![]()

CHAPTER 1

AN INTRODUCTION TO OPTIMAL RATIONALITY

Although optimal rational positions (ORPs) represent real requirements for change, people do not always modify their behaviour to match what ORPs suggest should be done. Given that the pursuit of ORPs is likely to lead to long-term positive outcomes, does this mean that people are behaving irrationally? Or do we need to rethink our understanding of what counts as rational behaviour and, as a result, help people act more regularly in more beneficial ways? Assuming that the second of these possibilities is most likely I use this chapter to explore the concept of optimal rationality (OR). OR provides a framework for considering the choices people make. Vitally, however, OR also provides an alternative to popular conceptions of rationality that have so far failed to provide a basis for tackling those issues identified by ORPs.

One commonly used model of rationality that OR can be compared against is rational choice theory (RCT) (e.g. Green, 2002; Sen, 1990). A form of economics-based rationality, RCT has an underlying premise of methodological individualism. According to this premise, people’s behaviour is characterised by their seeking to maximise the benefits (utility) and minimise the costs of pursuing a given goal (Green, 2002). As a consequence, individuals deliberate about the results of their actions according to how desirable these results are exclusively for themselves (Rose & Colman, 2007). While popular, RCT is subject to substantive critique. In particular, from studies that suggest individuals do not behave in ways that regularly and consistently maximise their benefits.1 For instance, people often make do with ‘good enough’ solutions as opposed to optimal ones; they use short cuts and rules of thumb rather than seek out all the information required to achieve maximal utility; and people can rely on intuition or perception rather than analyse the data relating to their decisions (Bilalić, McLeod, & Gobet, 2008; Kahneman, 2003). Vitally however, people also typically exhibit bounded will power: individuals may engage in ways that are totally inconsistent with what will objectively serve them best in the long term (Jolls, Sunstein, & Aler, 1998). Similarly, people act with bounded self-interest: that is, they act and care about others, so sacrifice or limit the maximisation of their own interests (Jolls et al., 1998). An extension of the idea of bounded self-interest is that people can also actively ‘team reason’ and seek to maximise collective rather than the individual utility (Rose & Colman, 2007).

OR in contrast to RCT is grounded in philosophic rather than economic notions of rationality, in particular it is informed by the work of both Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) and Aristotle (384 BC–322 BC).2 As a result, OR has a number of very specific characteristics: first and foremost OR is based on an acceptance of the Kantian idea that effective action can be determined if we apply reasoned argument to evidence: this is the very basis, in fact, of an ORP. At the same time OR rejects Kant’s suggestion for how to ensure people act in ways believed to be effective: his notion of the universal moral imperative. A moral imperative is something that tells us uncategorically how to behave and is typically signalled by the presence of an ‘ought’ (Scruton, 1982). Moral imperatives are thus something we are intuitively drawn towards, knowing that they are right – that we should (i.e. ‘ought’) to do them. While accepting the idea that moral imperatives can emerge from reasoned evidence-informed arguments – as noted in the introduction, ORPs contain a should-type statement – OR rejects any universal nature of what seems right. This rejection has, first of all, a spatial/temporal basis since any position that seems universally correct now is simply right for a given place at a given point in time (Latour, 1987). Second, a universal moral imperative, as its name suggests, is an imperative that we all agree on. While there are certainly beliefs that hold across individuals and societies, given the strongly held positions of certain groups it seems likely that for any ORP there will be some who do not agree with it (Latour, 1987; Nozick, 1974; Williams, 1981). Some might disagree because the requirements of an ORP represent a clash of values. Others, however, may believe that the changes represented by the ORP will be disadvantageous to them: indeed, history is littered with groups with vested interests – for instance tobacco firms and car manufacturers – who have funded research studies with findings that suit viewpoints counter to ORPs (Evans, 2017).

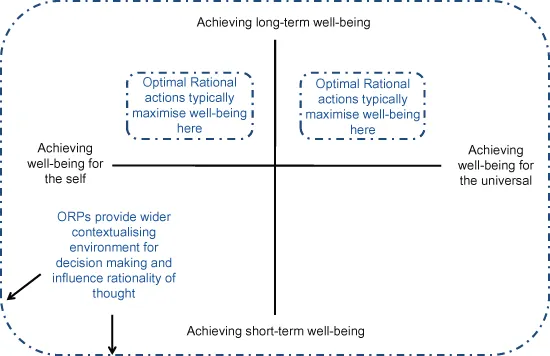

OR is also informed by a repositioning of Aristotelian reasoning, which suggests that rationality may be exercised in two ways: theoretically and practically. In other words, the argument that rationality can occur both in terms of how we think and what we do, with these forms of rationality existing separately and both being equally valid. While accepting this division between what we think (or know) and what we do, OR departs from key aspects of Aristotle’s position in three key ways. First, OR is grounded in the idea that in modern Western societies we more or less have the freedom to choose how we act and behave. However, whereas Aristotle simply considers the activities at which people might direct their efforts in order to achieve happiness, OR considers the ‘what we do’ form of rationality in terms of both time and with regard to who might be affected by our actions. This is because OR argues that we can conceptualise and judge rational acts in terms of both when the result of actions are likely to materialise and who they will benefit or impact. The impact of rational acts thus ranges on the one hand from the individual (i.e. acts mainly benefit oneself rather than anyone else) to the universal (i.e. acts can lead to impact that benefits society as a whole) and on the other from short-term behaviour to that which also has benefits in the long term.

Second, while Aristotle considers virtue, OR argues that, whether in terms of when or who, in all cases rational behaviour is that which is concerned with achieving ‘wellbeing’. This does not mean, however, the type of utility maximisation postulated by models of rationality such as RCT; instead OR suggests that acts to enhance well-being represent what individuals ‘know’ are ‘needed’ at a given point in time. Thus, while sometimes our day-to-day actions represent short-term responses to immediate needs, because they are designed to achieve a required state of well-being, they can nevertheless be regarded as more rational than acts that achieve greater well-being in the longer term, if this short-term well-being is considered by an individual to be more necessary. It is also clear, however, that only focusing on the short term can have detrimental longer term consequences. For example, an individual may decide to get drunk each evening to satisfy a short-term need, without considering or ignoring what impacts this might have for their longer term well-being, i.e. the serious health and social problems that arise from continuous drinking. These issues also ultimately have wider societal impacts, leading, for instance, to further pressure being placed putting on health services.

That our actions have wider consequences both for the long-term self and for others leads to the third departure from Aristotle. Although people have agency – we are free to choose what we want to do (e.g. Sartre, 2013), what we think about our potential and actual actions is framed by societal and cultural norms and beliefs: there are ways of thinking and behaving that are more and less preferred and viewed as more or less acceptable (Nozick, 2001; Petrarca, 2008; Saint Augustine, 2002). It is against these that we judge our behaviour and against which our behaviour is judged. This provides a situation in which we can do what we choose but we also know more generally what is considered to be the ‘right thing’. Correspondingly OR incorporates within it society’s role in imparting and instilling into individual’s evidence, arguments and imperatives in order to provide a wider milieu within which their actions play out and are contextualised. This societal role may be thought of as providing normalising markers of what are considered to be appropriate – or good – behaviours which in turn establish a theoretical yardstick of reason against which people can judge their actions. It is clear then that ORPs, such as those detailed in the Introduction, can provide us through ‘rationality of thought’ a form of Kantian moral imperative: their purpose is to steer our thinking and so therefore our actions towards particular preferred paths that tend to objectively maximise welfare (i.e. welfare for everybody including ourselves, most typically in a period covering the longer term). Of course, not everybody will understand an ORP as representing the right thing, and ORPs can be rejected by some individuals and groups. Furthermore, because we are free to choose our actions we may not always act in conjunction with an ORP even though we know that doing so is the right thing to do, most often because an alternative may be more immediately appealing. When effective, however, OR positions serve to provide those checks that make sure we regularly engage in behaviour such as recycling and turning water taps and lights off, that we use hotel towels more than once, that we don’t fly too often or offset our emissions when we do, that we exercise more or, in the example above, that we drink in moderation.

In summary, this refashioning of Aristotelian and Kantian rationality leaves us with the situation depicted in Figure 1.1: rational behaviour can be separated into thought and deed, individual and universal, long and short term and can involve achieving welfare across these. ORPs relate to maximising well-being in relation to a specific combination of these aspects of rationality; specifically, ORPs relate to well-being for the long-term self and/or the long-term universal. Individuals, while knowing about ORPs may not necessarily or regularly act in accordance with them if they perceive other needs to be greater or that, at a given point in time (e.g. in the short-term), other actions are likely to deliver them higher levels of welfare. Alternatively, if they do not subscribe to it, individuals or groups may reject an ORP and pursue an alternative path. An OR outcome on the other hand occurs when individual pursues their desires they do so in ways congruent with approaches suggested by ORPs, which ultimately involve maximising overall welfare. For example, revisiting the example above, drinking one drink each night will prove a better way to balance long- and short-term welfare than drinking four or five. Similarly eating more fruit and vegetables and less cakes and sugar will also keep us healthier in the long run, while balancing the joy we may gain from consuming the latter. In other words, in such situations we moderate our behaviour so that if we (for example) eat cake one day, then for the next few days we don’t in order to even out our actions and achieve a short- and long-term welfare balance. By recognising that abstaining can be a positive way to maximise welfare, engaging in it to bring ourselves into line with an ORP thus becomes a rational act, even if we have a short-term need to eat cake or drink more beer. In such cases our welfare is derived from recognising the dis-benefits of serving that need versus the benefits to us longer term.

Figure 1.1. An Overview of Potential Rational Behaviour.

In other cases such as recycling, the notion of the welfare of the individual becomes much more integrated with that of the collective.3 Our short-term welfare reward for such action is often the understanding or recognition that we are doing something good (what Andreoni, 1990, describes as the ‘warm glow’). Although we might not tangibly feel the short-term benefit (and indeed the walk to the recycling centre might be a bit of a drag), this is offset by recognising that we are contributing to a more sustainable environmental future for everybody – both now and moving forward. In this sense, the nature of OR is harmonious with the highest levels of Aristotelian happiness. This is because it may well take some individuals a great deal of mental and or physical effort to actively moderate their behaviour to move beyond acting in more short-term and individualistic way to feeling satisfied with a ‘warm glow’ reward that comes from acting regularly to drive longer term and collective welfare (Aristotle’s notion of training virtuous behaviour). At the same time this work differs from thinkers such as Plato, Aristotle, Petrarca and Kant in that it accepts as reasonable that we often wish to pursue short-term pleasures. Nonetheless despite recognising the rationality of short-term self-interest, my aim is to help people pursue more optimal solutions when and where possible, since these are more beneficial long term, both personally and for society.

Understanding that sometimes individuals may know about ORPs but not engage in actions that cohere with them or may be rejecters of ORPs also help us to begin to consider the notion of ‘rationality gaps’. Returning again to the example of human-led climate change, according to a 2017 report by Leiserowitz and colleagues, almost 6 out of 10 Americans are worried about climate change. The level of climate change denial meanwhile stands at 6%. These figures are at the same level as they were in 2012, which suggests that the US public is relatively well informed about the risk and reality of climate change as well as the need to reduce its likely impact: in other words, the ORP I established in the introduction tends to be acknowledged by the public. Yet while 4 out of 10 Americans think the odds that climate change will cause humans to become extinct are 50% or higher, and 7 out of 10 think it will harm future generations of people and plant and animal species, personal action is lacking (possibly exemplifying the tension I outline above between recognising an issue but not perceiving any tangible short-term benefits to addressing it). Of particular note is that of those surveyed by Leiserowitz, Maibach, Roser-Renouf, Rosenthal, and Cutler (2017) only 3% reported that their family and friends make ‘a great deal of effort’ and only 8% ‘a lot of effort’ to reduce global warming. A third (31%), however, did indicate that they engaged in ‘a moderate amount of effort’ to reduce global warming, but nearly half (48%) reported making ‘no’ or ‘little effort’.

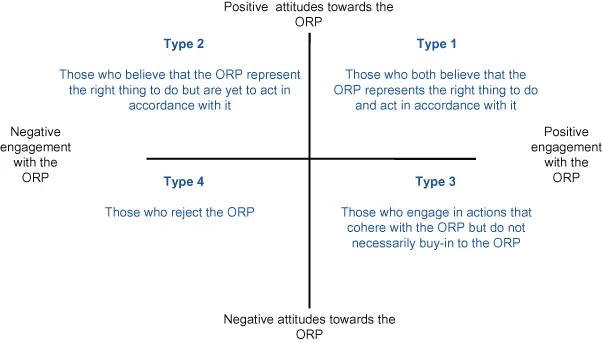

In terms of the ORP relating to human-led climate change, Leiserowitz et al.’s (2017) report shows that we can consider people’s responses to ORPs according to their attitudes towards the ORP and their engagement with the ORP. In other words, (1) whether individuals believe that the ORP is something that reflects how they and others should be behaving and (2) whether they are indeed acting in accordance with the ORP. Assuming that both beliefs/attitudes and actions can be assigned to the dichotomous categories of ‘yes’ or ‘no’, then this specific division of attitudes and actions can be represented by the 2 × 2 matrix set out in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2. Rationality Types.

As a result we can begin to consider individuals as belonging to one of four types as relates to any given ORP. Here ‘Type 1’ individuals are those who believe that the ORP represents the right thing to do and act in accordance with it. In other words, Type 1 individuals are achieving the OR situation of maximising welfare (i.e. welfare for the long-term self or long-term universal). ‘Type 2’ individuals are those who believe that the ORP represents the right thing to do but are yet to act in accordance with it: for instance, they may lack required knowledge, skills or resource to fully engage with the ORP. Type 2 individuals may also require a greater incentive to move away from engaging in more preferential activities such as long haul flights or heavy drinking. ‘Type 3’ individuals do engage in actions that cohere with the ORP but do not necessarily buy-in to the ORP. This may mean, for example, that the fact that their actions cohere with the ORP is simply coincidence or that their actions are driven by other factors (such as budget restraints). Alternatively it may mean that while they previously thought the ORP was a good thing they no longer believe this to be the case. Either way it seems likely that without positive buy-in to the ORP, the coherence of the actions of ‘Type 3’ individuals with the ORP is only likely to be temporary. Finally ‘Type 4’ individuals totally reject the ORP.

Allocating people to the types set out in Figure 1.2 also enables us to determine whether rationality gaps exist: in other words whether outcomes could be more objectively beneficial than they currently are. This is because it is only ‘Type 1’ individuals who maximise well-being. While Types 2–4 are engaging in rational acts this will not be in accordance with what a given ORP suggests is required over the long term. For instance, considering Figure 1.1 people may instead be acting in the interests of the short-term self. And in the case of ‘Type 3’ individuals, their actions are likely to be temporary, and possibly, if disillusioned with the ORP, ‘Type 3s’ may also be supportive of other counter positions. Rationality gaps in essence then represent the proportional differences between those people who might be considered ‘Type 1’ and all others (i.e. those who could potentially be ‘Type 1’).

Of course it’s one thing knowing that people may not always choose the most optimal outcomes, and so exist as one of ‘Types 2–4’ described above, it’s another to understand their decision making in such a way that we can close rationality gaps. As Petrarca (2008) urges it is essential that we ensure not only that people know what is right but that we also help people to do the ‘right things’. In other words there is no point in social scientists simply disseminating knowledge about ORPs: we must also persuade others to act on this knowledge. A similar view is held by Vico (2002) who argues that common sense (i.e. people’s rational choices) must be supported and updated by our increasing understanding of the world. It is clear therefore that as the modern arbiters of virtue or good behaviour4 social scientists must seek to close the optimal rational gaps by devising interventions to help people to change either their behaviours or beliefs, i.e. to help people make better choices. In the next chapter I begin to explore how we might do so.

NOTES