eBook - ePub

Context Providers

Conditions of Meaning in Media Arts

Margot Lovejoy, Victoria Vesna, Christiane Paul, Margot Lovejoy, Christiane Paul, Victoria Vesna

This is a test

Share book

- 359 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Context Providers

Conditions of Meaning in Media Arts

Margot Lovejoy, Victoria Vesna, Christiane Paul, Margot Lovejoy, Christiane Paul, Victoria Vesna

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Context Providers an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Context Providers by Margot Lovejoy, Victoria Vesna, Christiane Paul, Margot Lovejoy, Christiane Paul, Victoria Vesna in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Sociología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

DEFINING CONDITIONS FOR DIGITAL ARTS: SOCIAL FUNCTION, AUTHORSHIP, AND AUDIENCE

A congruence of factors emerged in the last century that created conditions that broke down traditional concepts of art as object and forced the evolution of dynamic forms with new functions. These factors challenge authorship as well as relations between artist and audience in the construction of meaning, and they raise new questions about the relationship between theory and practice.

Once images could be captured by the machine eye, diverse ways of seeing and experiencing the natural world evolved along with methods of disseminating and transmitting them over distance into one’s home or work environment. The immateriality of these processes began to affect ideas about art as object in terms of time and space issues. Also, by the mid-twentieth century, it became clear that the computer’s capacity to process sonic, visual, or textual information as data objects created the potential for a vast new multidisciplinary direction for art. Data could be endlessly manipulated and stored in databases or archives to be called up for a myriad of uses within numerous contexts and disciplines, especially with regard to long-distance communications. These technological changes allowed for interactive exchange and participation to take place within an artwork, thus changing a work’s potential form and function. In the context of the cultural developments that have emerged as a result of these major changes in technological standards, a new consciousness has evolved in which art as an object for individual viewing became more and more challenged. Not only had the artwork become immaterial and interactive, but it could be seen or experienced simultaneously by mass audiences in different locations. Although harnessing the creative process is still the artist’s essential task, the loss of full authorship control in creating a digital work has become a reality for those artists who seek to create self-generating forms that allow for significant levels of participation and agency.

In the context of the early twentieth century, artists were already interested in the phenomenon of powerful, invisible, immaterial natural forces being discovered in science, such as electricity and the X-ray. Artists such as Marcel Duchamp and Alfred Jarry attended public lectures on these scientific discoveries, which they interpreted in their own way. Later, composer, philosopher, artist John Cage’s explorations of hidden dynamics led to witty experiments with the randomness of chance operations. In the 1960s, the work of artists interested in happenings, performance, environmental works, sound, video, and independent film as well as new forms of public art led to the expansion and acceptance of the idea of art as an immaterial concept. Some of these interdisciplinary early forms had direct participatory aspects. A relationship began to grow as early as the 1940s between independent filmmaking and the use of projection in room-sized installations as experiments with time and space. The use of the film projector in these conceptual works was essential. This tendency led to the acceptance of the new medium’s use as spatial installation forms by early video artists, such as Joan Jonas and Bruce Nauman, in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The simultaneous growth of the European Zero and Grav movements in the 1960s and 1970s with the art and technology movement in the United States created further acceptance of the use of technology in art making. With the widespread arrival of digital technologies at the turn of this century, new levels of participation and interpersonal communication have been achieved and have further emphasized the tendency through the use of media toward immaterial virtuality and the loss of the traditional object as art. Installations making use of multiple aspects of projection and sound have shifted the “white box” space of the gallery toward the “black box” of the movie theater. The complex potential of these artworks now often calls for interdisciplinary collaboration between visual and performance artists, programmers, designers, and musicians.

Audience and authorship

“Interactivity,” a keyword used to describe the digital, has become so loaded with meaning that it is by now virtually meaningless. It has been used to describe anything ranging from point-and-click navigation—a monologic approach—as opposed to an open dialogic system that creates the opportunity for a fully collaborative dialogue to take place. Although dialogism in electronic media is interactive, it should not be confused with the potential for collaborative exchange provided by telecommunications-based artworks that interactively make use of global network connectivity. In such open works, the artist’s intention is to introduce an audience to go beyond the type of interpretation expected of traditional work. The construction of digital artworks is specifically dedicated to create a desire for collaborative exchange with a wide public where the exploration of experiences in time and space has the potential to release new insights.

Russian philosopher and literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin’s ideas intersect with the new media debate about interactivity (Holquist 1981). Writing in the early years of the twentieth century, he is one of the first to focus and explore the meaning and structure of dialogue as a collaborative rather than individual force. He believed that our individual acts of expression—whether visual, written, or oral—are the result of dynamic, difficult inner struggle, which may sift through one’s social knowledge to experiences with others’ dialogic interconnection or cooperative exchange.

Because digital media are often literally dialogic (as opposed to a dialogue that configures itself as a mental event), the position of “making” and the relations between artist and audience are altered. Their roles and identities are changed. The experience of the traditional art object is in the transposition from the look of the eye to the eye of the mind. All arts can be called participatory if we consider viewing and interpreting a work of art as reaching an understanding as part of a communicative monologic dialogue. In interactive digital works, however, the interface meeting point between artwork and viewer becomes an interplay between form and dialogue, similar to that which Bakhtin located in literature—that is, “stratified, constantly changing systems made up of sub-genres, dialects, and almost infinitely fragmented languages in battle with each other.” Such collaborative systems, with their inherent contradictions, are a force for forging new unpredictability in aesthetic territory in a process Bakhtin termed “the dialogic imagination” (Holquist 1981).

In this process the role of the artist/author changes from one who has total control of the artwork to one who designs a “framing” or “ethnographic” structure that invites a wide public to collaborate. Without audience participation, the work is incomplete. However, as Sharon Daniel points out in her essay, “interactive” systems sometimes obscure the relation of “user” input to system output. In addition, the prefix “inter” suggests a “between” that can be erased in digital arts, which sometimes collapses boundaries to a point where the elements and parties between which a communication was established merge into one system.

Digital technologies change the nature of interaction itself. Digital functionality—such as algorithmic calculations, databases, and telecommunications—transform a work of art into a dynamic environment. Here, viewers become participants in a space that is unlimited by clearly set boundaries, with the potential for the emergence of new events and insights that unfold as an active collaborative process. [Fig. 1.i.1]

The term “interdisciplinary,” also often used to describe a defining characteristic of the digital medium, raises similar questions. The connection between disciplines—aspects of the visual and performing arts, the humanities and social sciences, science and information theory, to name just a few—certainly plays a role in defining the dynamic nature of digital arts. New media works often are a product of complex collaborations between visual and performance artists, programmers, scientists, designers, musicians, and others. But the roles in this collaboration can range from that of a contractor or consultant to a full-fledged collaborator. Also, boundaries between disciplines are often erased, leading to a new form or field, or making a work equally important in the context of each field, such as art and/or science.

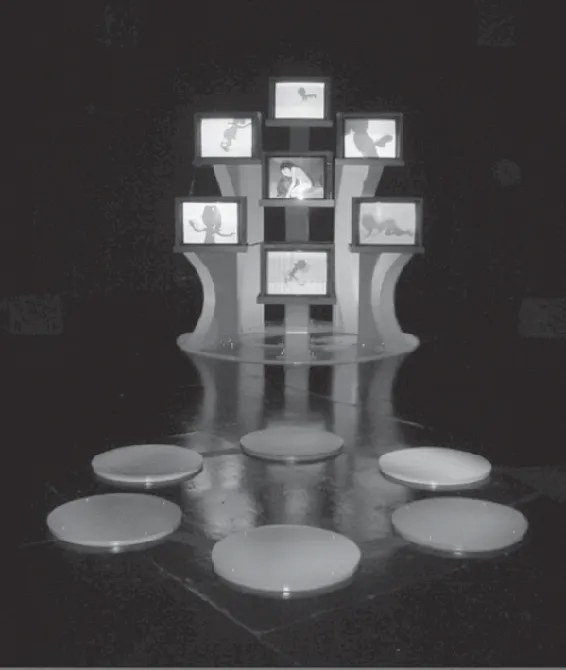

Figure 1.i.1 Marina Zurkow, “Nicking the Never,” 2004, Interactive 7 DVD channel Installation, The Kitchen, New York, N.Y.: Design/Construction: Palmer Thompson-Moss; Technology: Julian Bleecker; Music: Lem Jay Ignacio. Photo by David Anderson / DaxoPhoto.

The viewer walks the wheel on the floor, mapping the character’s interior dramas as a play on our own less manifest relationships between body, emotion and the projected imagination. “Nicking the Never” enacts the Wheel’s states of selfhood through her physical gestures and surreal circumstance in a series of looping narratives. The work translates the Wheel’s psychedelic and lurid aesthetic into a personal language, rife with graphic and cartoon styles and the tropes of Western psychology. As a pop, subjective interpretation of the ideas and iconography of the Wheel of Life, “Nicking the Never” is in dialogue with this vivid world-view. (Courtesy Marina Zurkow)

Navigation and process, as well as the creation of meaning in an environment without fixed entry points and hierarchies are among the issues that challenge traditional ideas about art. The common cultural desire has been to classify artworks as “objects.” But in the creation of dynamic media works, the artwork becomes a project with openness for play and agency in which the artist tends to become a mediatory agent. Such a work now essentially depends on the grounds for communication that are constructed—and on the boundaries and poetics of control established through interface and navigation structures. However, the rapidly changing conditions of where and how a dialogic work is accessed and processed raise significant questions about the shifting relations between context and content. These shifts are addressed by the differing perspectives on aspects of representation and the creation of meaning throughout Part One of this book.

Given the phenomenal influence of Gilles Deleuze’s writings (1953–1995) on culture, a phenomenon that has become known in France as the Deleuze effect, it is not surprising that many of the essayists in this book also refer in various ways to his influential philosophical meditations. His orientation lies away from the common sense logic of philosopher Immanuel Kant but toward seeking and finding unforeseen directions. His is a map “meant for those who want to do something with respect to new uncommon forces, which we don’t quite yet grasp, who have a certain taste for the unknown, for what is not already determined by history or society” (Rajchman 2000: 6). His concepts seem to fit the instability of the times when there is a blurring of boundaries due to the “electric shocks” we are experiencing in every field. Deleuze’s tendency is to position philosophy as a “reservoir from which each person could draw what he or she wanted… as an encounter” (Rabouin 2002, personal communication).

Although spectator participation had been theorized by Fluxus performance, happenings, and in work influenced earlier by Duchamp and Cage, Nicholas Bourriaud introduced in Esthétique Relationnelle (Bourriaud 1998), the phrase “relational aesthetics” to describe “a process-led, socially aware approach to audience/artwork relationships.” Relational aesthetics is meant to describe process-led, socially aware, tangible models of sociability as the current approach to audience/artwork. He comments about art history: “In the beginning art dealt with Humankind and deity; and then between Humankind and the object; artistic practice is now focused upon the sphere of inter-human relations as illustrated by artistic activities since the early 1990s. So the artist sets his sights more and more clearly on the relations that his work will create among his public, and on inventions of models of sociability” (Bourriaud 1998: 28). [Fig. 1.i.2]

New media technologies challenge the way narrative forms of expression can be developed through dynamic experimentation. In their catalogue for an exhibition titled “Future Cinema,” curators Jeffrey Shaw and Peter Weibel comment that among the multiplicity of modes, three narrative types stand out as being central. Transcriptive forms involve multiple layering of interactive narrative that can create loops and the reassembly of narrative paths. Recombinary permutation strategies are controlled by the algorithm that defines the artistic definition of each articulated work. Distributed forms grow out of the modalities of Internet telecommunications accessible on mobile phones or multiuser devices. These become social spaces, so that the persons present become participants in a set of narrative dislocations.

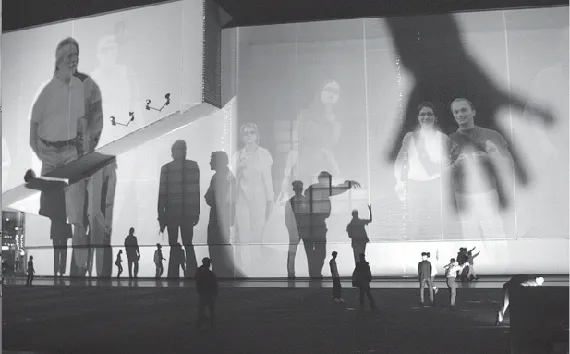

Figure 1.i.2. Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, “BODY MOVIES: Relational Architecture 6,” 2001–2003. Installed in public squares in Europe: Rotterdam; Lisbon; Linz – Ars Electronica; Liverpool Biennial; Duisburg. With the assistance of six developers.

This project transforms public space with 400 to 1800 square meters of interactive projections. The public effect is to invite anyone entering the square to communicate within the playful, phenomenological light and shadow relational environment. Thousands of portraits taken (on the streets of the cities where the project was exhibited) are shown using robotically controlled projectors. However, the portraits appear only inside the projected shadows of local passers-by, whose silhouettes can measure between two to twenty five meters high, depending on how far people are from the powerful light sources placed on the floor of the square. A custom-made computer vision tracking system triggers new portraits as old ones are revealed. (Courtesy Lozano-Hemmer)

Sound tracks have become integral to most of such new media works and introduce a new flux and momentum to them as a vibratory, immaterial, shimmering element that may integrate many different connected elements within contemporary installation projects.

Agency and social function

In an artwork as “open system,” exchange leads to agency, a place where negotiation takes place as a form of shared authorship and social exchange. In their essay, Kristine Stiles and Edward Shanken maintain that agency is implicitly the primary goal and meaning of interactive multimedia art. If one of the functions of multimedia is agenc...