![]()

Chapter 1

Cartelisation in Sweden?

Magnus Hagevi and Henrik Enroth

On Saturday, 27 December 2014, six people called an urgent press conference. They were the party leaders of the main adversaries in Swedish politics – the Social Democrats on the left and the Moderates on the right – and their respective allied party leaders in the competing left- and right-wing blocs. They announced their agreement to form what amounted to a cartel, the so-called December Agreement (Bäck and Hellström 2015).1 Because of the success of the populist radical-right Sweden Democrats in the general election earlier that year, neither of the two political blocs had gained a majority of the parliamentary seats. The main intention of the agreement was to exclude the Sweden Democrats from political influence and to maintain the two-bloc system as the basis for cabinet-formation (Bäck and Hellström 2015: 272). The agreement had little of substance to offer except this: the largest established political blocs would form the government and the government budget bills would win the final vote in Parliament.

Given the collaboration between the established parties and the lack of policy substance in the resulting agreement, this unprecedented event might seem an open-and-shut case of party cartelisation, as stipulated by the influential yet contested cartel party theory of Richard Katz and Peter Mair (Katz and Mair 1995) – albeit that, in this case, the point of the cartel was not so much to reduce party competition tout court (cf. Mair 2007) as to ensure continued bipolar competition in the Swedish multi-party system (Bäck and Hellström 2015).2 However, as critics of the cartel party theory have pointed out, cartels in general are inherently unstable and vulnerable to defection by those who have the least to gain from staying in the cartel (Kitschelt 2000: 168; cf. Blyth and Katz 2005: 39; see also Chapter 2 of this book). Indeed, in a delegate rebellion against party leadership, the smallest right-wing party, the Christian Democrats, voted down the December Agreement during a party congress in 2015, setting off a domino effect that led the other right-wing parties to swiftly defect from the agreement as well.

Far from supporting the cartel party theory, then, in point of fact this cataclysmic event in Swedish politics constituted a high-profile cartel failure, one that calls into question Katz and Mair’s claim that the Swedish political system would be especially conducive to cartelisation (1995: 17). If anything, the break-up of the December Agreement suggests the need for a systematic assessment of the cartel party theory, empirically, theoretically and normatively. This book seeks to provide such an assessment.

For two decades, the cartel party theory has been a strong and controversial presence in the field of party research. According to the theory, political parties in Western democracies have come to function ever less as channels into the state for constellations of interest and identity in society and ever more as professional organisations in the state whose prime interest is organisational survival. Rather than bridging the gap between state and society, Katz and Mair suggest that political parties have, instead, widened the distance between them to a point where the party as an organisational form has been incorporated into the state.

The cartel party theory consists of two interrelated hypotheses (Katz and Mair 2009: 756–7). The first hypothesis is that parties are becoming increasingly removed from civil society and instead are converging with the state (Mair 1994: 7–8), which encourages or forces them to co-operate with one another. This change is leading to parties becoming dependent on public party subventions, effectively making the parties a part of the state (Katz and Mair 1995: 15, 2009: 754–5, 759), while party members, as representatives of civil society, are in practice becoming rationalised out of existence (Mair 1997: 113–4; Katz 2001; Katz and Mair 2002; see also Panebianco 1988: 220–35). The second hypothesis is that the parties are developing common, similar and sharply constrained policies (see Blyth and Katz 2005). The most significant change is said to be that parties are becoming increasingly alike. The pressure to transform should, according to these scholars, entail the levelling-out of differences between how parties manage the polity.

Even as the originators of the cartel party thesis were calling for studies to test their ideas (Katz and Mair 2009), other scholars were scrutinising the same ideas and criticising the thesis as vague and difficult to confirm (Koole 1996; Widfeldt 1997; Kitschelt 2000; Hopkin 2004; Detterbeck 2005; Scarrow 2006; Loxbo 2013, 2014a; Kitschelt and Rehm 2014; Enroth 2014, 2017; Hagevi 2014c). Despite the lack of empirical studies of cartel parties and cartelisation, the notion of the cartel party as a typological successor to the ‘catch-all’ party – a type of party seeking to appeal to a large and diverse segment of voters by way of general and vague policies (Kirchheimer 1966) – seems dominant in current party research. The engines of change, according to the cartel party thesis, are parties’ increasing dependence on state party subsidies to pursue and manage the polity (Pierre, Svåsand and Widfeldt 2000; Gidlund and Koole 2001; cf. Koß 2011); dependence on the mass media for political communication (Strömbäck 2009); and social changes, primarily economic globalisation (cf. Loxbo 2014a). As a result of these, according to the theory, parties perceive their latitude to pursue policy and engage in representation is shrinking (Blyth and Katz 2005; Katz and Mair 2009; Mair 2009, 2013; Katz 2014).

While the cartel party theory has been the target of a good deal of critical commentary in academic journals since it first burst on to the scene, the theory has not yet been subjected to systematic empirical and normative assessment in a single book. Such attention is long overdue, as the theory remains dominant in research on parties and party systems and its authors have continued to work on and defend it. Most recently, Peter Mair’s posthumously published Ruling the Void (2013) reiterates the basic tenets of the cartel party theory. The present book is based on an extensive empirical investigation of the Swedish case, which the authors of the cartel party theory have themselves presented as a critical test: if cartelisation is going to happen anywhere, the theory suggests, it should be evident in the Swedish party system (see Katz and Mair 1995; cf. Blyth and Katz 2005). By the same token, to the extent that this is not the case, it is less likely that cartelisation would be found in other political systems with circumstances relatively less favourable to it.

The aim of this book, therefore, is to assess the cartel party theory based on a study of the Swedish party system, specifically, the party groups in the unicameral Swedish Parliament (the Riksdag). Attending to a range of factors, we ask whether or not the party groups in the Riksdag have increasingly come to resemble one another in the period from the late twentieth century to the first decade of the twenty-first century. This is an important and original contribution to current research on changes in parties and party systems. Most existing studies are comparative surveys of general trends, whereas this book investigates the causal mechanisms that are expected to foster cartelisation, through a critical case study. Our study focuses on everyday parliamentary politics, not extraordinary events such as the December Agreement. Our data were systematically collected during the period when the proponents of the cartel party theory claim that cartel parties emerged (Katz and Mair 1995). Before we turn to the contents of the subsequent chapters, let us take a closer look at the Swedish case as a testing ground for the cartel party theory.

THE SWEDISH CASE

In Swedish politics, the originators of the cartel party thesis and their followers have noted a number of characteristics that, they argue, would facilitate cartelisation. Sweden has been a stable democracy since the 1920s (Möller 2015). Scholars regard political parties as strong and pivotal actors in the Swedish political system, including in Parliament (Isberg 1999; Hagevi 2000a; Detterbeck 2005). As in all proportional electoral systems, Swedish voters focus on parties (Oscarsson and Holmberg 2013; Hagevi 2015a). The parties are vital in the careers of politicians (Petersson et al. 1997; Hagevi 2003; Öhberg 2011; Isaksson 2006; see also Chapter 4 of this book); they suppress alternative ways of aggregating interests in society (Hermansson 1993); and they are becoming increasingly important in the public sector (Wallin et al. 1999). Several studies report that public party subsidies are replacing both the financial and internal democratic significance of party membership (Katz and Mair 2002; Borchert 2003; cf. Pettersson et al. 1997; Isaksson 2006; Hagevi 2014b; see Chapter 3 of this book). Also, Swedish parties have received substantial party subsidies for a very long time, in an allocation system that they control themselves (Gidlund 1983, 1985; Wiberg 1991; Gidlund and Koole 2001; Hagevi 2003; Koß 2011). Swedish politics has also long been characterised by consensus-seeking actors in a system in which agreement and compromise are embedded in the political culture (Tingsten 1966; Uddhammar 1993; Hadenius 2008; Möller 2015; cf. Arthur 2010), conditions expected in the theory to facilitate cartelisation.

With respect to distinctive national characteristics, several scholars have linked the cartel party thesis to the greater political dependence of individual countries on international conditions (Blyth and Katz 2005; Katz and Mair 2009). Here as well, the Swedish case favours cartelisation, because Sweden has been a member of the EU since 1995 and the Swedish economy has been strongly internationalised for a very long time (Ekholm 2000; Sandelin 2005).

The Swedish population is ten million. Politically, Sweden is a unitary parliamentary state with general elections (by proportional representation) held every fourth year (between 1970 and 1994, every third year). At the same time as parliamentary elections, citizens also elect representatives to 21 regional and 290 local (municipal) assemblies. A large proportion of welfare state policies are implemented at the regional and local level. As well as the Swedish Parliament, the municipalities and regions also have the right to levy income tax. As is the case with all EU Member States, elections to the European Parliament are held every fifth year.

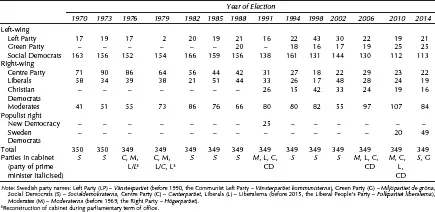

The Swedish party system was long entrenched as a typical Scandinavian five-party system (Lipset and Rokkan 1967). However, previously strong social cleavages and party identification have now weakened considerably among Swedish voters (Oscarsson and Holmberg 2013: 69–103). Since 1988 the party system has gradually fragmented, giving the eight-party system of today. In 1988 the Green Party first gained parliamentary representation; it lost representation in 1991 and regained it in 1994. In 1991 the Christian Democrats and New Democracy first gained parliamentary representation; New Democracy, a populist right-wing party, lost its representation in 1994. In 2010 the Sweden Democrats, a radical populist right-wing party, first gained parliamentary representation. Government formation in Sweden is heavily dominated by the divide between the right-wing (Alliansen) and left-wing (De rödgröna) blocs. These two blocs have a half-century-long history but, in recent decades, the number of parties within the blocs has increased and the names of the blocs have changed (Aylott 2011: 314; Hagevi 2015b: 79). The Swedish government has generally been formed either by social-democratic prime ministers (mostly one-party minority cabinets) supported by left-wing parties or by right-wing parties (mostly multi-party coalition cabinets). Since 1991 the Social Democrats, the Green Party and the Left Party have formed the left-wing bloc, while the Moderates (belonging to the conservative parties of the European party families), the Centre Party, the Liberals and the Christian Democrats have formed the right-wing bloc. No populist right-wing parties, such as the Sweden Democrats, have formally joined either of the two political blocs. In recent decades, the major political adversaries and competitors for the post of prime minister have been the party leaders of the Social Democrats and the Moderates (Möller 2015). Table 1.1 shows parties in cabinet and distribution of seats in the Swedish Parliament, by party, since 1970.

The studies in this book are oriented mainly towards the party groups in the Riksdag, where the parties are the main actors (Hagevi 2000a: 145). Party cohesion is strong: when MPs vote in Parliament, they cast 99 per cent of their votes along party lines (Staberg 2000: 32). Public policies are formulated within parties by their MPs, who are at the centre of cartelisation. Swedish MPs report extensive interaction with the various faces of the parties – that is, the party on the ground, the party in central office and the party in public office (Hagevi 2000a) – and MPs are therefore at the centre of any possible cartelisation. The MPs are dependent on the party members in their constituencies for renomination to the ballot (Johansson 1999) and for the possibility of re-election by voters.

In parliamentary systems, a parliament can be categorised as mainly deliberative (like the British Parliament) or as a working parliament, of which the Swedish Parliament is a good example (Hagevi 2000b: 243–7). In working parliaments, the strength of parliamentary committees – the ability to influence the outputs of parliament – is important (Shaw 1979: 394). Several studies in this book recognise the importance of committees and make use of this knowledge (see Chapters 3 and 5 to 7 of this book). The absence of a single majority party or a majority coalition of parties has made minority cabinets usual in Sweden (Strøm 1986, 1990). During deliberation in committees, majority voting coalitions are sometimes formed by negotiations between MPs from different parties (Sannerstedt 1992; Sjölin 1993; cf. Chapters 3 and 5 of this book). It is important to note that party discipline is still effective in committees: MPs represent their parties in the committees and do not act as individuals (Sannerstedt 1992).

Table 1.1 Distribution of Seats in Swedish Parliament by Party, and Parties in Cabinet, 1970–2014

The Swedish Parliament has fifteen standing (permanent) committees (in Swedish, utskott; between 1970 and 2010 there were sixteen standing committees), each with seventeen MPs as committee members (appointed by Parliament to serve throughout the term of office).3 Committee membership is proportional to the number of MPs from each party. All bills must be deliberated on in committee before being voted on in Parliament. It is impossible to kill a bill in committee: the committees must always, after deliberation, adopt a position in a committee report and send it to the 349 MPs for a final decision in full session. Views deviating from the committee majority are included in the committee reports as reservations. In virtually all cases, the final decision made in the parliamentary session is the same as in the committee (Hagevi 1998: 51–2). In addition to the standing committees, other committees (in Swedish, nämnd) have other types of roles. One of them is the European Union (EU) Affairs Committee (EU-nämnden). Ahead of meetings in the European Council or the EU Council of Ministers, the Prime Minister and all cabinet ministers must gain support for their policies from the majority of MPs in the EU Affairs Committee, though the government’s propositions are not formalised in the same way as ordinary government bills in the standing committees and the positions of the committee are not put to parliamentary vote in full session. Because of this, the committee reports are somewhat different from the reports of standing committees (see Chapter 5 of this book).

CONTENTS OF THIS BOOK

In the rest of this book, six empirical studies of the Swedish case highlight various factors that the cartel party theory takes to be conducive to cartelisation, and discuss countervailing forces as well (Chapters 3 to 8). We explore whether party elites are becoming increasingly alike and increasingly removed from grassroots and constituents due to processes of professionalisation; whether opposition to government is waning in the wake of globalisation and Europeanisation; and whether parties are becoming more alike by adapting to general processes of mediatisation in politics. Chapters 7 and 8 investigate key factors not yet sufficiently acknowledged either by authors or critics of the cartel party theory: gender representation and party culture; we ask whether these factors act as countervailing forces to cartelisation. In the concluding Chapter 10, we discuss how the empirical results presented here might lead us to rethink accepted ideas about cartelisation, convergence and increasing similarities among parliamentary parties.

Chapter 2 provides a conceptual analysis of the cartel p...