![]()

Part One

Introducing Senior Cohousing

Imagine a living arrangement in which multiple, individually owned housing units (usually 20-30) are oriented around a common open area and a common house — aplace where community is a way of life. Imagine residents who actively cooperate in planning the project with one goal in mind — to recreate an old-fashioned neighborhood that supports friendly cooperation, socialization, and mutual support. Imagine senior cohousing.

dp n="25" folio="6" ?dp n="26" folio="7" ? ![]()

CHAPTER 1

Taking Charge of the Rest of Your Life

Some years ago I lost my husband and went through a difficult time. But I am glad that I lived here when it happened since it meant that I never felt unsafe. I was not together with other residents all the time, but I knew they were there for me if I needed them. And when I came home at night I could feel the warmth approach me as I drove up our driveway.

— Møllebjerg in Korsør, Denmark

So many American seniors live in places that do not accommodate their most basic needs. In the typical suburb, the automobile is a de facto extension of the single-family house. Driving is an absolute requirement for a person wanting to conduct business, shop, or participate in social activities. As we get older, as our bodies and minds age, the activities we once took for granted aren’t so easy anymore: the house becomes too big to maintain; a visit to the grocery store or doctor’s office becomes a major expedition; and the list goes on. Of course many, if not most, seniors recognize the need to take control of their own housing situation as they age. They dream of living in an affordable, safe, readily accessible neighborhood where people of all ages know and help each other. But then what? What safe, affordable, neighborhood-oriented, readily accessible housing choices actually exist?

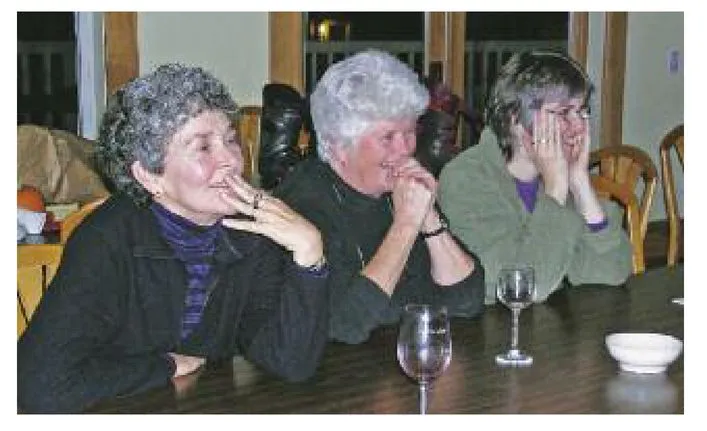

Conversation after dinner at Bellingham Cohousing, Bellingham, Washington.

dp n="27" folio="8" ? The author and his mother, Rosemary.

The modern single-family detached home, which constitutes about 67 percent of the American housing stock, is designed for the mythical nuclear family consisting of a working father, a stay-at-home mother, and two point four children. Today, less than 25 percent of the American population lives in such households. Almost 25 percent of the population lives alone, and this percentage is increasing as the number of Americans over the age of 60 increases. At the same time, the surge in housing costs and the increasing mobility of the population combine to break down traditional community ties. And, for the first time in the history of the US more women live without husbands than with.

Meeting the Kristensens

When Katie and I were in Denmark in 1984-85 researching our first book about cohousing, we interviewed a couple who was planning one of the first senior cohousing communities there.

I met Mr. Kristensen, a 67-year-old retired high school principal, at a planning meeting for his new cohousing community, Abildgården. We discussed not only the common elements of Abildgården, the cozy common library, the bright and airy dining room they planned, but also the open floor plan of his own new house in the cohousing community, in which the kitchen, dining, and living areas were part of the same space but distinct at the same time. The “overlapping” would allow the smaller spaces to appear larger, and at the same time would create opportunities that larger, closed off spaces wouldn’t.

After the meeting, we drove to his current house and parked out front. As we walked to the front door Mr. Kristensen mentioned that this 2,900-square-foot house was now too big for them.

In the house, I was impressed by the turn-of-the-century china cabinet, the stately dining table, the highboy, and the grandfather clock. They would never be able to get all this into their new 1,000 sq. ft. cohousing unit. “How can you leave all of this?” I gasped, involuntarily. “Sell it, give it to the kids,” Mr. Kristensen exclaimed (he’d been asked this question before, I thought).

“We’ve made up our minds (without regrets), and there’s no looking back,” Mrs. Kristensen (65) interjected. We’ll sell the house and most of the furniture that we’ve collected over the last 40 years, and our parents collected 40 years before that.”

“We’ll keep what’s meaningful, but we’ll sell the rest and one of our cars, and we’ll travel around the world. Abildgården will be finished just in time for our return.”

“Our life’s role won’t be reduced to being curators or caretakers of things until we can no longer do that,” Mr. Kristensen continued. “We’re going to be a part of something that’s more interesting than this furniture. There, our house will be part of a neighborhood, and ‘life’s maintenance’ will be half the trouble — not by paying someone else to take care of us, but by cooperating with the neighbors. We’ll have more time to live. After discussing every detail of the plans, we feel like Abildgården is ours; we built it, not brick by brick, but discussion by discussion. It will be worth more to us.” Mrs. Kristensen continued, “Statistically, one of us will die in the next ten years. Then, statistically, the other will remain in this big house for another ten years, increasingly dependent on our children and the government. Then one day, the children will become impatient with having to be with one of us for our birthday, Christmas, Easter, Mother’s Day, whatever, and they’ll find a more institutional setting for us where we’ll have ‘company, support, and attention,’ but it won’t necessarily be what we want. And by that time, we’ll be too weak and tired of burdening our children to object to whatever they come up with. And we’ll live out our lives there, dependent and unhappy. Instead, we want to stay independent for as long as possible. And we want to be in control of our future and our lifestyle. We believe that by helping to create it now, we’ll have the community we need to rely on for support, and not rely on institutional care.”

Well, the Kristensens’ project wasn’t done when they returned — they never seem to be finished quite on time — but they have enjoyed what appears to be the independence with intradependence goal that they were seeking.

Currently, seniors represent a record 12.4 percent of the American population, which, with the swell of post-WWII baby boomers entering seniorhood, will increase to 20 percent by the year 2030. Clearly, action must be taken, and quickly, to correct these household and community shortcomings. But what can be done, and by whom? How can we better house ourselves as we age?

I believe that the answer lies in senior cohousing communities. Having visited many of these communities, I’m now a firm believer that 20 seniors stranded on a desert island would do better at taking care of most of their basic needs than the same 20 left isolated or in an institution.

Typical senior housing. Expensive, but no one wants to be here.

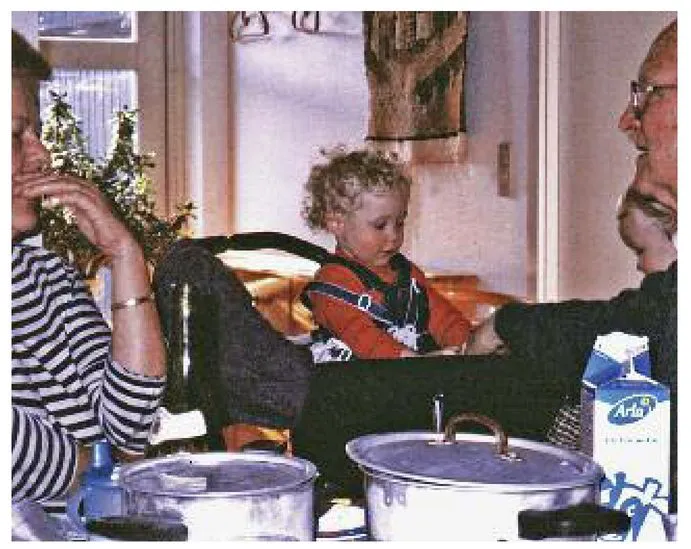

dp n="29" folio="10" ? “Why would I want to live in senior cohousing — wouldn’t it be better to live in mixed-age cohousing?” is a relevant question. Neither choice is better; it’s a personal decision. But it’s amazing how often young people are hanging around in senior cohousing. Kids visiting, grandkids visiting, neighbors visiting. And it’s a more fun place to hang around for them than typical senior or assisted living facilities.

Searching for a Solution

When I was in Denmark a couple of years ago to further study senior cohousing, I was there, admittedly, for somewhat selfish reasons. The agonies of placing my own mother in an assisted-living facility were still fresh. Her story is, unfortunately, typically American: at 72 years old and determinedly, but detrimentally, living alone, she could no longer competently care for herself. Her children, doing their best, had reached the limits of their competency. Institutionalized assisted care, and eventually nursing care, were her only options. Or were they?

With my mother needing immediate care, she moved into the most agreeable facility we could find and afford. In the meantime, we continued to search for institutional care for her that was not an institution. But what we found was a business system designed to care for people, not with people. The most agreeable senior living facilities can be so large and impersonal that even a well-meaning staff of caregivers cannot truly care about their clients; moreover, institutional, language, and cultural barriers often create a palpable distance between client and staff. Although they may be competent in their care-giving skills, staff are often young and speak English as a second language. Many seniors, for a wide variety of health and cultural reasons, have great difficulty communicating with them. This, of course, does not endear the staff to the clients; and the staff, in turn, can have little patience with this often-cranky elderly population.

Institutionalized American seniors also bear a heavy economic burden as they age. Skilled nursing and convalescent care costs much more than in-home care, and competent in-home care is expensive, starting at about $6,500 a month in California. That nest egg goes all too quickly. Worse, before the disabled elderly can collect medical benefits, they must spend down all of their assets. The result is that the elderly who have the audacity to linger too long have little or no wealth to support themselves with or to leave behind.

After 20 years of designing, building, and living the cohousing life in the US, I was certain there had to be a better way for seniors, too.

A Danish Solution Again

In Denmark, people frustrated by the available housing options developed cohousing: a housing type that redefined the concept of neighborhood to fit contemporary lifestyles. Tired of the isolation and the imp...