![]()

Chapter 1

Representation of female wartime bravery in Australia’s Wanda the War Girl and Jane at War from the UK

Jane Chapman

Introduction

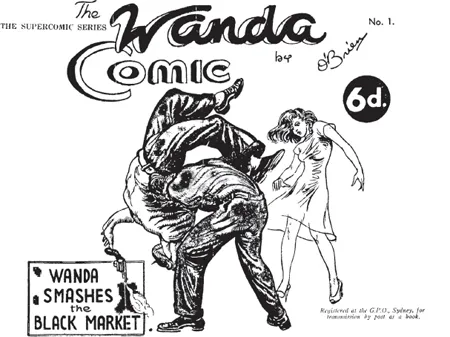

During the Second World War (WWII), one of life’s simple pleasures was to read the lift-out comics sections in the Sunday newspapers. Ruth Marchant James, a resident of Cottesloe in Perth, recalls that she could not wait to consume Wanda the War Girl, an Australian comic strip first published in the (Sydney) Sunday Telegraph in 1943, and later collected into two comic books (2007). A school history textbook about the period claims that Wanda was the first wartime Australian female icon: servicemen painted her picture on their tanks and planes and she was said to be Australia’s favourite pin-up (Ciddor 1998: 23). She escaped from espionage dangers involving German and Japanese armed forces, and her foolhardy exploits were often drawn from contemporary newspaper stories. After the war, her adventures morphed into detective-style escapades, and the glamorous, well-dressed heroine embarked upon dangerous exploits until the strip was abruptly terminated mid-adventure in 1951 (NLA 1984). Unfortunately, the locally produced comic could not compete with American imports.

Wanda the War Girl appealed to adults and was said to be more popular with children than Superman (Ciddor 1998: 23). Not only was Wanda beautiful and feminine, she was also a tough independent woman. Creator Kath O’Brien’s intention was ‘to give credit to Australian service girls for the marvelous job they are doing’. O’Brien recognized the changing social status and working lives of women. The overall effect of the strip was refreshingly different to the generally negative depiction of the sexualized woman in Australian war comics (Laurie 1999: 121). O’Brien was influenced by Black Fury, an early wartime comic in the Telegraph (drawn by another woman, American Tarpé Mills), and by Norman Pett’s extremely successful Jane, who appeared in Britain’s Daily Mirror. According to John Ryan, O’Brien’s illustrative style is one of the most original and individual styles to appear in Australian comics, and is reminiscent of the work of William Dobell (1979: 53). Eventually, the strips were collected into comic books published by Consolidated Press first as The War Comic and then as the first and the fourth in the Supercomic Series (1947–1950s) – the only original local products out of 66 US reprints (NLA MS 6514). After the war, O’Brien increasingly based her stories (written in conjunction with journalist C. W. Brien) on the novels of Ashton Woolfe, a self-promoting former employee of the French security services; she combined his (embellished) real-life accounts with items from newspapers.

Figure 1.

Wanda the War Girl was ‘one of the first comics to reflect a female point of view [and was] reflective of its period’ (Ryan 1979: 53). This chapter argues that Wanda the War Girl was a fresh type of female representation that differs from others during the period in both form and in substance. Wanda extended the scope and range of female comic-strip characters but she was also a sexually provocative pin-up who undoubtedly aided wartime propaganda.

Jane at War was even more sexually provocative, but this too was in furtherance of the war effort. She was a different type of female to Wanda: just as patriotic and brave, but a character whose good intentions were invariably accident-prone. When Jane, who worked as a spy, got into difficulty, her clothes were always central to the storyline because the scrape would entail her losing most of them. Thus fashion played an important part in the essential pin-up Zeitgeist. Clothes had to be fashionable, feminine, and carefully styled to display the character’s perfect figure and shapely curves, and, in contrast to Wanda, whose image was powerful, Jane’s underwear was the most essential part of her wardrobe. Jane’s creator Norman Pett was under much pressure to produce speedily and regularly for the British national tabloid the Daily Mirror. On one occasion he missed his deadline and had his contract suspended. After he had reached an agreement with the management, Jane returned and told her fans that she had been away because she had lost her pants. The newspaper office was then inundated with parcels from readers containing replacement undies, including one with a touching note from a 13-year-old girl, ‘Dear Jane, Perhaps these will help you out’ (Saunders 2004: 24). Unlike Wanda, who was created from O’Brien’s imagination, Pett’s drawings were constructed around regular poses by a real-life model, Christabel Leighton-Porter, who also gave stage shows for the troops during the war. She became a celebrity in her own right, but always posing as Jane, accompanied by a real dog (‘Fritzi’), identical to the comic-strip canine.

Context

It is generally accepted that if there had not been a war there would never have been an Australian comic-book industry (Gordon 1998: 10).1 This was due mainly to import licensing regulations and economic sanctions that restricted American imports during WWII: by 1948, the industry had grown to such an extent that there were 38 local and imported (mainly British) comic titles available each week (Stone 1994: 72; Ryan 1979: 197). However, when import restrictions were lifted, American products flooded the market again to such an extent that in the post-war period 80 per cent of comics circulating originated in the United States (Lent 1999: 22). Despite the heavy competition – or maybe because of it – the popular characters produced in local comics have a social significance as part of the nation’s cultural heritage.

Wanda the War Girl provided a newly progressive depiction of women, and as such, it mirrored both wartime representations and a new social trend that saw women leave the home in order to serve the war effort. Female Australian comic-book artists such as O’Brien shared a ‘strong commitment to giving a more balanced view of women in comics’ (Ungar, in Shiell (ed.) 1998: 79). This point is best explored by looking briefly at female representation before WWII.

In US comics history, the pre-WWII period is referred to as ‘The Early Industrial Age’ (Lopes 2009). This primitive label is reflected in the content of other Australian visual archives of the period such as cartoons where female depictions are somewhat unenlightened. John Foster points to sexism by omission and provides examples where no women appear at all, even as protagonists or assistants (1990: 18). In Bluey and Curley, when women do appear, they are ‘domestic tyrants who will not allow their male partners any pleasure or they are silly and frivolous’ (Ungar 1998: 70). Popular strips aimed at the adult market such as Bluey and Curley and Wally and the Major were set in male-dominated worlds, where female characters were often nameless – ‘Mum’, ‘Mrs Curley’, ‘Mrs Bluey’ – and who never seemed to leave the house.2 Comics theorists McAllister et al. point out that portrayals of life are not neutral or random (2001: 5): it is not coincidental, therefore, that when women were featured working, it was usually in jobs offering little opportunity for adventure. Most often, women appeared as honeytraps or as harridans (Minell 2003).

As Foster points out, 95 per cent of those who created comics were male and it was always assumed (during the wartime period at least; this changed in the post-war years) that 90 per cent of the readers were too. The adventure genre dominated and bravery centred on missions to create ‘peace and order out of the chaos produced by the forces of evil’ (Foster 1999: 145). Women’s roles were as damsels in distress, helpmates for the male protagonist, or victims. Historians of comics acknowledge that in wartime comics, women were usually depicted as civilian casualties, grieving relatives, and/or the victims of rape, pillage, looting or starvation (Stromberg 2010: 50). Up until 1939 women were not usually shown as members of the armed services, and WWII was the first time that Australian women were depicted in such roles. Wanda the War Girl reflected this change; as Joseph Witek suggests, ‘Art has a psychological need to hear and render the truth’ (1989: 114). This aspect of representation can also be seen in the US comics industry, where female characters assumed service roles in addition to becoming costumed superheroes (Robbins 1996).

Of course, stereotyping of women either as harridans or as honeytraps was not unique to Australia. Worldwide, the majority of characters depicted in comics have been male and the corollary of this seems to have been that most female characters have been categorized as virgin, mother, or crone (Stromberg 2010: 50). Women’s roles may, in fact, be further reduced to just two categories: either maiden/vamp or mother/old hag. The former are depicted as busty, physically exaggerated objects of desire – worthy only of rescue or ‘merely a beautiful token to be at the side of the male main character’ (Stromberg 2010: 136). Conversely, the mother/hag is usually ugly and dominates her overly domesticated husband.

Social realism

Roger Sabin has noted that American superheroes became patriotic figures fighting for their country – ‘unashamed morale-boosters’ – so why should a woman not also fulfill this function (1996: 146)? Unlike her American contemporary ‘Miss Lace’ in Male Call, Wanda did not just hang around the army bases like a ‘perpetual maybe’ (Stromberg 2010: 51) – that is, a female who may be sexually available. Wanda was a proactive adventuress/spy for the war effort, with the result that her representation was less patronizing than that of previous female characters.

Witek acknowledges that there is a recent tendency to connect ‘the textual specificities of the comic form to the embeddedness (sic) of comics in social, cultural, and economic systems’ (1999: 4). Certainly, war comics of a more masculine type published in the post-war period tended to have high levels of factuality and were often based on true stories. All the same, it is clearly not possible to obtain a rounded picture of the war period from comics. The social history of Australia, as it relates to women, has its limitations. The society that spawned comics in this period has since changed radically of course, and while, according to Foster, ‘no rounded view of the history is possible, however, simply because of the natures of both the medium and its readers’ (1999: 150–51), it is also true that comics provide ‘pieces of the mirror’ that can be assembled (1990: 22). Wanda’s wartime bravery reflects the new social and political realities that heralded a change in the attitude towards women.3 McAllister, Sewell and Gordon stress that ideology is strongly connected to issues of social power and Wanda, in this respect, is often ideologically contradictory (2001: 2–3). Yet, despite such limitations and contradictions, this particular strip has value as a social document because of its acknowledgement of the important role of the active servicewoman.

Pin-ups

It is true that Wanda was a voyeur’s delight, for her clothes were constantly torn – the better to display her long, shapely legs and impressive bosom. While she was more modest than her risqué English wartime equivalent, Jane, Wanda retained the suggestion of sex, albeit unspoken. It is worth noting that Wanda the War Girl was drawn by a female artist, and while she competed with Moira Bertram’s Jo (Jo and her Magic Cape), Tarpé Mills’ Miss Fury, and Dale Messick’s Brenda Starr, it was Wanda who became the most widely displayed Australian pin-up. The comic character Jane was also a huge success as a pin-up (Saunders 2004); and Wanda, like Jane, was a ‘truly national phenomenon and was seen as boosting the morale of the men in military service’ (Stromberg 2010: 50–51). Jane was credited as having helped the British troops to travel six miles into German-occupied France in just one day, following D-Day, when she finally shed all, rather than just some, of her clothes (Saunders 2004: 90–114): in fact, scholars have acknowledged that the pin-up can channel sexual energy by transforming it into a weapon as military energy (Kakoudaki 2004: 231). Both Wanda and Jane are the result of propaganda campaigns that encouraged men to idolize a particular sort of woman – the attractive servicewoman (Westbrook 1990: 587). In the face of a global conflict of unprecedented reach, governments needed to recruit women for the war effort which meant that the expansion of the role of women was inevitable. What was new in representational terms was that these ‘new’ women were sexy, powerful, brave and productive.

There were three main taboo subjects during the 1940s and 1950s for Australian comics: sex, violence and bad language. Kissing and passionate embraces in romance comics were permitted but ‘there was seldom any physical contact between the genders’ (Foster 1999: 145). Casual sex was considered risky, both to health and to national security. Indeed, in relation to the representation of women in the illustrative archives held by the National Archives of Australia, Minell comments:

Other female characters

Much of Wanda’s female competition was not quite as socially realistic. In January 1945 the Daily Mirror introduced another Australian cartoon strip by 16-year-old Moira Bertram, Jo and her Magic Cape: dark-haired Jo was beautiful and used her magic cape to help her boyfriend – an American pilot named Serge – to outwit gangsters, as well as the Japanese. The magic cape was a common trope – a comic-strip fictional device to speed up the narrative and herald action – but its fantastic nature detracted from Jo’s innate bravery and credibility. The strip ran for a few months before moving into comic books. Another local artist, Syd Miller (of Chesty Bond fame), in 1945 created a female character called Sandra for the Melbourne Herald. Although Sandra also appeared in England and elsewhere, Miller, according to John Ryan, found that a female character limited the type of stories he could present. Sandra was axed the following year to be replaced by the inimitable Rod Craig, an adventure strip that was adapted as a radio serial (Ryan 1979: 54). Comic creators believed that their male readership would not tolerate too many female characters because such characters slowed down the action. The relative scarcity of female characters meant that those who did appear were not only more likely to occupy traditional roles, such as mother or wife, but would be open to stereotyping. Martin Barker argues a form of mitigation against allegations of stereotyping, however, by stating that the comic form has an equalizing effect. This, he argues, should point theorists towards a slightly different line of enquiry:

Notwithstanding, there must be a relativist case to argue: ‘types’ of women impact upon cultural understanding of a far larger proportion of a country’s population than do those of plumbers. Clearly, the issue of representation within the comics form ...