is a test

Share book

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

In the Shadows of the American Century

The Rise and Decline of US Global Power

Alfred W. McCoy

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In a completely original analysis, McCoy explores America’s rise as a world power, from the 1890s through the Cold War and its bid to extend its hegemony deep into the twenty-first century through a fusion of cyberwar, space warfare, trade pacts, and military alliances. McCoy then analyzes the marquee instruments of American hegemony—covert intervention, client elites, psychological torture, and worldwide surveillance.

Alfred W. McCoy’s 2009 book Policing America’s Empire won the Kahin Prize from the Association for Asian Studies.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is In the Shadows of the American Century an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access In the Shadows of the American Century by Alfred W. McCoy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Nordamerikanische Geschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

GeschichteSubtopic

Nordamerikanische GeschichtePART I

Understanding the US Empire

Chapter One

The World Island and the Rise of America

For even the greatest of empires, geography is often destiny. You wouldn’t know it in Washington, though. America’s political, national security, and foreign policy elites continue to ignore the basics of geopolitics that have shaped the fate of world empires for the past five hundred years. As a result, they have missed the significance of the rapid global changes in Eurasia that are in the process of undermining the grand strategy for world dominion that Washington has pursued these past seven decades.

A glance at what passes for insider “wisdom” in Washington reveals a worldview of stunning insularity. As an example, take Harvard political scientist Joseph Nye Jr., known for his concept of “soft power.” Offering a simple list of ways in which he believes US military, economic, and cultural power remains singular and superior, he argued in 2015 that there is no force, internal or global, capable of eclipsing America’s future as the world’s premier power. For those pointing to Beijing’s surging economy and proclaiming this “the Chinese century,” Nye offered up a roster of negatives: China’s per capita income “will take decades to catch up (if ever)” with America’s; it has myopically “focused its policies primarily on its region”; and it has “not developed any significant capabilities for global force projection.” Above all, Nye claimed, China suffers “geopolitical disadvantages in the internal Asian balance of power, compared to America.” Or put it this way (and in this Nye is typical of a whole world of Washington thinking): with more allies, ships, fighters, missiles, money, and blockbuster movies than any other power, Washington wins. Hands down.1

If Nye paints power by the numbers, former secretary of state and national security adviser Henry Kissinger’s latest tome, modestly titled World Order and hailed in reviews as nothing less than a revelation, adopts a Nietzschean perspective. The ageless Kissinger portrays global politics as highly susceptible to shaping by great leaders with a will to power. By this measure, in the tradition of master European diplomats Charles de Talleyrand and Prince Metternich, President Theodore Roosevelt was a bold visionary who launched “an American role in managing the Asia-Pacific equilibrium.” On the other hand, Woodrow Wilson’s idealistic dream of national self-determination rendered him geopolitically inept, just as Franklin Roosevelt’s vision of a humane world blinded him to Stalin’s steely “global strategy.” Harry Truman, in contrast, overcame national ambivalence to commit “America to the shaping of a new international order,” a policy wisely followed by the next twelve presidents. Among the most “courageous” of them was that leader of “dignity and conviction,” George W. Bush, whose resolute bid for the “transformation of Iraq from among the Middle East’s most repressive states to a multiparty democracy” would have succeeded, had it not been for the “ruthless” subversion of his work by Syria and Iran. In such a view, geopolitics has no place. Diplomacy is the work solely of “statesmen”—whether kings, presidents, or prime ministers.2

And perhaps that’s a comforting perspective in Washington at a moment when America’s hegemony is visibly crumbling amid a tectonic shift in global power. With its anointed seers remarkably obtuse on the subject of global political power, perhaps it’s time to get back to basics, to return, that is, to the foundational text of modern geopolitics, which remains an indispensable guide even though it was published in an obscure British geography journal well over a century ago.

Halford Mackinder Invents Geopolitics

On a cold London evening in January 1904, Halford Mackinder, the director of the London School of Economics, “entranced” an audience at the Royal Geographical Society on Savile Row with a paper boldly titled “The Geographical Pivot of History.” His talk evinced, said the society’s president, “a brilliancy of description … we have seldom had equaled in this room.”3

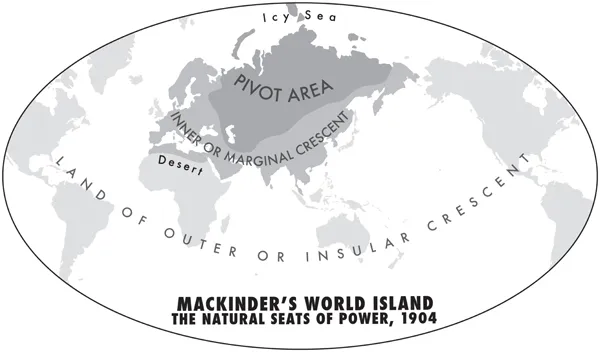

Mackinder argued that the future of global power lay not, as most British then imagined, in controlling the planet’s sea lanes but instead inside a vast landmass he called “Euro-Asia.” He presented Africa, Asia, and Europe not as three separate continents, but as a unitary landform, a veritable “world island.” Its broad, deep “heartland”—4,000 miles from the Persian Gulf to the Siberian Sea—was so vast that it could only be controlled from its “rimlands” in Eastern Europe or what he called its maritime “marginal” in the surrounding seas.4

The “discovery of the Cape road to the Indies” around Africa in the sixteenth century, Mackinder explained, “endowed Christendom with the widest possible mobility of power … wrapping her influence round the Euro-Asiatic land-power which had hitherto threatened her very existence.”5 This greater mobility, he later explained, gave Europe’s seamen “superiority for some four centuries over the landsmen of Africa and Asia.”6

Yet the “heartland” of this vast landmass, a “pivot area” stretching from the Persian Gulf across Russia’s vast steppes and Siberian forests, remained nothing less than the Archimedean fulcrum for future world power. “Who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island,” Mackinder later wrote. “Who rules the World-Island commands the world.” Beyond the vast mass of that island, which made up nearly 60 percent of the Earth’s landmass, lay a less consequential hemisphere covered with broad oceans and a few outlying “smaller islands.” He meant, of course, Australia, Greenland, and the Americas.7

For an earlier generation of the Victorian age, the opening of the Suez Canal and the advent of steam shipping had, he said, “increased the mobility of sea-power relatively to land power.” But now railways could “work the greater wonder in the steppe”—a reference to a historic event that everyone in his audience that night knew well: the relentless advance of the Trans-Siberian Railroad’s track from Moscow toward Vladivostok and the Pacific Ocean. Such transcontinental railroads would, he believed, eventually undercut the cost of sea transport and shift the locus of geopolitical power inland. In the fullness of time, the “pivot state” of Russia might, in alliance with another land power like Germany, expand “over the marginal lands of Euro-Asia,” allowing “the use of vast continental resources for fleet-building, and the empire of the world would be in sight.”8

For the next two hours, as he read through a text thick with the convoluted syntax and classical references expected of a former Oxford don, his audience knew that they were privy to something extraordinary. Several stayed after his talk to offer extended commentaries. The renowned military analyst Spenser Wilkinson, the first to hold a chair in military history at Oxford, pronounced himself unconvinced about “the modern expansion of Russia,” insisting that British and Japanese naval power would continue the historic function of holding “the balance between the divided forces … on the continental area.”9

Pressed by his learned listeners to consider other facts or factors, including the newly invented “air as a means of locomotion,” Mackinder responded: “My aim is not to predict a great future for this or that country, but to make a geographical formula into which you could fit any political balance.” Instead of specific events, Mackinder was reaching for a general theory about the causal connection between geography and global power. “The future of the world,” he insisted, “depends on the maintenance of [a] balance of power” between sea powers such as Britain or Japan operating from the maritime marginal and “the expansive internal forces” within the Euro-Asian heartland they were intent on containing.10

For publication in the Geographical Journal later that year, Mackinder redrew and even reconceptualized the world map by turning the globe toward Eurasia and then tilting it northward a bit beyond Mercator’s equatorial projection. Not only did this rendering show Africa, Asia, and Europe as that massive, unitary “world island,” but it also shrank Greenland and the Americas into inconsequential marginalia.11 For Europeans, used to projections that placed their continent at the world’s center, Mackinder’s map was an innovation; but for Americans, whose big, brightly colored schoolroom maps fostered an illusory sense of their hemisphere’s centrality by splitting the Eurasian landmass into two lesser blobs, it should have been a revelation.12

Apart from articulating a worldview that would influence Britain’s foreign policy for several decades, Mackinder also created, in that single, seminal lecture, the modern science of “geopolitics”—the study of how geography can, under certain circumstances, shape the destiny of whole peoples, nations, and empires.13

That night in London was, of course, more than a hundred years ago. It was another age. England was still mourning the death of Queen Victoria. Teddy Roosevelt was America’s president. The bloody, protracted American pacification of its Philippine colony was finally winding down. Henry Ford had just opened a small auto plant in Detroit to make his Model A, an automobile with a top speed of twenty-eight miles per hour. Only a month earlier, the Wright brothers’ Flyer had taken to the air for the first time—120 feet of air, to be exact.

Yet, for the next 110 years, Sir Halford Mackinder’s words would offer a prism of exceptional precision when it came to understanding the often obscure geopolitics driving the world’s major conflicts—two world wars, a Cold War, America’s Asian wars (Korea and Vietnam), two Persian Gulf wars, and even the endless pacification of Afghanistan. The question we now need to consider is this: How can Mackinder help us understand not only centuries past but also the half century still to come?

Britannia Rules the Waves

In the age of sea power that lasted just over four hundred years—from Portugal’s conquest of Malacca in 1511 to the Washington Disarmament Conference of 1922—the great powers competed to control the Eurasian world island via the sea lanes that stretched for 15,000 miles from London to Tokyo. The instrument of power was, of course, the ship—first, caravels and men-of-war, then battleships, submarines, and aircraft carriers. While land armies slogged through the mud of Manchuria or France in battles with mind-numbing casualties, imperial navies skimmed the seas, maneuvering for the control of coasts and continents.

At the peak of its imperial power around 1900, Great Britain ruled the waves with a fleet of three hundred capital ships and thirty naval bastions—fortified bases that ringed the world island from the North Atlantic at Scapa Flow off Scotland through the Mediterranean at Malta and Suez to Bombay, Singapore, and Hong Kong. Just as the Roman Empire had once enclosed the Mediterranean, making it mare nostrum (“our sea”), so British power would make the Indian Ocean its own “closed sea,” securing its flanks with army forts along India’s North-West Frontier and barring both Persians and Ottomans from building naval bases on the Persian Gulf.

By that maneuver, Britain also secured control over Arabia and Mesopotamia, strategic terrain that Mackinder had termed “the passage-land from Europe to the Indies” and the gateway to the world island’s “heartland.” From this geopolitical perspective, the nineteenth century was, in essence, a strategic rivalry, often called “the Great Game,” between Russia “in command of nearly the whole of the Heartland … knocking at the landward gates of the Indies,” and Britain “advancing inland from the sea gates of India to meet the menace from the northwest.” In other words, Mackinder concluded, “the final geographical realities” of the modern age were land power versus sea power.14

Intense rivalries, first between England and France, then England and Germany, helped drive a relentless European naval arms race that raised the price of sea power to nearly unsustainable levels. In 1805, Admiral Nelson’s flagship, the HMS Victory, with its oaken hull weighing just 3,500 tons, sailed into the battle of Trafalgar against Napoleon’s navy at nine knots, its hundred smoothbore cannon firing 42-pound balls at a range of no more than 400 yards.

Just a century later in 1906, Britain launched the world’s first battleship, the HMS Dreadnought, its foot-thick steel hull weighing 20,000 tons, its steam turbines allowing speeds of 21 knots, and its mechanized 12-inch guns rapid-firing 850-pound shells up to 12 miles. The cost for this Leviathan was £1.8 million, equivalent to nearly $300 million today. Within a decade, half-a-dozen powers had emptied their treasuries to build whole fleets of these lethal, lavishly expensive battleships.

Thanks to a combination of technological superiority, global reach, and naval alliances with the United States and Japan, a Pax Britannica would last a full century, 1815 to 1914. In the end, however, this global system was marked by an accelerating naval arms race, volatile great-power diplomacy, and a bitter competition for overseas empire that imploded into the mindless slaughter of World War I, leaving sixteen million dead by 1918.

As the eminent imperial historian Paul Kennedy once observed, “The rest of the twentieth century bore witness to Mackinder’s thesis,” with two world wars fought over “rimlands” running from Eastern Europe to East Asia.15 Indeed, World War I was, as Mackinder himself later observed, “a straight duel between land-power and sea-power.”16 At war’s end in 1918, the sea powers—Britain, America, and Japan—sent naval expeditions to Arkhangelsk, the Black Sea, and Siberia to contain Russia’s revolution inside its own “heartland.”

During World War II, Mackinder’s ideas shaped the course of the war beyond anything he could have imagined. Reflecting Mackinder’s influence on geopolitical thinking in Germany, Adolf Hitler would risk his Reich in a misbegotten effort to capture the Russian heartland as lebensraum, or living space, for his German “master race.”

In the interwar years, Sir Halford’s work had influenced the ideas of German geographer Karl Haushofer, founder of the journal Zeitschrift für Geopolitik and the leading proponent of lebensraum. After retiring from the Bavarian Army as a major general in 1919, Haushofer studied geography with an eye to preventing a recurrence of the strategic blunders that had contributed to Germany’s defeat in World War I. Later, he would become a professor at Munich University, an adviser to Adolf Hitler, and a “close collaborator” with deputy führer Rudolf Hess, his former student. Through his forty books, four hundred articles, countless lectures, and frequent meetings with top Nazi officials including Hitler, Haushofer propagated his concept of lebensraum, arguing that “space is not only the vehicle of power … it is power.” His teaching inspired what an investigator for the Nuremburg war crimes tribunal called “visions of German...