- 504 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

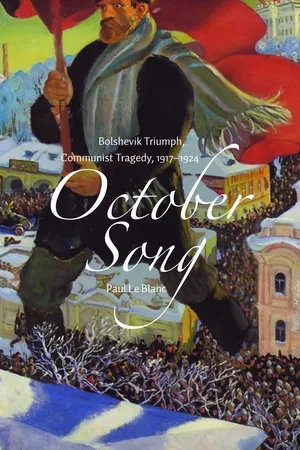

October Song

About this book

A panoramic account of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and its aftermath – animated by the lives, ideas and experiences of workers, peasants, intellectuals, artists, and revolutionaries of diverse persuasions – October Song vividly narrates the triumphs of those who struggled for a new society and created a revolutionary workers state. Yet despite profoundly democratic and humanistic aspirations, the revolution is eventually defeated by violence and authoritarianism.

October Song highlights both positive and negative lessons of this historic struggle for human liberation.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Nothing Can Ever Be the Same

An arduous voyage in 1917 brought four close friends, idealistic young journalists from the United States, to the shores of Russia. In the midst of an immensely destructive world war, the centuries-old tyranny of monarchist autocracy had been overthrown. The revolutionary process was continuing, and the four wanted to understand what was going on.

The revolution began with International Women’s Day rallies on March 8 (February 23 according to the old tsarist calendar) that got out of hand. They sparked momentous insurgencies among the common working people of Petrograd, with the military’s rank and file refusing to repress the people’s uprising and instead joining it. Masses of workers and soldiers (the latter mostly peasants in uniform) organized a growing and increasingly substantial network of democratic councils—the Russian word was soviety (or soviets)—to coordinate their efforts. In addition to liberty (indicated by freedom of speech and organization, equal rights for all, the right of workers to form trade unions, and so forth), they demanded peace and bread as well as land for the country’s impoverished peasant majority. In the wake of the monarchy’s sudden collapse, conservative, liberal, and moderate socialist politicians scurried to form a provisional government that would contain the revolutionary process and consider how “best” to address the demands for peace, bread, land. The most militant faction of the Russian socialist movement—the Bolsheviks (majority-ites) led by Vladimir Ilyich Lenin—insisted that peace, bread, and land would only be achieved by overthrowing the provisional government and giving all political power to the soviets. This, they believed, would spark a world process of workers’ revolutions that would end war and imperialism, overturning all tyrannies and bringing a transition from capitalism to socialism. After several months of intensive activity and experience, the Bolsheviks and their allies won majorities in the soviets and went on to make the second revolution of 1917—a popularly supported insurrection on November 7 (October 25 according to the old calendar).

One of the eyewitnesses, John Reed, cabled the news back to the United States: “The rank and file of the Workmen’s, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Councils are in control, with Lenin and Trotsky leading. Their program is to give the land to the peasants, to socialize natural resources and industry and for an armistice and democratic peace conference. . . . No one is with the Bolsheviki except the proletariat, but that is solidly with them. All the bourgeoisie and appendages are relentlessly hostile.”1

The first of the four friends to get their books out (in October 1918) were Louise Bryant and Bessie Beatty. After ten decades, the freshness of their astute observations and vibrant impressions continues to reward the reader.

With Six Months in Red Russia, Louise Bryant is visibly wrestling toward an understanding of the vast and complex swirl of experience. “I who saw the dawn of a new world can only present my fragmentary and scattered evidence to you with a good deal of awe,” she tells us. “I feel as one who went forth to gather pebbles and found pearls.” Reaching for generalization, she writes: “The great war could not leave an unchanged world in its wake—certain movements of society were bound to be pushed forward, others retarded. . . . Socialism is here, whether we like it or not—just as woman suffrage is here, and it spreads with the years. In Russia the socialist state is an accomplished fact.”2

“Revolution is the blind protest of the mass against their own ignorant state,” writes her friend Bessie Beatty in The Red Heart of Russia. “It is as important to Time as the first awkward struggle of the amoeba. It is man in the act of making himself.” Obviously still trying to comprehend what she had seen, she muses: “Time will give to the world war, the political revolution, and the social revolution their true values. We cannot do it. We are too close to the facts to see the truth.” But she immediately adds: “To have failed to see the hope in the Russian Revolution is to be a blind man looking at the sun rise.”3

The last of the books to appear (in 1921), Albert Rhys Williams’s Through the Russian Revolution, reaches for the interplay of cause and effect, of objective and subjective factors:

It was not the revolutionists who made the Russian Revolution. . . . For a century gifted men and women of Russia had been agitated over the cruel oppression of the people. So they became agitators. . . . But the people did not rise. . . . Then came the supreme agitator—Hunger. Hunger, rising out of economic collapse and war, goaded the sluggish masses into action. Moving out against the old worm-eaten structure they brought it down. . . . The revolutionists, however, had their part. They did not make the Revolution. But they made the Revolution a success. By their efforts they had prepared a body of men and women with minds trained to see facts, with a program to fit the facts and with fighting energy to drive it thru.4

The “middle” book of the four—appearing on January 1919—was the one destined to become the classic eyewitness account, John Reed’s magnificent Ten Days That Shook the World. A fierce partisan of the Bolsheviks, he quickly joined the world Communist movement that the Bolsheviks established in the same year that his book was published. But no one of any political persuasion can disagree with the generalization that appears in the book’s preface: “No matter what one thinks of Bolshevism, it is undeniable that the Russian Revolution is one of the great events of human history, and the rise of the Bolsheviki a phenomenon of worldwide importance.”5

In more than one sense, these friends continue to reach out to us. Of course, they offer their own lived experience and eyewitness impressions of what happened in one of the great events in human history. But also, while they and all they knew have long since died, the patterns and dynamics and urgent issues of their own time have in multiple ways continued down through history, to our own time. The experience, ideas, and urgent questions they wrestle with continue to have resonance and relevance for many of us today, and this will most likely be the case for others tomorrow.

Corroboration and Contrasts

In the 1930s three particularly significant accounts of the revolution appeared. Leon Trotsky’s three-volume History of the Russian Revolution, released in 1932–33, was followed by William H. Chamberlin’s two-volume The Russian Revolution, 1917–1921—both published outside of the Soviet Union. From within the USSR, in 1938, came the most authoritative account, embedded in the seventh chapter of History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): Short Course—composed by a commission of that organization’s Central Committee, with the very active participation of Joseph Stalin.

“Trotsky’s writing was absorbing, and the translator, Max Eastman . . . did him justice,” recalled Carl Marzani, one of many radicalizing intellectuals in the United States during the 1930s. “The details, from the revolutionary insider, were fascinating, but the volume excited me most as a sample of Marxist writing and methodology. Trotsky set the revolution within a historical context, and treated the Tsarist Empire as a whole, a society rich with contradictions.” High praise indeed from someone who would soon become a Communist Party organizer in the Age of Stalin. More recently, the decidedly non-Trotskyist scholar Ian Thatcher has chimed in: “Trotsky’s summary of the factors he had highlighted to account for 1917 still forms the research agenda. . . . Measured against The History of the Russian Revolution most ‘modern’ research does not seem so modern after all. . . . It is essential reading.” Chamberlin, a highly respected correspondent of the Christian Science Monitor with twelve years of journalistic experience in Soviet Russia, was evolving from radical supporter to conservative critic of the Soviet regime, but he sought to provide a balanced account that later scholars have viewed—in the recent words of Sheila Fitzpatrick—as “still the best general work on the Revolution and Civil War.” Both Trotsky’s and Chamberlin’s accounts drew from primary source materials and reminiscences of participants, and both were consistent with what John Reed, Louise Bryant, Albert Rhys Williams, and Bessie Beatty had reported years before.6

In stark contrast, the account from Stalin and his collaborators contained major elements that were missing from the accounts of the four American friends. While none of them had even mentioned Stalin, the Short Course volume reported that in 1917, Lenin was especially reliant on “his close colleagues and disciples in Petrograd: Stalin, Sverdlov, Molotov, Ordjonikidze,” and that the Bolshevik Central Committee “elected a Party Centre, headed by Comrade Stalin, to direct the uprising.” More than this, it was claimed that people they had seen as among Lenin’s closest comrades were in fact his enemies, and that “the Bolsheviks defeated the attempts of the capitulators within the Party—

Zinoviev, Kamenev, Rykov, Bukharin, Trotsky and Pyatakov—to deflect that Party from the path of Socialist revolution.” In the same period, General Secretary of the Communist International Georgi Dimitrov explained to Communists and others throughout the world the need to “enlighten the masses . . . in a genuinely Marxist, a Leninist-Marxist, a Leninist-Stalinist spirit,” mobilizing “international proletarian unity . . . against the Trotskyite agents of fascism,” and recognizing that a “historical dividing line” in world politics was represented by one’s “attitude to the Soviet Union, which has been carrying on a real existence for twenty years already, with its untiring struggle against enemies, with its dictatorship of the working class and the Stalin Constitution, with the leading role of the Party of Lenin and Stalin.” The Short Course was designed to facilitate this task.7

Zinoviev, Kamenev, Rykov, Bukharin, Trotsky and Pyatakov—to deflect that Party from the path of Socialist revolution.” In the same period, General Secretary of the Communist International Georgi Dimitrov explained to Communists and others throughout the world the need to “enlighten the masses . . . in a genuinely Marxist, a Leninist-Marxist, a Leninist-Stalinist spirit,” mobilizing “international proletarian unity . . . against the Trotskyite agents of fascism,” and recognizing that a “historical dividing line” in world politics was represented by one’s “attitude to the Soviet Union, which has been carrying on a real existence for twenty years already, with its untiring struggle against enemies, with its dictatorship of the working class and the Stalin Constitution, with the leading role of the Party of Lenin and Stalin.” The Short Course was designed to facilitate this task.7

No less divergent from the early accounts of John Reed and his friends, and similarly inclined to stress the unity of Lenin and Stalin, were a proliferation of works from the late 1940s to the 1960s by Cold War anti-Communist scholars. A bitter ex-Communist working for the US Department of State, Bertram Wolfe, pioneered a distinctive development of the continuity thesis. “When Stalin died in 1953, Bolshevism was fifty years old. Its distinctive views on the significance of organization, of centralization and of the guardianship or dictatorship of a vanguard or elite date from Lenin’s programmatic writings of 1902,” Wolfe wrote. “His separate machine and his authoritarian control of it dates from . . . 1903.” In that half-century, Wolfe insisted, “Bolshevism had had only two authoritative leaders”: Lenin and Stalin. There were many who followed this lead. “Stalinism can and must be defined as a pattern of thought and action that flows directly from Leninism,” asserted Alfred G. Meyer. “Stalin’s way of looking at the contemporary world, his professed aims, the decisions he made at variance with one another, his conceptions of the tasks facing the communist state—these and many specific traits are entirely Leninist.” Robert V. Daniels, contrasting “the Trotskyists” with “Stalin and more direct followers of Lenin,” elaborated: “Leninism begat Stalinism in two decisive respects: it prepared a group of people ready to use force and authority to overcome any obstacles, and it trained them to accept any practical short-cut in the interest of immediate success and security of the movement.” W. W. Rostow agreed: “Lenin decided . . . to rule on the basis o...

Table of contents

- October Song

- Preface

- 1. Nothing Can Ever Be the Same

- 2. Prerevolutionary Russia

- 3. Revolutionary Triumph

- 4. Proletarian Rule and Mixed Economy

- 5. Global Context

- 6. Losing Balance

- 7. Majority of the People

- 8. Liberty under the Soviets

- 9. Consolidation of the Soviet Republic

- 10. Inevitabilities and Otherwise

- Methodological Appendix

- Bibliography

- Notes

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access October Song by Paul Le Blanc, Paul Le Blanc in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.