![]()

CHAPTER I

Interim steps

The secret to getting ahead is getting started. The secret to getting started is breaking your complex, overwhelming tasks into small manageable tasks, and then starting on the first.

Mark Twain

try it now

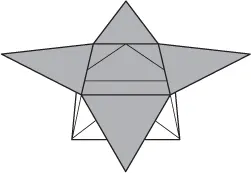

Find a square of paper, approximately 20×20 cm. Your task is to make the origami box shown above.

So how did you get on with making your own box? What do you mean you can’t do it?

This box may look overwhelmingly complicated to make, but in reality it’s just a sequence of simple folds, carried out in the right order. The secret to making the box is focusing on achieving one step at a time, breaking the complex whole down into a series of simple baby steps. You will find the instructions at www.thesuccessagents.com/origami-instructions if you want to impress your friends and family with your origami folding skills!

This box is a representation of your goal. It may appear complex on the face of it, so to succeed you need to break the goal down into a series of manageable steps and know the order you need to complete them in.

HAVE AN ACTION PLAN

Professor of Psychology at New York University, Peter Gollwitzer, has found that people who plan in advance the steps that will be taken to achieve a goal (including when, where and how action will be taken), achieve greater success. Gollwitzer calls the plan that you create an implementation intention.

Professor Gollwitzer’s research shows that people who use implementation intentions are more likely to achieve large, ambitious goals than people who do not set them.

Implementation intentions also help you to achieve smaller goals too. For example, it has been shown that the number of healthy foods (i.e. fruit and vegetables) a person eats can easily be increased if they are asked to form implementation intentions on what they will eat for the different meals of a given day. So now you know what to do if you want to reach your ‘five a day’ target!

Another reason that breaking your goals down into baby steps helps you to succeed is that it helps you to believe that you can do it.

For example, the goal, ‘I want to be able to run the London Marathon, in less than four hours, next year,’ is very daunting, whereas the task of going to a running shop and selecting the right footwear for running is relatively easy.

The breaking down of goals into manageable steps is something that has been used successfully for years. At the 1972 Olympics held in Munich, Mark Spitz won seven gold medals for swimming, breaking an impressive seven world records on the way.

Seventeen-year-old John Naber was so impressed by Mark’s achievements he set himself the goal of winning the gold in the 100 metre backstroke at the next Olympics in 1976. However, John’s current personal best was only 59.5 seconds, compared to the winning time of 56.3 seconds.

John realized that he was going to have to do better than that, so set himself a target of 55.5 seconds (notice that’s a specific and measurable goal). If he was going to achieve this time (which would be a world record) he would have to go four seconds faster over the next four years. So, to break it down, that’s one second per year he needed to improve by. Because swimmers train for about ten months a year, he divided that goal of one second each year down to 1/10th of a second each month.

John didn’t stop there. He worked out that as he trained six days a week, that broke it down to 1/300th of a second a day. And then he took it even further: he trained for four hours a day – that made it 1/1200th of a second each hour. To put that into context, if you blink your eyes, the time it takes them to close is 5/1200ths of a second. Now, doesn’t his ambitious dream now sound like a realistic goal?

While John may initially have aimed high, setting himself a goal he didn’t believe he could achieve, by breaking it down into the smallest of measurable steps he was able to make sure he had a path to achieve his end goal.

And the result of his implementation intention? He won the gold in both the 100 metre and the 200 metre backstroke, the first in world record time (55.49 seconds) and the second in Olympic record time. He had made what seemed impossible to him very much possible and achieved his dream of holding an Olympic gold medal.

BELIEVE IN YOUR ABILITY

This relates to a well known theory in psychology called self-efficacy, a term coined by Albert Bandura in 1977. Self-efficacy is a person’s belief in his or her ability to succeed in a given situation.

I am the greatest’, I said that even before I knew I was.

Muhammad Ali

People with strong self-efficacy are more likely to achieve their goals than people with weak self-efficacy, who will likely avoid challenging tasks, believing them to be beyond their capabilities.

One of the benefits of breaking your goals down into manageable chunks is that even a person with low self-efficacy can achieve tasks and work towards a major goal, because the smaller tasks are not so daunting.

try it now

Have a go at beginning to develop your own implementation intention plan, to support you to achieve your goal. Here’s what to do:

- Grab three pads of Post-it notes, all different colours, say yellow, green and orange.

- On the green Post-it note write your major goal. Make it specific and measurable (e.g. ‘I want to have my own business, earning at least as much money as I do now through my current job, within three years.’).

- On the yellow Post-it notes brainstorm all of the things that you need to do to achieve your goal (e.g. ‘think of a company name’; ‘buy a website’; ‘produce marketing fliers’; ‘get business cards’; ‘find my first client’; ‘open a business bank account’; ‘get professional indemnity insurance’; etc.).

- Now, sort all of your yellow Post-it notes into themes of related items. For example, ‘buy a website’, ‘produce marketing fliers’ and ‘get business cards’ might go in a cluster under ‘marketing’.

- Next, put the Post-it notes in order of when you need to achieve them. Your aim is to create a line of Post-it notes that stretches from the first action that you need to take, all the way to the green Post-it note at the end.

- Finally, look at the date that you have set for yourself to achieve the end goal and, using the orange Post-it notes, make a timeline by putting dates next to your actions (e.g. the first action might have a Post-it note saying ‘tomorrow’ next to it).

![]()

CHAPTER J

Just have a go!

The man who makes no mistakes does not usually make anything.

Edward John Phelps

You may know people who have hopes and dreams but frustratingly, never do anything about them. To put it another way, they procrastinate, which University of Calgary lecturer Piers Steel defines as ‘voluntarily delaying an intended course of action despite expecting to be worse off for the delay’.

Perhaps you are procrastinating over something that you want. If so, read on.

WHY DO WE PROCRASTINATE?

Psychologists such as Barbara Fritz at the University of Florida are fascinated by the question of what makes us procrastinate. It has been concluded that there are two key reasons we do.

One reason is fear of failure – we are worried that we aren’t going to do the task particularly well and so put it off and prefer to do things we are ‘better’ at (such as watching television or playing football).

The other main reason is labelled task aversion, or to put this in a non-jargon way – we hate doing it because it’s an awful bind compared with something more enjoyable (such as watching television or playing football!).

WHY DO WE HAVE A FEAR OF FAILURE?

Have you ever seen parents trying to coach their toddler to walk? What is their reaction when Junior takes his first steps and falls right over on his bottom? Do Mum and Dad yell in rage? Of course not – they cheer! Junior just walked!

So what goes wrong? Somewhere between learning to walk and becoming an adult, instead of being encouraged to try and being rewarded for trying even though we failed, we somehow are taught that we must get it right first time.

For example, at work we avoid giving presentations, fearing that we will look stupid. Or perhaps we are just scared of taking the wrong decision and making a mistake. To avoid being punished, we procrastinate and hope that someone else will act instead.

Yet the fact of the matter is that no toddler ever got up and walked perfectly for ten minutes on the first attempt. No teenager ever got into a car and drove faultlessly for 100 miles first time. We fall, we stall and that is the way that it has to be in order for us to learn.

OVERCOMING THE FEAR OF FAILURE

Key to the psychology of success is how you view failure. Once you’ve accepted the principle that you have to try in order to succeed, the next key steps are to:

- Find ways to see a failure as a good result

- Re-label failure as a learning opportunity.

Don’t worry about failure, worry about the chances you miss when you don’t even try.

Harvey Mackay

WHY DO WE SUFFER FROM TASK AVERSION?

Many, many people will be able to identify with the feeling of desperately wanting to get in shape but still not having enough motivation to get up early and go to the gym.

At the heart of this is the fact that we think of things like going to the gym as painful. When you have the choice of getting up (while it is still dark, yuck!) and dragging yourself to the gym before work or else having an extra hour in your warm cosy bed, it isn’t really a difficult choice is it? Getting up is painful; staying tucked up under the duvet is pleasurable.

We therefore associate taking action with pain and not taking action with pleasure, hence we don’t act. But what implication does this have?

A friend of ours, Becky, had been in a relationship for nine years and was engaged to b...