![]()

1

New Investigations into the Iguanodon Sinkhole at Bernissart and Other Early Cretaceous Localities in the Mons Basin (Belgium)

![]()

1

Bernissart and the Iguanodons: Historical Perspective and New Investigations

Pascal Godefroit*, Johan Yans, and Pierre Bultynck

The discovery of complete and articulated skeletons of Iguanodon at Bernissart in 1878 came at a time when the anatomy of dinosaurs was still poorly understood, and thus considerable advances were made possible. Here we briefly describe, mainly from documents in the archives of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, the circumstances of the discovery of the Bernissart iguanodons. We also provide information about their preparation and mounting in laboratories, for exhibitions, and in early studies. We also summarize the latest results of a multidisciplinary project dedicated to the material collected in the cores drilled in 2002–2003 in and around the Iguanodon Sinkhole at Bernissart.

1.1. The Sainte-Barbe pit and mine buildings in 1878, at the time when the iguanodons were discovered.

The Bernissart Iguanodons: A Cornerstone in the History of Paleontology

The discovery of the first Iguanodon fossils has become a legend in the small world of paleontology. Around 1822, Mary Ann Mantell accompanied her husband, the physician Dr. Gideon Algernon Mantell, on his medical rounds and by chance discovered large fossilized teeth. Her husband found the teeth intriguing. With advice from Georges Cuvier, William Clift, and William Daniel Conybeare, he described them and named them Iguanodon, “iguana tooth,” because of their superficial resemblance to those of living iguanas (Mantell, 1825). Iguanodon was one the three founding members of the Dinosauria—along with Megalosaurus and Hylaeosaurus—named by Richard Owen in 1842.

For 56 years, little was known about Iguanodon and other dinosaurs. Mantell imagined these antediluvian animals to be some kind of giant lizards with elongated bodies and sprawling limbs (Benton, 1989). In 1854, the sculptor Waterhouse Hawkins, following Owen’s advice, realized full-size reconstructions of Iguanodon and Megalosaurus for the Crystal Palace exhibition in London. Iguanodon was reconstructed as a rhinoceros-like heavy quadruped with a large spike on its nose. These impressive monsters invoked the first public sensation over dinosaurs (Norman, 1985).

The first partial dinosaur skeleton, named Hadrosaurus foulkii Leidy, 1858, was discovered in 1857 in New Jersey. This skeleton was reconstructed in a bipedal gait at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, but many questions were still left unanswered about the general appearance of dinosaurs.

Then, 20 years later, another Iguanodon discovery broke the scientific world—and the dinosaur world—wide open (Forster, 1997). The discovery of complete and articulated skeletons of Iguanodon at Bernissart in 1878 revealed for the first time the anatomy of dinosaurs, and thus considerable advances were made possible, in combination with the remarkable discoveries in the American Midwest described by Marsh and Cope (Norman, 1987).

Many manuscripts and plans relating to the original excavations at Bernissart are preserved in the paleontological archives of the RBINS, which allow us to reconstruct the circumstances of the discovery of these fantastic dinosaurs.

Institutional abbreviations. NHMUK, The Natural History Museum, London (formerly the British Museum [Natural History]), U.K.; RBINS, Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Brussels (formerly MRHNB, Musée royal d’Histoire naturelle de Belgique), Belgium.

The Discovery and Excavation of the Bernissart Iguanodons

Bernissart is a former coal-mining village in southwestern Belgium, situated 21 km south of Mons and less than 1 km from the Franco-Belgian frontier. Pre-industrial coal extraction began at Bernissart around 1717 (Delguste, 2003). In 1757, Duke Emmanuel de Croÿ grouped together the different coal companies in northern France into the powerful Anzin Company, which started the industrial exploitation of the coal in the Bernissart area during the second half of the eighteenth century (Delguste, 2006). In the nineteenth century, the Bernissart Coal Board Limited Company dug five coal pits on Bernissart territory. The Négresse pit (no. 1, exploited from 1841) and Sainte-Barbe pit (no. 3, exploited from 1849; Fig. 1.1) were used for coal extraction and coupled with the Moulin pit (no. 2, exploited from 1842) for ventilation. The Sainte-Catherine pit (no. 4, exploited from 1864) was the third extraction pit and was coupled with pit no. 5 (exploited from ?1874) for ventilation. The maximum distance between pits 1 and 5 was about 1,600 m. With a depth of 422 m, the Sainte-Barbe pit was the deepest. In spite of a rather archaic technology, the daily production for the three extraction pits was about 800 tons. However, the flood problems were more important than in other coal mines from the Mons area; steam pumps were used to extract the water.

On February 28, 1878, miners digging a horizontal exploration gallery 322 m below ground level suddenly encountered, 35 m to the south of the Luronne seam, disturbed rocks, indicating that they were penetrating inside a vertical cran—a local term meaning a pit formed by natural collapse through the coal seams that was filled especially with clayey deposits normally located above the coal measures.

On March 1, chief overseer Cyprien Ballez, engineer Léon Latinis, and mine director Gustave Fagès went down into the Sainte-Barbe pit to evaluate the situation. It was decided to traverse this cran and to rejoin the coal seam on the other side. Overseer Motuelle and miners Jules Créteur and Alphonse Blanchard were put in charge of continuing the exploration gallery through the perturbed layers of the cran. On March 9, Ballez noticed that the exploration gallery was still in the perturbed zone of the cran.

In March, the miners had already collected dinosaur remains: fragmentary bones and teeth, which are labeled “remains of the first Iguanodon, March 1878” and are housed in the paleontological collections of the RBINS. But they apparently paid little attention to these discoveries, believing that they were just fossil wood.

On April 1, the exploration team again entered nondisturbed but inclined formations. On April 3, Ballez and Latinis went down again together in the exploration gallery. The engineer estimated that they had again reached coal-bearing formations. Latinis’s explanations apparently did not satisfy Fagès. Indeed, the mine manager decided to accompany the engineer and the chief overseer in the exploration gallery on April 5. While inspecting the deposits, Fagès found a long object with an oval cross section and a fibrous texture. Latinis believed that it was a fossil oak branch. Conversely, Fagès ironically asserted that it was a rib of Father Adam. Miner Jules Créteur mentioned that he had already found a larger fossil, and the team soon unearthed limb bones in the gallery. In the evening, miners brought several fragments of these fossils to Café Dubruille. There the local doctor, Lhoir, who also worked for the coal mine, burned one of the fragments and confirmed that the fossils collected by the miners were bones, not wood. Many new fossils were discovered by the miners in the night of April 5–6. On April 6, Fagès ordered Ballez to bring all the fragments of bones that the miners had collected to the surface and to lock up the end of the gallery.

On Sunday, April 7, Latinis was commissioned to go to Mons to show the fossils to the well-known geologist François-Léopold Cornet. But Cornet was not home. Latinis thus left the fossils to his young son, Jules (a future renowned geologist), and asked him to tell his father that these bones had been found in the Sainte-Barbe pit at Bernissart.

On April 8, F.-L. Cornet came to Bernissart and briefly discussed the Bernissart discovery with Latinis. He could not meet Fagès, who was with Ballez in the Sainte-Catherine pit. On April 10, Cornet told the zoologist Pierre-Joseph Van Beneden, professor of paleontology at Leuven University, that Latinis, who was a former student of Van Beneden, had discovered fossil bones at Bernissart, and he sent him some of the bones that Latinis had left with his son. Van Beneden quickly identified the teeth as belonging to the dinosaur Iguanodon, previously described from Wealden deposits in England.

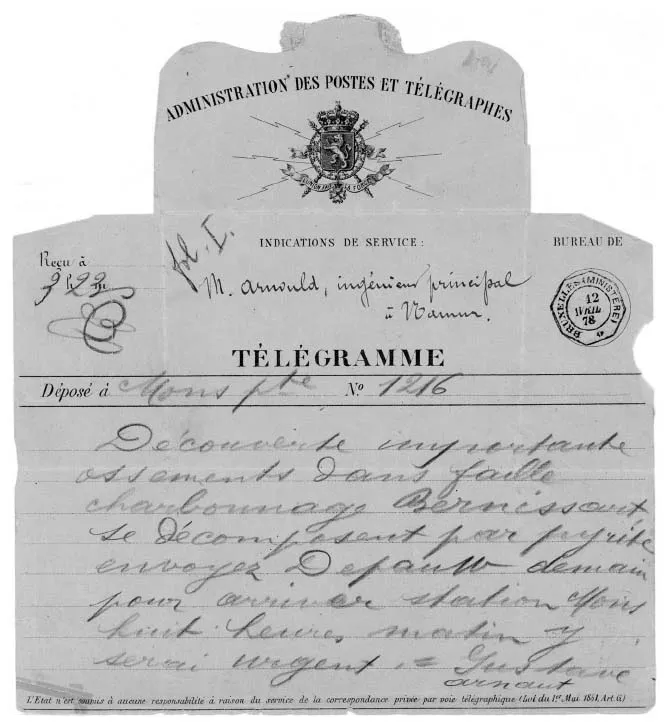

On April 12, Fagès went to Mons to meet the chief mining engineer, Gustave Arnould, who immediately sent a telegram to Edouard Dupont, director of the Musée royal d’Histoire naturelle de Belgique (MRHNB) at Brussels to inform him of the important discovery at 322m below ground level in the Sainte-Barbe Pit (Fig. 1.2).

On Saturday, April 13, Louis De Pauw, head preparer at the MRHNB and a man who already had extensive experience in the excavation and preparation of fossil vertebrates, met Arnould at Blaton. They went together to Bernissart. Fagès showed them the bones recently found in the gallery; De Pauw recognized two ungual phalanges and one vertebral centrum. It was then decided to go down together into the fossiliferous gallery. De Pauw (1902) reported that the walls of the exploration gallery were completely covered by fossil bones, plants, and fishes. Ballez, Motuelle, Créteur, and Blanchard soon unearthed a complete hind limb that they transported on a plank covered with straw. But after a 300-m walk, the bones began to disintegrate on contact with the fresh air of the mine galleries. De Pauw protected the biggest remaining fragment with his own clothes, and Ballez and Motuelle brought the fossils to the surface. De Pauw realized that the presence of pyrite inside the bones was one of the biggest problems that they had to face if they were to unearth the fossils from the Sainte-Barbe pit. He packed the collected bones in a box full of sawdust and brought them back to Brussels. In MRHNB workshops, he succeeded in solidifying the limb bones from Bernissart with gelatin. In the meantime, Latinis prepared 11 more boxes full of fossils at Bernissart.

1.2. Telegram of April 12, 1878. Translation: “Important discovery of bones in coalfield fault Bernissart decomposing due to pyrite. Send De Pauw tomorrow to arrive Mons station 8 a.m. Shall be there. Urgent. Gustave Arnaut.”

Fagès quickly gathered together the board of directors of the Bernissart Coal Board Limited Company. They decided to donate the fossils discovered in the Sainte-Barbe pit to the Belgian state and to notify Charles Delcour, minister of the interior, and Edouard Dupont, director of the MRHNB, about this decision. But the excavations could not immediately begin because the MRHNB team was busy preparing for the Paris World’s Fair.

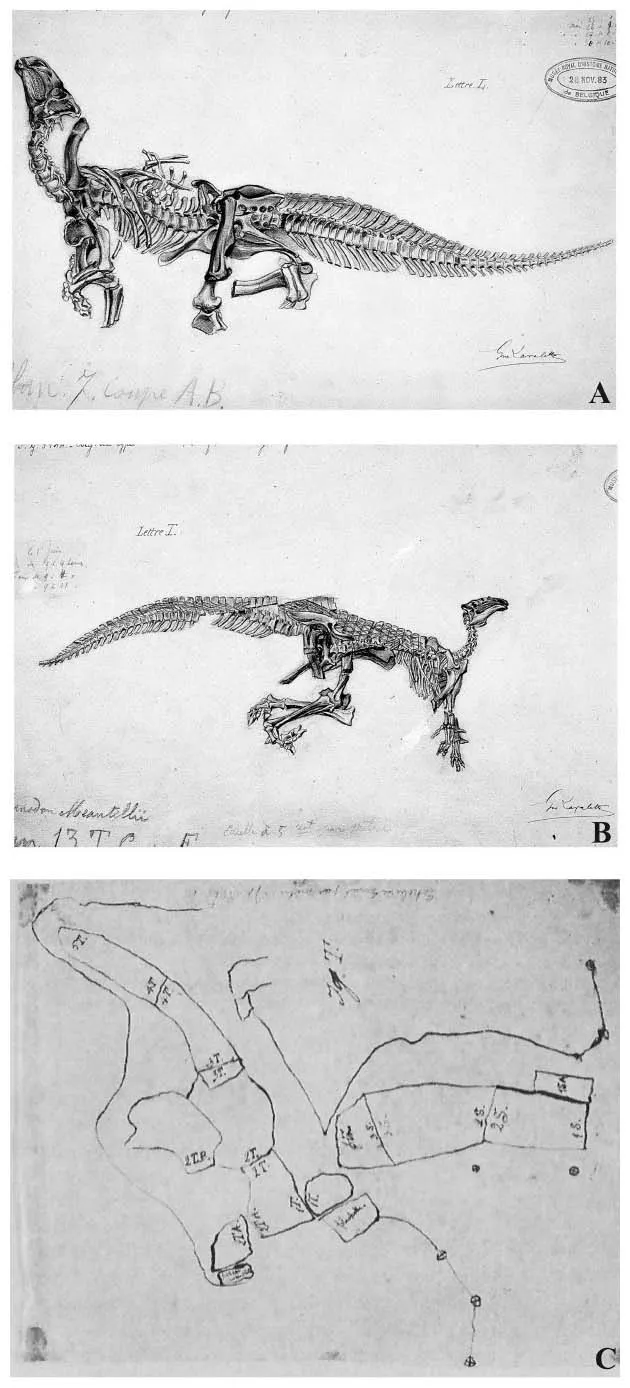

De Pauw settled in Bernissart on May 10, and the excavations began on Wednesday, May 15. The excavation team included one warder (M. Sonnet) and one molder (A. Vandepoel) from the MRHNB, six miners (J. Créteur, A. Blanchard, J. Gérard, E. Saudemont, D. Lesplingart, and Dieudonné), and the overseers Ballez, Mortuelle, and Pierrard. Every day from 5:30 in the morning until 12:30 in the afternoon, the team went down into the Sainte-Barbe pit. The excavation method De Pauw created proved to be efficient and is still used today during paleontological excavations. Each Iguanodon skeleton was split into pieces. The exposed bones were first covered by wet paper or liquid clay and coated by a layer of plaster of Paris. The fossils were then undercut in a bed of matrix and the reverse side plastered. The block was then reinforced with either strips of wood or steel, then coated with a second layer of plaster. After being sketched and cataloged (Fig. 1.3), the blocks were carried to the surface. Every afternoon, from 3:00, the team collected fossils on the coal tip in sediments previously extracted from the pit (De Pauw, 1902).

1.3. A, Drawing by G. Lavalette in 1883 of specimen “L” (RBINS R56) of Iguanodon bernissartensis, as discovered in the Sainte-Barbe pit. B, Drawing by G. Lavalette in 1882 of specimen “T” (RBINS R57) of Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis, as discovered in Sainte-Barbe pit. C, Sketch of the assemblage of plaster blocks containing pieces into which specimen “T” (RBINS R57) was divided for raising to the surface. Block “1T” contains the skull and “5T,” the end of the tail of this individual.

In August 1878, a big earthquake blocked the excavation team for 2 hours in the gallery 322 m below ground level. This gallery was subsequently flooded, and on Tuesday, October 22, the team was forced to abandon their work for several months. The tools and the last fossiliferous blocks had to be left behind in the flooded galleries. At that time, five skeletons of Iguanodon had already been discovered, although only that of “A” (RBINS VERT-5144...