![]()

CHAPTER 1

An Introduction to Solar Electricity

Like many other people throughout the world, I have been dreaming of a future powered by renewable energy for many years. Fortunately, that dream is becoming a reality. Today, solar and wind energy have become major contributors to global energy production. In the United States alone, solar, wind (mostly large-scale wind), biomass, and geothermal now produce about 7% of the nation’s electricity. When you add hydroelectricity to the mix, renewable energy now supplies over 13% of America’s electricity. That’s a recent change, occurring within the last few years. Although we have a ways to go, that’s pretty amazing.

What is even more amazing is that some states now generate about 25% of their electricity from renewables. Kansas and Iowa, for example, both do, mostly with wind power. Colorado generates 18% of its electricity from renewables, but its goal is 30% by 2020. California is aiming for 33% by 2020. While impressive, get this: Germany now produces over 60% of its electricity from renewables.

Although there are many reasons why renewables have gone wild in recent years, one of them has been cost. For years, renewable energy advocates have dreamed of a day when we could say that renewables cost the same or less than conventional energy resources. At least for solar electricity, those days are here. Solar electric systems, even without subsidies, often produce electricity at or below the cost of power from utilities. They have reached price parity, and the future is looking quite bright.

This book focuses on an important element of the renewable energy dream: solar electricity. Solar electric systems are also known as photovoltaic systems or PV systems, for short. In this book, I will focus primarily on residential-scale PV systems, that is, systems suitable for homes and small businesses. These systems generally fall in the range of 1,000 watts for very small, energy-efficient cabins or cottages to 5,000 to 15,000 watts for typical suburban homes. All-electric homes could require even larger systems, on the order of 25,000 watts. What does all this mean?

Understanding Rated Power

One of the most frequent questions solar installers are asked is “What size system do I need?” It’s probably the question that’s burning in your mind right now.

The answer is almost always the same: it depends. More specifically, it depends on how much electricity you and your family use. Once an installer knows how much electricity you consume, he or she can size a system.

The size of a solar electric system is given in its rated power, also known as rated capacity. Rated power of a system is the output of the modules (PV panels) times the number of modules. If your system contains twenty 250-watt modules, its rated capacity is 5,000 watts. Because kilo means 1,000, a 5,000-watt system is also called a 5-kilowatt, or 5-kW system. But what does it mean when I say a module’s rated power is 250 watts?

Rated power is the instantaneous output of a solar module measured in watts under standard test conditions (STC). Watts is a measure of power. Another way of thinking about it is as the rate of the flow of energy. The higher the wattage, the greater the flow.

Watts is also the measurement used to rate technologies that produce electricity, such as a solar module or a power plant. For example, most solar modules installed these days are rated at 250 to 300 watts. Power plants are rated in millions of watts, or megawatts: a typical coal-fired power plant produces 500 to 1,000 megawatts of power.

Most readers are probably more familiar with the terms watt and wattage when they are used to rate power consumption of a device, such as a light bulb or a hair dryer. You may have a 12-watt compact fluorescent light bulb, for instance, or an 1,800-watt hair dryer. Your microwave may be 1,200 watts. In such cases, wattage indicates power consumption. The higher the wattage, the greater the consumption.

As just noted, the rated output of a PV module is determined under standard test conditions—a set of conditions that all manufacturers use to rate their modules. To test a module, workers set it up in a room that is maintained at 77°F (25°C). A light is flashed on the module at an intensity of 1,000 watts per square meter. That is equivalent to full sun on a cloudless day in most parts of the United States. The light is arranged so light rays strike the module at a 90° angle, that is, perpendicularly. (Light rays striking the module perpendicular to its surface result in the greatest absorption of the light.)

Rating modules under standard test conditions is useful for comparing one manufacturer’s module to another’s. A 285-watt module from company A should perform the same as a 285-watt module from company B.

Installers can use this rating to determine the size of a system required to meet your needs. As noted above, most residential solar electric systems fall within the range of 5,000 to 15,000 watts, or 5 to 15 kW. It is important to note, however, that a 5-kW PV system won’t produce 5,000 watts of electricity all the time the Sun’s shining on it. This rating is based on standard test conditions, which are rarely duplicated in the real world. So, this rating system leaves a bit to be desired.

When mounted outdoors, PV modules typically operate at higher temperatures than those subjected to standard test conditions. That’s because infrared radiation in sunlight striking PV modules causes them to heat up. To achieve a cell temperature of 77°F (25°C) under full sun, like that measured in the laboratory, the air temperature must be quite low—about 23°F to 32°F (0°C to −5°C), not a typical temperature for PV modules in most locations most of the year. This is important to know because higher temperatures decrease the output of a solar module. That’s the reason why it is so important to mount a solar system so that the modules stay as cool as possible. It also explains why solar modules on a ground-mounted rack typically perform better than roof-mounted systems. Roofs are hotter.

To better simulate real-world conditions, the solar industry has developed an alternative rating system. They call it PTC, which stands for PV-USA Test Conditions (which stands for PV for Utility-Scale Applications Test Conditions).

PTC were developed at the PV-USA test site in Davis, California, and more closely approximate real-life operating conditions. In this rating system, the ambient temperature is held at 68°F (20°C). The modules face the Sun and output is measured when the Sun’s irradiance reaches 1,000 watts per square meter. The conditions take into account higher module temperatures and the cooling effect of wind. Wind speed in the test is 2.24 miles per hour (or 1 meter per second) 10 meters above the surface of the ground. (That is, wind speed is monitored at 10 meters, or 33 feet.) Although the cell temperature varies with different modules, it is typically about 113°F (45°C) under PTC. Because power output (in watts) decreases with rising temperature, PTC ratings are roughly 10% lower than STC ratings.

When shopping for PV modules, I used to suggest that readers ignore the nameplate rating the manufacturers derived under STC and look up the PTC ratings. Some manufacturers publish these data on their spec sheets; others don’t. As a rule, though, it’s not that important. Solar installers will estimate the output of an array taking into account local conditions. If you must, you can find PTC ratings on the California Energy Commission’s website: consumerenergycenter.org.

An Overview of Solar Systems

As their name implies, solar electric systems convert sunlight energy into electricity. This conversion takes place in the solar modules, more commonly referred to as solar panels. (The term modules is the correct one; that’s what they are called in the National Electric Code, but few people use this term.)

FIGURE 1.1. These solar modules being installed by several students at The Evergreen Institute consist of numerous square solar cells. Each solar cell has a voltage of around 0.6 volts. The cells are wired in series to produce higher voltage, which helps move the electrons from cell to cell. Modules are also wired in series to increase voltage. Credit: Dan Chiras.

A solar module consists of numerous solar cells. Most solar modules contain 60 solar cells, although manufacturers are also producing larger modules that contain 72 cells each. Solar cells are made from one of the most abundant chemical substances on Earth, silicon dioxide. (Silicon dioxide makes up 26% of the Earth’s crust.) Silicon dioxide is found in quartz and from a type of sand that contains quartz particles. Silicon is extracted from silicon dioxide.

Solar cells are wired in series inside a module (see sidebar). The modules are encased in glass (in the front) and usually plastic (in the back). The plastic and glass layers protect the solar cells from the elements, especially moisture. Most modules these days have aluminum frames. Because the anodized (silver) aluminum frames are striking, many manufacturers produce modules with black aluminum frames. The aluminum rails and mounting hardware used to attach them to the roof are also black, so the array blends in well, and homeowners associations and neighbors are happy. Some manufacturers are now producing frameless modules to make them even more aesthetically appealing. One manufacturer’s modules passed an unprecedented Class 4 hail testing (that is, they withstood 2-inch hail striking it at 75 mph), making them the most impact-resistant module in the industry. Frameless modules have been designed to make installation quick, easy, and less expensive.

Two or more modules are typically mounted on a rack and wired together. Together, the rack and solar modules are referred to as an array. Ground-mounted arrays are typically anchored to the earth by a steel-reinforced concrete foundation. Together, the rack, modules, and foundation are referred to as an array.

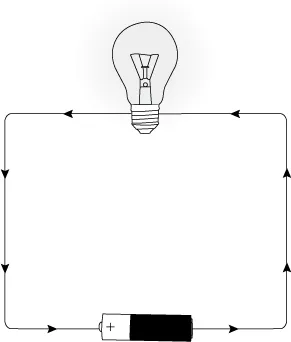

Solar modules produce direct current (DC) electricity. That’s one of two types of electricity in use today. It consists of a flow of tiny subatomic particles called electrons. They flow through conductors, usually copper wires. In direct current electricity, electrons flow in one direction, as illustrated in Figure 1.2. In this case, electrons flow out of the battery through the light bulb, where they give off their energy, creating light and heat. The de-energized electrons then flow back into the battery.

FIGURE 1.2. Solar electric systems produce direct current (DC) electricity just like batteries. As shown here, in DC circuits the electrons flow in one direction. The energy the electrons carry is used to power loads like light bulbs, heaters, and electronics. Credit: Forr...