![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The End of Cheap Energy

Our prosperity and way of life are sustained by energy use. [E]nergy security must be a priority of US trade and foreign policy.

— National energy policy; The Cheney Report, May 2001

America faces a major energy supply crisis over the next two decades. The failure to meet this challenge will threaten our nation’s economic prosperity, compromise our national security, and literally alter the way we lead our lives.— Secretary of Energy Spencer Abraham, National Energy Summit, March 19, 2001.

When Mike Bowlin, Chairman of ARCO, said in 1999 that “We’ve embarked on the beginning of the last days of the age of oil,” he was voicing a truth that many others in the petroleum industry knew but dared not utter. Over the past few years, evidence has mounted that global oil production is nearing its historic peak.

Oil has been the cheapest and most convenient energy resource ever discovered by humans. During the past two centuries, people in industrial nations accustomed themselves to a regime in which more fossil-fuel energy was available each year, and the global population grew quickly to take advantage of this energy windfall. Industrial nations also came to rely on an economic system built on the assumption that growth is normal and necessary, and that it can go on forever.

However, that assumption is set to come crashing down. The evidence that oil is about to become less abundant is accumulating quickly.

The oil business started in America in the late nineteenth century, and the US became the most-explored region on the planet — more oil wells have been drilled in the lower-48 states than in all other countries combined. Thus, America’s experience with oil will eventually be repeated elsewhere.

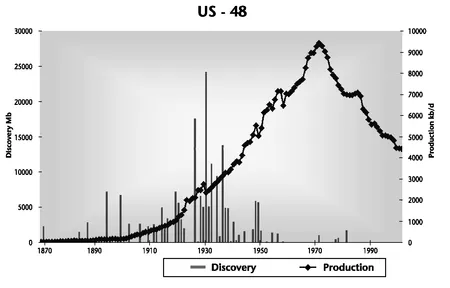

Oil discovery in the US peaked in the 1930s; US oil production peaked roughly forty years later. Since 1970, the US has had to import increasing amounts of oil nearly every year in order to make up for its shortfall from domestic extraction.

Figure 1: The US Discovery and Depletion Profile The US discovery and depletion profile.

(Source: Colin Campbell)

dp n="32" folio="19" ?Global discovery of oil peaked in the 1960s. Since production must eventually mirror discovery, global oil production will doubtless peak at some point in the foreseeable future. When, exactly? According to many informed estimates, the peak will occur between 2006 and 2016.

When the global peak in oil production is reached, there will still be plenty of petroleum in the ground — about as much as has been extracted up to the present, or roughly one trillion barrels. But much of the remaining oil will be of lower quality, or more difficult and expensive to access. As a result, every year from then on it will be impossible to pump as much as the year before.

Clearly, we will need to find substitutes for oil. But an analysis of the currently available energy alternatives is not reassuring.

The extraction rate of natural gas will peak globally only a few years after that of liquid petroleum (natural gas production in North America is already falling rapidly, as we will see later in this chapter).

Coal seems relatively abundant until one looks closely: much of what is in the ground is of low quality or will be difficult to extract. The energy profit ratio for coal — the amount of energy it yields minus the amount expended in obtaining the resource — has been falling rapidly over the past decades. If we rely on coal to make up shortfalls from other fossil fuels, extraction rates will peak within decades.1

Solar photovoltaics (PV) and wind power are renewable, and production capacity is capable of being greatly expanded (which is not the case with our primary renewable energy source, hydroelectric power). However, we now get only a small fraction of one percent of our national energy budget from them; extremely rapid growth will be necessary if they are to replace even a significant fraction of the energy shortfall from post-peak oil.

Nuclear power is dogged by the unsolved problem of radioactive waste disposal, as well as fears about accidents, terrorism, and diversion of fuels or wastes to weapons programs. To make up for fossil fuel depletion, we would eventually need hundreds of new nuclear plants, and the necessary uranium would run out within just a few decades.

dp n="33" folio="20" ?Hydrogen is not an energy source at all, but an energy carrier: it takes more energy to produce a given quantity of hydrogen than the hydrogen itself will yield. Moreover, most commercially produced hydrogen now comes from natural gas — whose global production will peak only a few years after oil begins its historic decline.

Unconventional petroleum resources — so-called “heavy oil,” “oil sands,” and “shale oil” — are plentiful but extremely costly to extract and process, a fact that no technical innovation is likely to change much (we will discuss hydrogen and unconventional hydrocarbon resources in more detail in Chapter 4).

There are many more possible energy sources for the future — some of them quite promising. But none in sight even comes close to matching the cheapness and convenience of oil during its heyday: after all, nature took millions of years to create petroleum; all we had to do was to extract and burn it. Fossil fuels are the equivalent of a huge inheritance — one that we have spent quickly and not too wisely. Other energy sources will be more analogous to wages: we will have to work for what we get, and our spending will be restricted to immediate income. The hard math of energy resource analysis yields an uncomfortable but unavoidable prospect: even if efforts are intensified now to switch to alternative energy sources, after the global oil peak industrial nations will have less energy available to do useful work — including the manufacturing and transporting of goods, the growing of food, and the heating of homes.

To be sure, we should be investing in alternatives and converting our industrial infrastructure to use them. If there is any solution to industrial societies’ approaching energy crises, renewables plus conservation will provide it. Yet in order to achieve a smooth transition from non-renewables to renewables, decades will be needed — and we do not have decades before the peak in the extraction rate of oil occurs. Moreover, even in the best case, the transition will require the massive shifting of investment from other sectors of the economy (such as the military) toward energy research and conservation. And the available alternatives will likely be unable to support the kinds of transportation, food, and dwelling infrastructure we now have; thus the transition will entail an almost complete redesign of industrial societies.

The likely economic consequences of the coming energy transition will be enormous. All human activities require energy — which physicists define as “the capacity to do work.” With less energy available, less work can be done — unless the efficiency of the process of converting energy to work is raised at the same rate as energy availability declines. It will therefore be essential, over the next few decades, for all economic processes to be made more energy-efficient. However, efforts to improve efficiency are subject to diminishing returns, and so eventually a point will be reached where reduced energy availability will translate to reduced economic activity. Given the fact that our national economy is based on the assumption that economic activity must grow perpetually, the result is likely to be a recession with no bottom and no end.

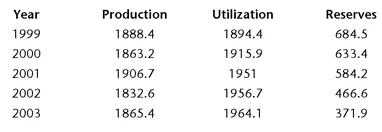

THE PEAK IN PER-CAPITA GLOBAL GRAIN PRODUCTION? Data for world cereal crops in million tons:

(Source: Food and Agriculture Organization)

Grains constitute 80 to 90 percent of world food supply. In each of the past five years, consumption has outstripped production, and shortfalls have been made up for by the drawing down of reserves. With this year’s draw-down, world grain stocks have dropped to the lowest level since the early 1970s, when world prices of wheat and rice doubled as a result. If the recent pace of draw-downs is projected into the future, world grain reserves will be exhausted in the year 2008.

dp n="35" folio="22" ?The consequences for global food production will be no less dire. Throughout the 20th century, food production expanded dramatically in country after country, with most of this growth attributable to energy inputs. Without fuel-fed tractors and petroleum-based fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides, it is doubtful that crop yields can be maintained at current levels.

The oil peak will also impact international relations. Most of the wars of the twentieth century were fought over resources — in many cases, oil. But those wars took place during a period of expanding resource extraction; the coming decades of heightened competition for dwindling energy resources will likely see even more frequent and deadly conflicts. The US — as the world’s largest energy consumer, the center of the global industrial empire, and the holder of the most powerful store of weaponry in world history — will play a pivotal role in shaping the geopolitics of the new century. To many observers, it appears that oil interests are already at the heart of the present administration’s geopolitical strategy.

There is much that individuals and communities can do to prepare for the energy crunch. Anything that promotes individual self-reliance (gardening, energy conservation, and voluntary simplicity) will help. But the strategy of individualist survivalism will offer only temporary and uncertain refuge during the energy downslope. True individual and family security will come only with community solidarity and interdependence. Living in a community that is weathering the downslope well will enhance personal chances of surviving and prospering far more than will individual efforts at stockpiling tools or growing food.

Meanwhile, nations must adopt radical energy conservation measures, invest in renewable energy research, support sustainable local food systems instead of giant biotech agribusiness, adopt no-growth economic and population policies, and strive for international resource cooperation agreements.

These suggestions describe a fundamental change of direction for industrial societies — from the larger, faster, and more centralized to the smaller, slower, and more locally-based; from competition to cooperation; and from boundless growth to self-limitation.

dp n="36" folio="23" ?If such recommendations were taken seriously, they could lead to a world a century from now with fewer people using less energy per capita, all of it from renewable sources, while enjoying a quality of life perhaps enviable by the typical industrial urbanite of today. Human inventiveness could be put to the task, not of making ways to use more resources, but of expanding artistic satisfaction, finding just and convivial social arrangements, and deepening the spiritual experience of being human. Living in smaller communities, people would enjoy having more control over their lives. Traveling less, they would have more of a sense of rootedness, and more of a feeling of being at home in the natural world. Renewable energy sources would provide some conveniences, but not nearly on the scale of fossil-fueled industrialism. This will not, however, be an automatic outcome of the energy decline. Such a happy result can only come about through sustained, coordinated, and strenuous effort.

There are a few hopeful indications that a shift toward sustainability is beginning. But there are also discouraging signs that large political and economic institutions will resist change in that direction. Thus, the most likely trajectory for the energy transition will consist of the collapse of industrial civilization as we know it, probably occurring in stages over a period of several decades. Whether that collapse occurs in a chaotic or controlled way, and whether the generations following the collapse will face bleak or favorable prospects, will depend upon choices we make now.

Recent Confirmations of an Imminent Oil Peak

Confirmation of an imminent oil peak was, in brief, the substance of my previous book, The Party’s Over. At the time of the book’s publication, this was a highly controversial message. Much of it is far less so today.

What has changed? The idea that a geologically-based peak in the rate of global oil extraction is imminent has entered mainstream discussion. The following are a few of the more significant signs that this notion — though still obscure to the average citizen — is not only gaining increasing confirmation from experts, but is becoming a matter of common knowledge among the well-informed.

In an article titled “A Revolutionary Transformation” in

The Lamp, a quarterly published for ExxonMobil shareholders published in September 2003, exploration division president Jon Thompson reflected on the dramatic changes in exploration technology over the past 40 years and the challenges that lie ahead in finding and producing future supplies of oil and gas. “[W]e estimate that world oil and gas production from existing fields is declining at an average rate of about four to six percent a year,” he wrote.

To meet projected demand in 2015, the industry will have to add about 100 million oil-equivalent barrels a day of new production. That’s equal to about 80 percent of today’s production level. In other words, by 2015, we will need to find, develop and produce a volume of new oil and gas that is equal to 8 out of every 10 barrels being produced today. In addition, the cost associated with providing this additional oil and gas is expected to be considerably more than what industry is now spending.2

Thompson’s statements were regarded by many industry insiders as an oblique admission that it will soon be virtually impossible for production levels to keep up with demand.

The reason for Thompson’s pessimism could be discerned in facts elucidated in an article by Richard C. Duncan of the Institute on Energy and Man in Seattle, titled “Three World Oil Forecasts Predict Peak Oil Production,” published in the May 26, 2003 issue of Oil and Gas Journal. Duncan noted that “Forecasts of the imminent depletion of oil are as old as the industry itself, and that has not changed. What has changed is the growing amount of historical oil data now available to test forecasts.”3 Of the 44 significant oil-producing nations, at least 24 are clearly past their peak of production, according to Duncan. Thus, the discussion about an approaching global oil production peak is ever less about prognostication, and more about s...