eBook - ePub

Bastards of Utopia

Living Radical Politics after Socialism

Maple Razsa

This is a test

Share book

- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Bastards of Utopia

Living Radical Politics after Socialism

Maple Razsa

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Bastards of Utopia, the companion to a feature documentary film of the same name, explores the experiences and political imagination of young radical activists in the former Yugoslavia, participants in what they call alterglobalization or "globalization from below." Ethnographer Maple Razsa follows individual activists from the transnational protests against globalization of the early 2000s through the Occupy encampments. His portrayal of activism is both empathetic and unflinching—an engaged, elegant meditation on the struggle to re-imagine leftist politics and the power of a country's youth. More information on the film can be found at www.der.org/films/bastards-of-utopia.html.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Bastards of Utopia an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Bastards of Utopia by Maple Razsa in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Anarquismo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

AnarquismoCHAPTER ONE

GRASSROOTS GLOBALIZATION IN NATIONAL SOIL

A nation[al people] without a state is like a shit in the rain.

The most honest fucking statement I’ve heard about nationalism . . . from a fascist. What does that make the Croatian state? The roof they built over their shit? . . . And where does that leave me?

Every individual is compelled to find in the transformation of the imaginary of “his” or “her” people the means to leave it, in order to communicate with individuals of other peoples with which he or she shares . . . to some extent, the same future.

On May 2, and again on May 3, 1995, rebel ethnic Serbs fired surface-to-surface missiles at Zagreb. Loaded with antipersonnel cluster bombs, each missile showered more than a hundred thousand deadly steel pellets down on the city center of Croatia’s capital. Several hundred were injured and seven were killed (Hayden 2012:216–217).2 A crowded tram was struck only a hundred meters from Pero’s apartment. While Croatia underwent far-reaching social changes in the wake of state socialism’s demise—the wrenching “triple transition” (Offe 1991)—it is the “ethnic violence” that accompanied the transition to independent statehood for which the former Yugoslavia is known. Unlike the relatively peaceful dissolution of other multinational socialist states, like the Soviet Union3 or Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia was violently dismembered, and there was widespread targeting of civilians. A complete accounting of the historical conditions that made the wars of Yugoslav succession so bloody is beyond the scope of this book. Given how much of the organizing efforts of the alterglobalization movement were directed against the institutions of the Washington Consensus, it is worth noting the significant role of the IMF in the destruction of Yugoslavia. IMF-imposed structural adjustment policies in the 1980s precipitated the first conflicts between the republics of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), which emerged over assistance given by more developed republics like Slovenia and Croatia to less developed ones like Macedonia and Bosnia (Woodward 1995). One dynamic, however, charged the reciprocal violence that developed more than any other: competing efforts to found independent nation-states from multinational SFRY. Nationalists in each republic demanded what Thomas Hylland Eriksen has defined as the core belief of nationalism: that “political boundaries should be coterminous with cultural ones” (2010:131). Such demands, always intrinsically violent (Balibar 2002), were especially dangerous in the context of Yugoslavia’s remarkably heterogeneous ethnic composition. SFRY inherited kaleidoscopic maps of religious and cultural difference in many areas—legacies of the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires.

Paradoxically, it was the reciprocity of the hatred and violence that led many on the left to claim, as Pero often did, that the Serbian and Croatian nationalists were one another’s most essential political allies. This certainly appears to be the case for the respective wartime presidents of Serbia and Croatia, Slobodan Milošević and Franjo Tuđman. The victory of Franjo Tuđman and the HDZ in the first Croatian democratic elections in 1990 would have been unimaginable without the increasingly polarized atmosphere created by the threatening stance of the Slobodan Milošević regime in the neighboring republic of Serbia. Tuđman, with financial backing from extremist elements of the Croatian diaspora in Argentina, the United States, Australia, and especially Canada, promulgated a classically nationalist platform, arguing that multinational Yugoslavia—as a unified state for all South Slavs—was an unnatural imposition; Croatians must have their own state. The election of an avowed Croatian nationalist, who went so far as to claim that the fascist Ustaša regime, which had carried out genocidal policies against Serbs, Jews, Roma, and antifascist Croats during the short existence of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH—Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, 1941–1945) was not only a quisling state “but an expression of the political desires of the Croat nation for its own independent state” (Biondich 2004:70). Such statements allowed Milošević, in turn, to claim that Croatia was reviving Croatian fascism and that, therefore, minority Serbs were again in danger and only his strong hand could protect them. Eventually, the partnership in enmity between Milošević and Tuđman moved on to direct and secret agreement to divide the neighboring and ethnically mixed republic of Bosnia at the expense of its largest ethnic constituency: its Muslim population.

Immediately upon election, Tuđman set about realizing Croatians’ “millennial desire” for an independent Croatian state. The new constitution he promoted defined Croatia as the state of the Croatian nation (narod) (Hayden 2000). While there were still significant portions of the population that saw interethnic coexistence as possible—and preferable—these constituencies were successfully demobilized, intimidated, and silenced by the outbreak of armed conflict (Gagnon 2006), especially once the Serb-dominated Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) intervened militarily to support the seizure of one-third of Croatia’s territory by rebellious minority Serbs.4 By the time Croatia recaptured this territory in 1995—finally realizing the nationalist dream on the ground—Croatia’s political climate was overwhelmingly nationalist and xenophobic (Denich 1994; Hayden 1996) and alternatives had been effectively silenced (Gagnon 2006).5 Even in 2013, one would find wide swaths of the Croatian countryside pockmarked with the shells of Serb homes that were dynamited to ensure Serbs would never return to contested territory. The violent conflict in Croatia serves as an important historical backdrop for this book; it was also the formative political experience for Zagreb’s radical activists—including my three key collaborators—who all came of age during the war and its aftermath. To be sure, the war formed them differently than it did activists of an older generation, those who were involved with the Antiwar Movement of Croatia (cf. Bilić 2012), who generally had a more modest agenda, even a relatively depoliticized orientation, as becomes clear when I discuss intergenerational tensions on the left, especially during the campaign against the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq.

In the unlikely conditions of extreme ethnic polarization and hegemonic nationalism, activists in Croatia developed a small yet militant strain of antinationalist expression, initially from within the anarcho-punk subcultures in Pula, Rijeka, and especially Zagreb, sometimes intermingling with other spheres of activism, including antiwar activism and publishing.6 Incidents like the 1995 rocket attacks aside, Zagreb was spared the generalized shelling that cities like Vinkovci, Vukovar, Slavonski Brod, and Karlovac endured. Developing antinationalism in these cities would have been much more difficult because, as the anthropologist Tone Bringa has demonstrated in Bosnia, it is existential fear more than hatred that accounts for ethnic mobilization (2005:72). As her documentary “We Are All Neighbors” (Granada TV 2003) makes heartbreakingly clear, there is a tipping point beyond which—no matter how strongly one may have supported coexistence previously—one must align with one’s own co-nationals if one wants to survive. What is more, as a city of a million residents with the strongest subcultural and activist traditions in Croatia, Zagreb offered, relatively speaking, a hospitable social terrain for political alternatives.

Nonetheless, we should not underestimate how difficult it was in the face of the broader rightward turn in Croatian political culture for activists to develop and personally embody the oppositional practices and alternative desires of this committed antinationalist and antifascist youth culture. Their responses to the nation-state were not only reactive, however. Just as important as activists’ critical attitudes toward local nationalisms were the variety of proactively transnational collaborations in which they participated—their “globalization from below” (globalizacija odozdo). These collaborations in alternative publishing and electronic communications, self-education, music distribution and performance, protest organization, and video production afforded them a vivid sense of working to produce different values in themselves and others, of contributing to a global “culture of resistance,” and of belonging to a political community—the alterglobalization movement—that stretched far beyond Croatian territory. Antinationalists’ alliances, inclusive metaphors of collective action, and agonistic and participatory sense of do-it-yourself culture offer a stark contrast to the exclusionary, homogenous, and traditionalist cultural politics of nationalism. Aside from any political or theoretical contrast, their antinationalist subculture allowed activists to cultivate and sustain values fundamentally at odds with those of the broader society in which they lived.

Antifascist Action in Zagreb: January 12, 2002

Since beginning fieldwork eight months ago, I have regularly filmed activists’ public actions, but I have not proposed recording activists’ everyday lives—or their more furtive late-night “interventions.” In part I have hesitated to intrude with my camera on less public aspects of anarchist life for fear of inflaming suspicions that I am a spy. On the one hand, this distrust—usually raised half-jokingly or retroactively admitted by collaborators who said that they had initially feared I was a spy but now trust me—highlights the skepticism with which Americans are increasingly viewed as the contours of the Global War on Terror become clearer and the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq appears increasingly imminent. On the other hand, activists’ suspicions are evidence of the ways the close surveillance they face from Croatian security services, evident in Pero’s post-arrest interrogation, corrode trust and openness among movement participants.

This particular winter evening is different, however, because Pacho, with whom I co-produced an earlier documentary (Razsa and Velez 2002), is in Zagreb for a brief exploratory visit. He wants to see for himself if the local anarchist scene warrants the years of work another feature film will demand—plus Pero predicted a “night action” (noćna akcija), piquing Pacho’s interest. In the end no one objects to his request to film, so Pacho teases me that I have “gone native,” meaning that I have become unnecessarily paranoid “like Rimi.” He now shoots unobtrusively from the corner of Pero’s crowded living room, leaning lightly on a pile of silkscreen frames to stabilize his shot.

Seven activists from Antifašistička akcija (Antifascist Action or AFA), all men in their late teens to midtwenties, are sprawled on a foraged couch or hunkered down on the floor. Pero’s place, sometimes sardonically referred to as AFA “headquarters” (generalni štab)—or derisively as “the boys club” by some anarcha-feminists7—is where activists most often assemble antifascist zines, research, and graffiti stencils, and where they plan their sometimes more forceful actions against neofascist youth. Pero takes in the banter as he organizes a heap of papers, discarding old magazines and newspapers, filing activist publications, fliers, and press releases in AFA’s archive of heavy three-ring binders. His chunky dark-framed glasses, held together with electrical tape on one side, give him a look of disheveled yet thoughtful erudition. They belie his failure to finish secondary school and the glue sniffing of his hardest days living on the street. Perhaps giving this background too much weight, I am sometimes caught off guard by his subtle wit, keen sense of self-irony, and uncanny knowledge of Zagreb’s urban landscape. I never learn more about the city than when I walk the streets with Pero as he tears down announcements for religious meetings by the far-right priest Zlatko Sudac, narrates the history of neglected buildings, sabotages billboards he deems sexist, and recalls street fights with Zagreb’s football hooligans and skinheads.

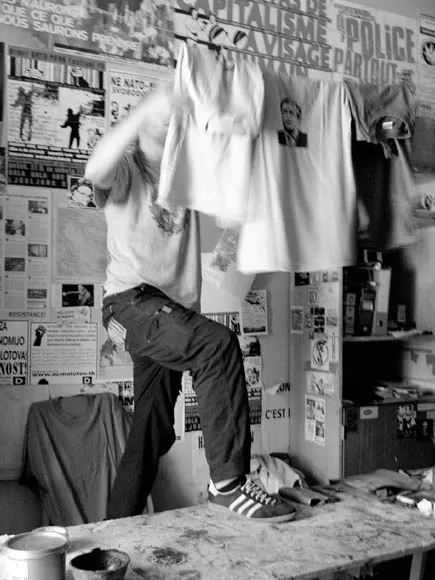

Figure 1.1. Rimi silkscreens anti-Bush T-shirts at Pero’s apartment. The history of recent European protests is chronicled in the posters papering the walls behind him. Photo by author.

Pero’s years on the street were not the result of a “broken” or abusive home life, as they are for many homeless youth. In fact, Pero is from a stable and relatively wealthy family. Politically and socially conservative, his parents own a successful wholesale ceramic tile firm. In his words, Pero broke off contact for several years beginning at age 15 “because of brutal political fights.” He was periodically homeless until a social worker intervened, convincing his parents to allow him to live here in the apartment of his recently deceased grandmother. He now sees his parents for occasional Sunday meals—where his strict vegetarianism is a constant source of conflict.

Vintage brass light fixtures aside, there are few signs that this was once an elderly grandmother’s apartment. The space has been “collectivized” and in its decoration—and cleanliness—it feels like many European squats. Radical posters paper the walls. Zines, fliers, CDs, patches, and T-shirts—the sale of which funds their activities—are stacked in every available space (see figure 1.1). While Pero cleans up, Marin and Ljubo debate whether or not to participate in this year’s Gay Pride Parade. AFA marched last year during the first Pride, when extreme right elements in the Catholic Church organized a counterdemonstration and successfully disrupted the parade. The howling-mad crowd first threw ashtrays and bottles from nearby cafes. Then two men hurled teargas canisters into the center of the Pride march, “in complete coordination with the police,” Rimi insists. With the Social Democrats now leading the ruling coalition in parliament, however, Pride will enjoy substantial police protection this year. Rimi, who is rolling another weak homegrown joint, looks up to declare that he “won’t be caught dead with police protection . . . They would rather beat us than the skins any day. They are just worried about their EU [membership] application.”8

While much of my attention in the field was drawn to activists’ innovative forms of direct action—actions that often generated dramatic clashes, like those with counterdemonstrators at Gay Pride—daily life with my collaborators was by no means always eventful. More often, days passed like this evening, revolving around socializing, chatting, hanging out, even explicitly wasting time together—sometimes referred to as čamanje, an “empty mood, the inability to escape boredom, a state without action” (Hrvatski enciklopedijski rječnik 2002). In other words, Pero’s prediction of a night action was many dawdling hours ago, and it is seeming increasingly unlikely that this night will generate anything very cinematic. By midnight, Pero is preparing a third round of Turkish coffee—which he insists on calling kafa, using the Serbian rather than the properly Croatian kava. In fact, those around AFA regularly use a self-conscious mix of Serbian, Bosnian, and Croatian rather than the officially promoted “pure Croatian.” Despite the coffee—and perhaps my very American impatience with inactivity9—I try to settle into the loose flow of čamanje. No sooner have I begun to relax, however, than I am caught off guard by an intense flurry of activity, as so often happens during fieldwork with these militants.

The music is off. Everyone is pulling on jackets and boots. It is three AM and we are on the street before I can hand Pacho a fresh battery for the camera.

Rimi, Pero, and Marin scan the walls with care as we near the most politically charged terrain in Zagreb’s urban landscape: the Square of the Victims of Fascism. After the HDZ came to power in 1990, they renamed this intersection of six streets—all converging on a traffic circle around a dramatic columned pavilion,10 the Square of Croatian Greats (see figure 1.2)—as part of a larger strategy of recasting the urban landscape with nationalist nomenclature. A coalition of human-rights NGOs, younger activists, and the elderly Alliance of Antifascist Fighters (SAB) protested this decision. The participation of the SAB in these annual demonstrations incensed the right because the aging veterans of the successful World War II antifascist resistance fought the quisling Ustaša regime and occupying German forces under Marshal Tito’s leadership, helped found SFRY, and enjoyed the status of national heroes during socialism. Rimi described the violent clashes with far-right counter-demonstrations as the first time he had “faced off with fascist trash.” When the former communist Social Democrats returned to power in 2000, this square was rededicated to the Victims of Fascism. If the right-left conflict is no longer fought openly here, it is carried on by other means: spray-paint.11 We find one of Pero’s graffiti, “Freedom Begins With the Death of the State,” altered to read, “Freedom Begins With the Death of the Communist State.” “Skinheads (skinjari),” Pero mutters, shaking his head. This rightist graffito editing aside, the left appears triumph...