THE 50 GREATEST

PREHISTORIC SITES

OF THE WORLD

THE VÉZÈRE VALLEY

Location: Dordogne, France

Type: Various

Period: Various

Dating: 440,000 BP–12,000 BP

Culture: Various

Any other valley would consider itself blessed just to have within its boundaries a handful of the 147 Paleolithic sites and 25 painted caves lined with the world’s finest prehistoric art that lie scattered throughout the Vézère Valley in South-west France. That so much lies within so compact an area makes this meandering, limestone-encrusted valley one of the world’s premier prehistoric hotspots, with a preserved topography of rock shelters and overhangs that still testify to the sort of terrain prehistoric man was looking for when deciding where he should ‘settle down’. One of the cradles of European civilisation, humans have inhabited the Vézère Valley for more than 440,000 years, with flints dating that far back having been unearthed beneath a rock shelter at La Micoque on the right bank of the Vézère River near the town of Manaurie, in 1895. Excavations at La Micoque continued without interruption until the early 1930s, and the rock shelter has since been found to have been continually occupied for more than 300,000 years.

Excavations began in the valley in 1863, with the Vézère River’s meandering south-west course through the Dordogne a legacy of a great inland sea that once covered the Aquitaine region, only to retreat and leave in its wake a complex terrain of limestone plateaus and eroded valleys. Many of the valleys had galleries cut into their sides which in time developed large overhangs that gave protection from the weather and made ideal dwelling places for primitive man. It’s difficult to know where to start when cataloguing the valley’s wonders, though most would begin, no doubt, with a visit to Lascaux II. The replica cave opened in 1983 after the closure of the original, and fragile, Lascaux Cave in 1963. The original cave, which remained undiscovered until 1940, is over 17,000 years old and is filled with more than 2,000 drawings of humans and animals, as well as various symbolic and abstract signs. Lascaux II is its mirror image, created utilising the same techniques and pigments used in the original cave.

In the 25 kilometre length of the Vézère Valley between the towns of Les Eyzies and Montignac, there are fifteen caves with UNESCO World Heritage status. The Grotte de Rouffignac contains over 250 twelve-thousand-year-old friezes of mammoths and woolly rhinoceroses, all gorgeously rendered in black, painted in flickering candlelight by a small number of men and women – the Cro-Magnons, the first Homo sapiens to settle in Europe – who laid on their backs with the ceiling barely a metre above their heads to create what can still be seen today. Now referred to simply as ‘The Great Ceiling’, the floor has been lowered to allow for better access, and if you look closely you can even see scratch marks on the walls, made by hibernating bears from eons ago. Also a must-see is the Grotte de Font-de-Gaume with its 200-plus polychrome paintings (including bison, horses and mammoth) as well as Magdalenian-period engravings. The entrance to the Font-de-Gaume cave was first settled 25,000 years ago, and it is the only cave with coloured artwork remaining in France that can be visited, although access is extremely limited.

The valley is also home to some quite extraordinary friezes of animals sculpted directly into its abundant limestone, the most majestic of which is the Abri du Cap Blanc, a thirteen-metre-long frieze and one of the world’s finest examples of Paleolithic sculpture to have survived the Ice Age, still possessing outstanding depth and quality. The frieze consists of horses, bison and deer, and is the only frieze of prehistoric sculptures now open to the public. Another extraordinary though very small cave, located in the Gorge d’Enfer near to the village of Les Eyzies is the Abri du Poisson (circa 23,000 BCE) and its metre-long, life-sized sculpture of a male salmon (with a hook in its mouth!) etched into its ceiling. Access to the cave is by prior arrangement, but is worth the experience not only because fish are rarely represented in either cave paintings or rock engravings, but mostly because once you’re inside all you have to do is look up: this remarkably well-preserved sculpture is right above your head.

Another site that should not be missed is La Roque Saint-Christophe, a spectacular wall of limestone a kilometre in length and 80 metres high that rises along the banks of the Vézère River. Punctuated with a wealth of shelters and overhanging terraces hollowed out of the soft limestone, it began as a home for Neanderthal man 50,000 years ago, and has continued as a much-coveted defensive sanctuary ever since for Cro-Magnon people, Neolithic man, Gauls, Romans, Normans and Medieval princes. It was even a Renaissance-era troglodyte town and fortress that once occupied five levels of its cliff-face, the empty post holes in the limestone still clearly visible. There are no caves, and so no cave art either, and because of the constant use the site has received, what evidence there would have been of its earliest inhabitants has long since been obliterated. Now all that remains are various reconstructions of prehistoric and medieval life such as campfires, capstans, winches and cranes. But the limestone overhangs and shelters are extraordinary in their breadth and scale, and even include Europe’s largest stone staircase hewn out of a single piece of rock, the medieval ‘great staircase’. And yes, you can walk on it, too.

Those who live in this prehistoric valley are aware of the need to be good stewards. The owner of the Château de Commarque, Hubert de Commarque, has been not only restoring the castle since he purchased the site in 1962, but preserving its considerable prehistoric legacy including the remnants of a troglodytic community and the castle’s very own Magdalenian-era sculpture of a horse’s head in a sealed cave beneath its extensive fortifications.

The National Museum of Prehistory in Les Eyzies has the finest collection of prehistoric artefacts in France including a magnificent bas-relief carving on a fragment of a reindeer’s antler just a few centimetres in length depicting a now-extinct Steppe bison licking its flank (perhaps an insect bite?). Carved with great delicacy, it is all that remains of a spear thrower dating to the Magdalenian culture between 20,000 and 12,000 BCE; another reminder that the treasures of the Vézère Valley come down to us in both the very large, and the very small.

ATAPUERCA

Location: Atapuerca Mountains, Northern Spain

Type: Cave burial

Period: Pleistocene–Iron Age

Dating: 430,000 BCE–600 BCE

Culture: Neanderthal–Modern Man

There’s barely a period of human habitation in Europe that the site of Atapuerca on Spain’s Iberian Peninsula doesn’t attest to. The Pleistocene (Trinchera del Ferrocarril and Cueva Mayor), the Holocene (El Portalon de Cueva Mayor and Cueva del Silo), the Paleolithic, the Neolithic, the Bronze and Iron Ages, and over the divide into the pages of history to the Medieval period and beyond. A million years of history in one single, extraordinary site.

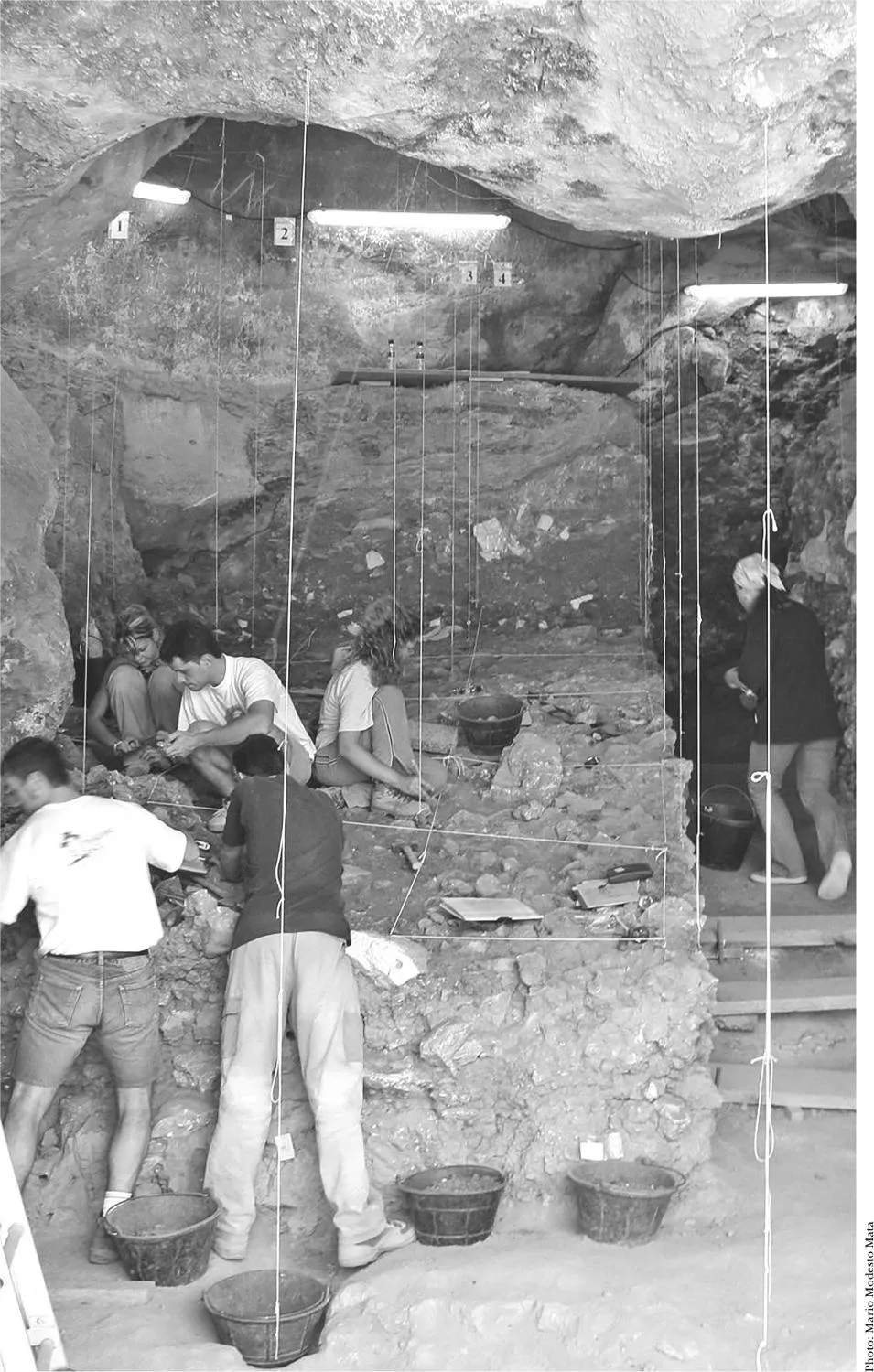

Located not far from the city of Burgos in the Atapuerca Mountains, a limestone-laced range filled with all manner of caves, tunnels and sinkholes, Atapuerca’s existence was first noted in an abstract reference to human remains published in a Spanish newspaper in 1863. Ninety-nine years later a team of spelunkers (cave divers) stumbled upon the cave and notified the local museum in Burgos, and in 1976 a mining engineer searching for bear fossils found a humanlike mandible. Atapuerca gave up its secrets slowly.

The site contains a fossil record of Europe’s earliest humans that is second to none, including the fragments of a jawbone and teeth dating to 1.2 million years ago – Homo antecessor – found in the ‘Pit of the Elephant’, the earliest known remains of humans to be found in Western Europe. It contains a record of occupation containing evidence not only of the earliest inroads made by civilisations that still are with us today, but of those that have long since ceased to be. Atapuerca’s ideal location in terms of climate and geography contributed to its longevity, and in addition to the fossil record there are paintings and panels that shed additional light onto the everyday lives of its inhabitants, depicting hunting scenes as well as geometric motifs and a wealth of human and animal-like figures.

One of the most famous discoveries made at Atapuerca is the legendary ‘Pit of Bones’, accessed via a vertical chimney, which first began to be studied in 1984, and again with renewed efforts after additional fossils were uncovered, in 1991. The 400,000 year-old bones – Homo heidelbergensis – found in the Pit of Bones from the Middle Pleistocene, a total of more than 6,700 fossils, belonged to 28 individuals of all ages and both sexes. They were heavier than later Neanderthals, around 150 pounds (68 kilograms), yet their brains were smaller, and the evidence gathered enabled studies to be made in the evolution of modern humans’ body shapes. The work here has also enabled scientists to identify four primary stages of human evolution over the past 4 million years: ardipithecus (arboreal and maybe bipedal); australopithecines, similar to the famous Lucy, mostly bipedal and possibly arboreal; archaic humans, the sort found at Atapuerca that belong to the group Homo erectus; and finally modern humans. Whether or not the bodies found here were purposely thrown in by their contemporaries in an act of burial is still hotly debated.

What is extraordinary about the findings at Atapuerca is that they include Neanderthals – archaic humans, in their ‘third stage’, putting an end to the theory they were merely a product of the adaptation required to live in the cold climates of Europe. The more of Atapuerca’s secrets that are uncovered, the more long-held theories about the distinctions between Homo erectus and the Neanderthals seem to evaporate. They now seem more like us than ever before. And just like us, thanks to a discovery in the Pit of Bones, even during a period of human history not known for its acts of violence because there were no territories to defend, a Neanderthal could still be provoked to murder.

Four hundred and thirty thousand years ago a disagreement took place between two Neanderthals that ended in a young adult being killed by two blunt force traumas to the skull. The similarity of each fracture suggests both blows were made with the same instrument, and the incident became the first known act of lethal violence to occur in the Homo genus. The cranium’s two wounds, T1 and T2, were not the result of a fall or accident. They were deliberate multiple blows delivered with the intention to kill. Chemical analysis of the remains revealed that the wounds had failed to heal before the person died, confirming the man or woman had died of their injuries. Found in a deep layer of red clay known as LH6, the skull’s first fragments were found in 1990 and pieced together years afterwards when its remaining pieces were uncovered. While it’s unclear what the weapon may have been, the wound is consistent with it being either a spear or some kind of stone axe.

The world’s first recorded murder makes for an extraordinary piece of forensic paperwork. AGE: Unknown. SEX: Unknown. CAUSE OF DEATH: Blunt force trauma. TIME OF DEATH: 430,000 BCE … give or take.

The commonly accepted notion of ‘encephalisation’, the evolutionary increase in the size and complexity of the brain, is also in danger of being undone by the discoveries at Atapuerca. No longer was Homo erectus presumed to be the singular, fortunate recipient of an evolving brain. According to the brain mass determined by the skeletal evidence at Atapuerca, the process occurred rapidly among Neanderthals too. Perhaps they were not the ‘super chimpanzees’ science had led us to believe. They talked, they clothed themselves and they evolved independently of us. They were our ‘mirror species’.

ÉVORA COMPLEX

Location: Alentejo, Southern Portugal

Type: Dolmen, menhirs, cave dwelling

Period: Neolithic–Chalcolithic

Dating: 50,000 BCE–3,000 BCE

Culture: Various

The Évora Complex is the name given to a collection of megalithic and other prehistoric sites concentrated around the town of Évora ...