- 242 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

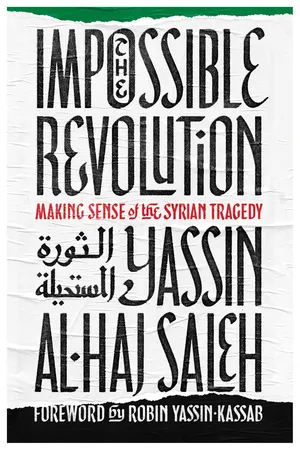

Impossible Revolution

About this book

Syria's dictator Bashar al-Assad and his junta regime have slaughtered hundreds of thousands of Syrians in the name of fighting terrorism. Former political prisoner, and current refugee, Yassin al-Haj Saleh exposes the lies that enable Assad to continue on his reign of terror as well as the complicity of both Russia and the US in atrocities endured by Syrians.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

REVOLUTION OF THE COMMON PEOPLE

DAMASCUS, JUNE 2011

For hundreds of thousands of Syrians, the Syrian popular uprising has been an extraordinary experience, ethically and politically: an experience of self-renewal and social change, an uprising to change ourselves and a revolution to change reality.

1

The young and the elderly, women and men, are changing their lives and renewing themselves through their participation in the protest movement, bravely facing arrest, torture, or death. After confronting danger face to face, they have emerged stronger and more courageous, more dignified and more open. Such an experience is not available to those who refrain from participating in the protests, nor has a similar experience on such a large scale been possible for about two generations of Syrians. Through their engagement in a costly, collective venture, these renewed Syrians have developed a hitherto unmatched spirit of selflessness and lively solidarity. Out of desperation (in the literal sense of the word—which in Arabic, as istimata, denotes putting your life into your struggle, risking death to achieve your purpose) for a more common purpose, Syrians who are participating in the uprising have been freed of both fear and selfishness. The always edgy and dangerous and often catastrophic and tragic nature of these experiences guarantees that they will remain in the national memory for generations to come.

It is appropriate to speak in terms of a revolution because many Syrians are radically changing themselves while struggling to change their country and emancipate their fellow Syrians. For that reason in particular, it will be very difficult to defeat the uprising.

Over the past forty years, the regime has imposed a narrow and impoverished existence on Syrians, lives devoid of new experiences, rejuvenation, and passion. We have lived ‘material’ lives in every sense of the word, deprived of any moral, ethical, spiritual, and aesthetic dimensions; purely worldly lives to the point of abject cynicism, in the context of which religion might have seemed the sole spiritual confection to be found in an arid desert.

Today, the uprising provides bountiful new experiences for a large number of Syrians. The voluntary and emancipatory nature of this extraordinary experience renders it a democratic uprising. It is unprecedented under the Assadist regime.

2

Thanks to the communications revolution (and modern cell phone technology in particular), the distance between field activity and media coverage has shrunk considerably, allowing for more democratic forms of organization and leadership to emerge within the movement. Widely supported by modern means of communication (specifically cell phones, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube videos) and the instantaneous delivery of news and images to TV channels, new technologies have filled the gaps that resulted from news correspondents being prevented from working in Syria.

Each activist, young ones in particular, is making a new reality in multiple ways. By taking to the streets in defiance of a tyrannical power that has come to represent the past, and working to change it, and then again through documentation, he or she creates a new reality and ensures that it becomes known and tangible by broadcasting it across public media outlets. Such actions provide (relative) protection for the movement, allowing it to address public opinion in the country and in the world, gaining the sympathy of broad segments of Syrians, Arabs, and people further afield. If it were not for this vital ‘central nervous system’ (i.e., the young men and women who cover their own activities on-site) the uprising would be isolated, and much easier for the regime to destroy.

Moreover, the activities of those armed with a cell phone camera create an objective memory of the uprising, and build an enormous audio-visual archive. This archive is made up of the efforts of thousands of Syrians, and is being watched by millions of Syrians everywhere, which provides additional immunity from oblivion. Verbal testimony is fragile compared to photography; the latter is also more likely to persist in collective memory. Both cell phones and Facebook have played roles in differentiating and individualizing independent contributors. New media have also played an expanded role in democratizing participation in the production of information, and in the creation of a different public space, a ‘virtual’ arena that is impenetrable by authorities. New technologies are playing a communicative role in the creation of new and resilient communities working against the regime, in addition to their role in building a memory of the uprising by keeping an immense record of all its minutiae, day by day and area by area.

Besides the visual archive, there is also a large and growing number of stories written and posted online by direct participants. These narratives will find their way into the public sphere one day.

In addition to assembling a memory that is resistant to confiscation and erasure, the process of photo-documentation of the uprising has allowed for a decisive victory in the media battle. The regime possesses nothing that even remotely resembles the credibility, dynamism, and broad-based coverage of the uprising’s documents, which were compiled at nearly no financial cost. The human cost, however, has been very high.

This new reality forged by activists has also reinforced the moral superiority of the intifada. Those who sacrifice their freedom and risk their lives to cover their uprising stand in stark contrast with the ‘Party of the Couch’, to borrow a term used by Egyptian activists during their revolution (i.e. those who follow the revolution on TV). Still less can those who sacrifice their freedom and risk their lives be compared with the regime’s ideologists and journalists, its apologists and shabiha (thugs), its tools of oppression or its murderers, junior and senior.

The courage, sacrifice, and collective spirit that characterize the uprising are certain to eventually constitute a national experience, one that will make a contribution to the reconstruction of the country.

This is to say that a regime capable of engaging in a war against the rebellion of the governed is entirely incapable of fighting a war against their memories. The regime may be able to overcome the intifada by force, but such a victory will only mark the first round in a longer struggle, one in which Syrians will already have recourse to a sophisticated memory of exceptional experiences, a source of support for them in any future rounds of their liberation struggle.

3

Today, there are two powers in Syria: the regime and the popular uprising.

The regime possesses arms, money, and intimidation. The regime kills, but is devoid of meaning or substance. The uprising, on the other hand, has had to meet the challenge of overcoming fear and is consequently infused with the spirit of freedom.

The uprising is the embodiment of selflessness, which amounts to sacrificing life, whereas the regime is the embodiment of selfishness, which amounts to the destruction of the country for the survival of an intellectually, politically, and ethically degenerate junta. The uprising is an ethical and political rebellion, and the most positively transformative event in the history of modern Syria since independence. But the regime has turned on Syrians, because it can only thrive over a meek, divided, and unconscious body politic.

The uprising allows for personal identities, while the regime invalidates all names save for the one it has imposed on everything in the country: ‘Assad’. Streets, squares, the largest lake, hospitals, the largest library, are all named after Assad; even the country itself is known as ‘Assad’s Syria’. The uprising revives the original names of places: in Daraa Governorate: Jasim, Nawa, Bosra, Da‘el, Inkhil; in Damascus: Kanaker, Douma, Harasta, al-Midan, Barza, Rukned-Din, Moadamiyeh, al-Tal, al-Kiswah, Qatana, Jdeidat Artouz; in Homs: Bab al-Sebaa, Bab Dreeb, al-Waer, al-Rastan, Talbiseh, al-Qusayr; in Hama: al-Hader, al-Souq, al-Assi Square, al-Salamiyah; in Idlib: Maarrat al-Nu‘man, Jisr al-Shughour, Kafranbel, Binnish, Khirbat al-Jawz, Mount Zawiya; in Aleppo: the University, Sayfed-Dawla, Salah ed-Din, as-Sakhour, Ainal-Arab, Tall Rifaat, Manbij, al-Bab; in al-Hasakah: al-Qamishli, Ras al-Ayn, Amuda, Derbassiyeh; in Latakia: al-Saliba, ar-Raml al-Falastini, al-Skantori, Jableh; in Tartus: Banias, Al-Bayda, Raqqa, and Tabaqa; in Deir ez-Zour: al-Mayadeen, al-Bukamal, and al-Ghourieh.

The uprising also gives names to Friday protests: The Good Friday (as a sign of respect to the Christian communities), Friday of Anger, Azadi (Freedom, in Kurdish) Friday, Saleh al-Ali Friday (named after an Alawi leader of resistance against the French in early 1920s), and Irhal (leave) Friday, among many others. The uprising is freeing the country’s name from its shackles. It is ‘Syria,’ not ‘Assad’s Syria’, nor is it the ‘State of the Baath.’

Through its revival of names, the uprising has been creating personalities, i.e. active centres for initiatives and free will. By contrast, the regime was established upon the idea of turning Syria and all Syrians into the subjects of a single free agent: ‘The Assad Self.’

The uprising reveals the stifled richness of Syria: the social, cultural, and political richness of Syria and its damaged population, those whom the hand of tyranny has long alienated or excluded. The uprising has given them a stage for speaking in public upon which they can cheer, object, satirize, chant or sing: they can occupy the public sphere and liberate it from totalitarian control.

Through the revival of individualizing names, the uprising also makes it possible for Syrians to regain control of their lives and their environments by telling their stories and repairing their language, opening it up to some of their most vivid emotions.

4

The ‘modernization and development’ policies attributed to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad were superficial makeovers at the material level of tools and devices (modern cars, malls and restaurants, lavish hotels and bank branches, ‘Ivy League’ schools, etc.). They were devoid of any humane, ethical, or political essence. Values such as political rights, public freedoms, social solidarity, and cultural progress all remained unheard of. In fact, social and national solidarity declined significantly among Syrians, and the humanitarian and emancipatory dimensions of culture deteriorated beneath the cliquish, intolerant ideologies perpetuated by ideologues of ‘modernity’.

The real identity of the regime consists of the combination of an obsolete, inhumane political apparatus with a glamorous material façade. This makes for more than just an authoritarian political system: it is a social, political, and ideological system based on racial discrimination with respect to the population, as well as holding a monopoly on power, wealth, and patriotism. This supercharged monopoly is one of the reasons for the popular protests, which perhaps explains why the protests began in Syria’s hinterland and ‘peripheral’ towns. The ongoing economic liberalization in Syria spurred a model of development that favoured cities at the expense of rural areas, city centres at the expense of outlying neighbourhoods, and wealthy modern suburbs at the expense of the crowded traditional suburbs where those excluded by the neoliberal authoritarian development model found a last refuge. These areas have all been marginalized, and unemployment levels have soared due to the requirements asked of prospective employees within the new labour market (proficiency in foreign languages and familiarity with new technologies, to name but a few). At the same time, there has been a decline in the social role of the state, with government representatives transformed into a rich elite, ruling the locals with scorn and disdain as if they themselves were foreign dignitaries. The president’s cousin, Atef Najib, arrested and tortured children in Daraa before the outbreak of the uprising and then suggested to their parents that they just forget their children, telling the fathers that he and his men will impregnate their wives if they failed to do so. This is an example of a powerful, brutish, affluent, and savage man who enjoys absolute immunity.

Syrians have seethed under these developments, which have also provoked new levels of contempt and psychological detachment. And although these developments are not entirely new, during recent years they have brought about degrees of social and cultural segregation equivalent to apartheid.

Intellectuals have contributed to the institutionalization of these social conditions by propagating an authoritarian form of secularism, one obsessed with monitoring the role of religion in public life while entirely ignoring the roles played by the political system and power elites. This aristocratic and dishonest form of secularism has justified the regime’s heavy-handed mechanism of political governance: it has reduced the intellectual and moral fortifications that protect the lives of the general public; and it has joined with a racist international cultural and political climate (as Benedict Anderson has explained, racism is an ideology of class, not an ideology of identity). This secularism contributed to legitimating the transfer of power, concentrating it in the hands of those that rule in Syria today. Atef Najib did not emerge from the doctrines of the likes of Adonis, George Tarabichi, or Aziz al-Azmeh (three well known Syrian secularist intellectuals), but this dogma strongly reduced the intellectual, moral, and symbolic barriers that would have prevented him from emerging, along with other, similar monsters.

To sum up, one can say that the Syrian revolution erupted against a form of modernization that was merely economic liberalization caterin...

Table of contents

- The Impossible Revolution

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword by Robin Yassin-Kassab

- Introduction

- 1. Revolution of the Common People

- 2. The Shabiha and their State

- 3. The Danger of a ‘State of Nature’

- 4. Arms and the Revolution

- 5. The Roots of Syrian Fascism

- 6. The Rise of Militant Nihilism

- 7. ‘Assad or No One’

- 8. An Image, Two Flags, and a Banner

- 9. The Destiny of the Syrian Revolution

- 10. The Neo-Sultanic State

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Impossible Revolution by Yassin al-Haj Saleh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Genocide & War Crimes. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.