IntroductionRichard Wellings

The depletion of fish stocks has proved to be a difficult problem to resolve. A high proportion of the world’s fisheries are thought to be ‘over-exploited’ and yields are likely to fall in the long term. Declining catches will then have a significant wider economic impact. Around 35 million people are directly employed by the fishing industry, with a multiple of this engaged in processing and support jobs (FAO 2014). Moreover, fish comprise roughly 20 per cent of the animal protein in people’s diets and often a much higher percentage in poorer countries (ibid.). While the fishing industry makes up only a small fraction of ‘gross world product’, perhaps 0.25 per cent, its share of GDP is far larger in many developing economies, including Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam.

The importance of the ‘fisheries crisis’ goes beyond its economic impact. The depletion of stocks is symptomatic of a far wider problem with ‘open access’ resources. Policies that prove effective for the fishing industry are therefore likely to have wider relevance to issues such as overgrazing of grasslands and deforestation – at least in terms of general principles.

This collection examines the economic and political causes of the problems faced by fisheries and also sets out potential solutions. If a theme unites the contributions, it is that one-size-fits-all approaches are ill-suited to this policy area, both in analysing how depletion arises and developing strategies to address it. Moreover, measures that might appear attractive in terms of economic theory may be undermined by the incentives facing political actors in the locations where they are applied.

The remainder of this introductory chapter provides a critical overview of the major issues facing the fisheries sector and a summary of key theoretical explanations for the current crisis. It argues that standard analyses of ‘overfishing’ are often simplistic and fail to acknowledge adequately the role of states in undermining market feedback mechanisms that would help to protect stocks.

Similarly, government action often weakens or destroys voluntary and/or community-based arrangements between fishermen, sometimes with disastrous consequences. Finally, it is clear that limited intervention in the form of the creation and enforcement of property rights is likely to be more efficient than more active state regulation of the sector.

Global fish stocks

The foregoing discussion alludes to severe problems with the world’s fisheries. Indeed, much analysis of this issue begins with the assumption that several species are close to depletion. It is claimed that the oceans are likely to become ‘virtual deserts’ within the next few decades. The reality is rather more complex. In some respects the fishing industry could be viewed as a success story. Overall global fish ‘production’ has increased by a factor of eight since 1950, far outstripping population growth and enabling per capita consumption of this protein-rich food to almost treble to 19 kg per year (FAO 2014).

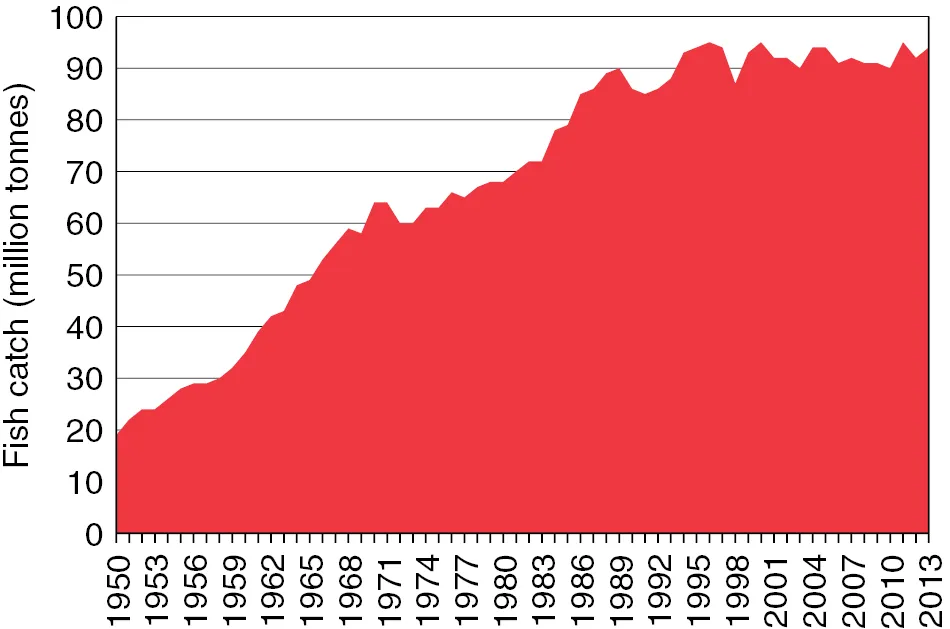

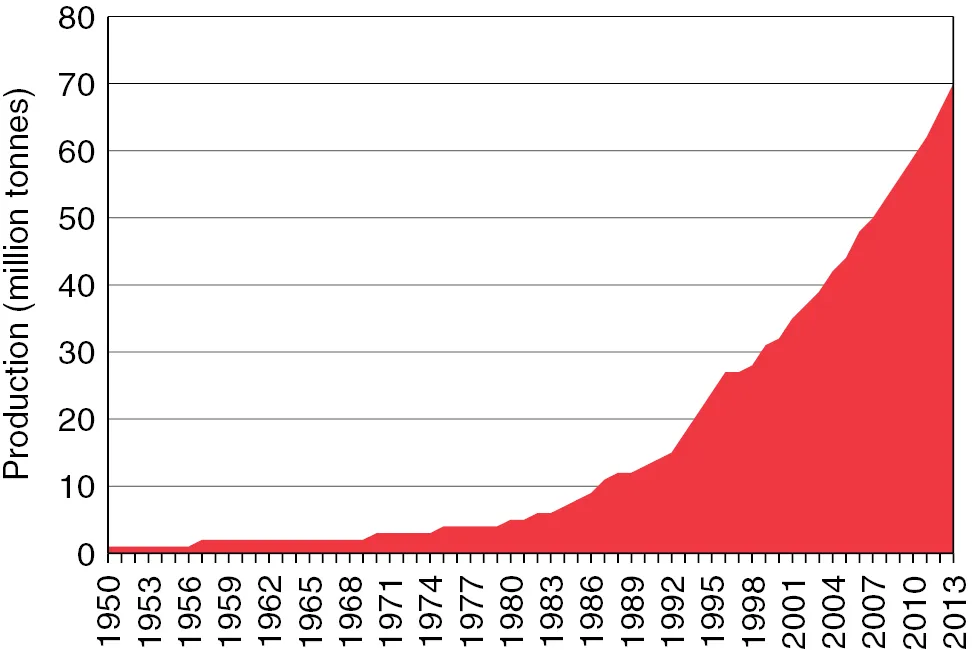

The aggregate data hide some worrying trends, however. Following a long period of steady growth, annual catches of wild fish in the seas, oceans and inland waters appear to have stagnated at around 90 million tonnes since the mid 1990s (Figure 1). A major expansion in fish farming therefore explains recent increases in supply (Figure 2). In particular, market-friendly reforms in China since the late 1970s have encouraged rapid growth in its aquaculture sector (FAO n.d.).

Figure 1 Global fish catch, 1950–2013 (wild capture)

Source: FAO (2014).

Figure 2 Global fish production from aquaculture, 1950–2013

Source: FAO (2014).

In the same period, many long-established sea fisheries have experienced substantial declines in catches. In the North West Atlantic, for example, landings have fallen by approximately 55 per cent since the 1968 peak (FAO 2011). Worse still, within these totals, the yield of certain species has collapsed. Perhaps best known is the 98 per cent fall in cod catches in the North West Atlantic between 1968 and 2003 (ibid.: 24), with the species virtually disappearing from the seas off Canada where it was once abundant.

A decline in the quality of catches has also been evident in several major regions. The share of high-value fish such as cod and wild salmon has been falling, while that of low-value species such as blue whiting and sand eels – typically used to make fishmeal or fish oils – has increased. Aggregate tonnage figures may therefore mask the extent to which fish stocks have been degraded. Moreover, they may not reflect the environmental damage caused, for example, to seabeds by beam trawling or to marine creatures not targeted by fishermen but nonetheless killed or injured by their practices (see Moore and Jennings 2000).

Given the decline in many long-established fisheries, growing catches in previously little-exploited regions such as the Eastern Indian Ocean have helped maintain levels of global supply (ibid.). Nevertheless, there are fears that these emerging fisheries will follow a similar trajectory, with growth phases a precursor to declining overall yields and a collapse in high-value species.

Such a hypothesis underlies the predictions that global fish catches will fall precipitously by the middle of the twenty-first century, with this view often combined with forecasts that climate change and marine pollution will also have a devastating impact on yields (Worm et al. 2006; Allison et al. 2009).

There is good reason to believe, however, that such concerns are overstated. Firstly, in many fishing grounds stocks appear to be stabilising or even recovering after previous slumps. And, within such fisheries, the situation may vary markedly by species. This makes an across-the-board collapse unlikely. Secondly, at least some of the environmental problems seem to have been mitigated, particularly in developed regions where high living standards have increased the demand for ‘environmental goods’ such as clean seas and fish caught without damaging other species. Thirdly, there is arguably growing awareness of the policy mistakes that led to the depletion of fisheries in the past. Finally, the growth of aquaculture, or fish farming, may enable the production of fish in both developed and developing countries at costs that are lower than fishing in the open seas in a situation of declining stocks.

All these issues are intertwined. However, it is the failures of past government policy and how they have contributed to current problems that is a major theme of this monograph. In order to analyse the most important theoretical issues and policy questions, the discussion focuses on sea fisheries rather than rivers and lakes, and on the continental shelf and inshore resources more than the relatively barren high seas.

The tragedy of the commons

The concept of the ‘invisible hand’ was developed by Adam Smith, who explained how an individual who ‘intends only his own gain’ may be ‘led by an invisible hand to promote…the public interest’. Unfortunately, Smith provides very few examples of situations where this principle would and would not work, or criteria to explain this. However, in the case of resources such as fisheries, the notion has been heavily criticised, though perhaps unfairly.

Most famously, Hardin (1968) describes the ‘tragedy of the commons’ in which individuals acting in their own self-interest bring ruin to all. He uses the example of a pasture open to anyone who wishes to graze his animals there (stating later that the problem also applies to the oceans (ibid.: 1245)):

As a rational being, each herdsman seeks to maximize his gain. Explicitly or implicitly, more or less consciousl...