eBook - ePub

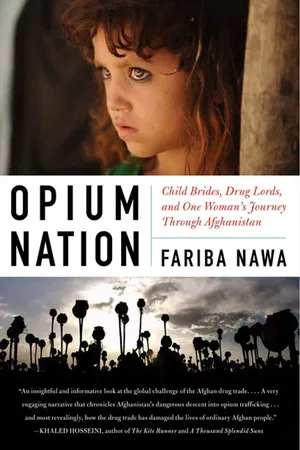

Opium Nation

Child Brides, Drug Lords, and One Woman’s Journey Through Afghanistan

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Afghan-American journalist Fariba Nawa delivers a revealing and deeply personal explorationof Afghanistan and the drug trade which rules the country, from corruptofficials to warlords and child brides and beyond. KhaledHosseini, author of The Kite Runner and AThousand Splendid Suns calls Opium Nation “an insightful andinformative look at the global challenge of Afghan drug trade. Fariba Nawa weaves her personalstory of reconnecting with her homeland after 9/11 with a very engagingnarrative that chronicles Afghanistan’s dangerous descent into opiumtrafficking…and most revealingly, how the drug trade has damaged the lives ofordinary Afghan people.” Readers of Gayle Lemmon Tzemach’sThe Dressmaker of Khair Khanaand Rory Stewart’s The Places Between will find Nawa’spersonal, piercing, journalistic tale to be an indispensable addition to thecultural criticism covering this dire global crisis.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

Home After Eighteen Years

Home After Eighteen Years

Flies buzz and circle my face. I swat them away as I slowly look up to see a dozen men watching me outside the visa building. I’m standing in line at the Iranian border, waiting to cross into my home country, Afghanistan. Men stare at my face and hands. My hair and the rest of my body are covered in a head scarf, slacks, and a long coat, in observance of Iran’s dress requirements for women.

I keep my eyes to the ground to avoid the ogling. An Iranian border agent calls out my name. My hands tremble as I give him my Afghan passport—perhaps the least useful travel document in the world. I’ve hidden my American passport in my bra; Iran restricts visas for American citizens, and the Taliban are wary of Afghan women returning from the United States.

“Where are you coming from?” the agent asks with a serious face.

“Pakistan.”

“What are you doing there?”

“I work for a charity organization.” I actually work for a Pakistani think tank as an English editor, and I’m a freelancer writing articles about Afghan refugees in Pakistan for American media outlets. I don’t share these details with the Iranian border agent, though; they would only raise more questions and delay my journey.

“What were you doing in Iran?”

“Visiting my relatives.”

He eyes me suspiciously and flips through the pages of my passport. Then he stamps the exit visa with “Tybad,” the Iranian border city, and motions me to leave.

It is late morning and a cool fall breeze hits my face. My hands stop shaking but become clammy, my stomach churns with nausea, my head spins. In just a few hours I will be in Herat, my childhood home, for the first time in eighteen years. The anticipation feels a bit like the moment before I delivered my daughter: painful, frightening, yet exhilarating.

I am accompanied by Mobin. The Taliban require that women travel with a male relative, a mahram, but I didn’t have a male relative willing to lead me to war-battered Afghanistan. In Iran, I stayed with Kamran, whose family were our neighbors in Herat. He is the son of Mr. Jawan, a retired opium smuggler, and a close friend of our family. He asked his friend Mobin to act as my mahram. Mobin, a merchant based in Herat, met me at Kamran’s home in Torbat-e-Jam, Iran. He is shy and taciturn; he shows his expressions by raising or lowering his deeply arched dark eyebrows. Mobin imports buttons and lace from Iran to sell in Afghanistan, earning about $3,000 a year. He sees his wife and eighteen-month-old son in Herat one week out of every month. Shrewd and experienced on the road, he promised Kamran he would safely guide me from Iran to Afghanistan and finally back to Pakistan.

Mobin and I walk a few yards from the Iranian side of the border and onto Afghan soil, in the town of Islam Qala. We rent a taxi with two other women; Mobin is acting as their mahram as well. Each woman is dressed in a black chador, a one-piece fabric covering the whole body. The women whisper to each other and wrap one end of their chadors over their mouths. The Taliban have banned music everywhere in the country, but our driver, a tall, unassuming man, slips in a cassette of Farhad Darya, the most renowned Afghan pop singer, and turns up the volume as we head for Herat. He risks the destruction of his tapes and a beating if the Taliban catch him. (The Taliban usually rip out the ribbons from seized video- and audiocassettes and display them in town centers as a lesson to others.) But our driver is among many Afghans who take this risk.

The taxi rolls up and down over sand dunes, lolling me back to the past. The desert we are crossing was the front line in the war when I was a child. I was nine years old the last time I crossed the path of the ancient Silk Road, when my family fled Afghanistan in 1982, during the Soviet invasion. For six hours my parents and older sister walked while I rode on the donkey carrying our belongings until we safely reached Iran, and then Pakistan. We eventually sought asylum in the United States, where I grew up in California. I haven’t stopped dreaming of returning to Afghanistan since I left. I cling to my memories of the nine years I spent there, a mixture of blissful childhood innocence ruptured by the bloodshed of war.

A bump in the road jolts me out of my reminiscences. I take out my journal and write under my black coat. The others in the car see the journal.

“How can you write on such a rough ride?” Mobin asks.

“My handwriting will be bad, but I’ll be able to read it,” I answer.

I scribble as the car jumps, rolling over a big rock. Where are we? Was it here that I cried for water for two hours under the scorching sun? Water had finally arrived, in a plastic oil container from a salty desert well. I drank and gagged, I remember, spitting the water on the donkey I was riding.

I put the journal away and look out the taxi’s dust-covered window. My view is an endless desert dotted with boulders and thorns. The taxi’s tires kick up more dust, and a rain of sand blocks the view for a moment.

Every time a man appears, either walking or in a car in the distance, the other women and I shield our faces with the edge of our head scarves.

“Don’t worry. The Taliban are scared of women,” Mobin says. “They usually stop cars with only men. The ones with women, they just turn their heads.” He’s not kidding. Many of the Taliban were orphans who grew up in Pakistani refugee camps, attending religious schools. Some have had little or no contact with women.

I close my eyes and listen to the voice of Farhad Darya.

In this state of exile

My beloved is not close to me

I’ve lost my homeland

I’ve lost my wit

O dear God

The singer laments his distance from Afghanistan; he recorded this song in Virginia. Darya is loved for his original lyrics, which invoke the nostalgia and painful experience of exile. His songs are steeped in loss, longing, and the warmth the homeland gave him. His music speaks to those inside the country as well as to the Afghan diaspora. I usually become melancholy when I listen to his music, but this time I smile. I’m no longer in exile.

I think I’m getting closer to home.

The war was in its fourth year, and my mother, Sayed Begum; my father, Fazul Haq; and my sister, Faiza, lived in our paternal family property in downtown Herat. My brother, Hadi, had already fled the country. Our home consisted of two rooms and was one of three houses built on two acres of land. The land, once emerald with gardens of herbs and vegetables, was now dry, with only a few surviving pomegranate trees and a blackberry tree. The war, the shortage of water, and the absence of a caretaker—our caretaker, Rasool, died before the war—had led to the land’s neglect. We shared the property with my father’s youngest brother, a dozen of his in-laws, my paternal grandfather, Baba Monshi, and his wife, Bibi Assia.

Baba Monshi’s name was Abdul Karim Ahrary. A renowned essayist and intellectual, he was an adviser on the drafting of Afghanistan’s constitution in 1964 and pioneered the women’s movement in Herat city in the 1960s. He established Donish (Knowledge) Publishers and was the editor of Herat’s official newspaper, Islamic Unison. His protégé was his niece, my aunt Roufa Ahrary, who started Mehri, the first women’s magazine in Herat. Our home was a meeting point for secular intellectuals to debate politics, play chess, and drink tea. Baba Monshi’s opinions were ahead of their time. He believed that women should have the right to an education and he wrote against the injustices of British imperialism and the inequalities in the Afghan government. The government first jailed him in the early twentieth century, then exiled him from Herat to Kabul. His influence had spread in Herat, which made the Afghan monarchy nervous.

By the time I was born, Baba Moshi had lost his once-vibrant capabilities for intellectual thought. When my blood grandmother Bibi Sarah died in 1967, my grandfather married Bibi Assia, who became my step-grandmother. She was a plump and petite woman, and hugging her was like wrapping my arms around a soft pillow. She dedicated her time to caring for my ailing grandfather. In his later years, Baba Monshi spent most of his hours roaming around the property, feeding his gray-and-black cat, Gorba, and giving bread to the ants in the yard. Near the end, he didn’t recognize most of his family, except for his wife, whom he sought out only when he was hungry. Bibi Assia’s biggest gripe was that Baba Monshi would not eat the meat on his plate; instead he fed it to Gorba.

Two miles from our property on Behzad Road was my maternal grandfather’s three-and-a-half-acre orchard home near Herat Stadium, on tree-lined Telecom Road. My mother would take me to Haji Baba’s house every weekend and on holidays. We would stay for several nights at a time. I recall the cheerfulness of my childhood in this home. I’d climb trees, pick fruit, and play with my dozen maternal cousins. The orchard was replete with mulberry, cherry, pomegranate, walnut, apple, peach, and orange trees, as well as grapevines. My grandparents also had a small barn in the back of the land, with a few cows. A narrow creek cut through the trees, and their eight-room redbrick house sat in the center of the land. The rooms were full of people. Haji Baba’s real name was Sayed Akbar Hossaini and he was a financial adviser for the government who traveled to other districts and provinces for work. He also wrote essays, which one of my maternal uncles, Dr. Said Maroof Ramia, compiled into a book, published in Germany in 2006, titled The Authorities of Herat. Haji Baba did not get to spend much time with his family, but Bibi Gul, my maternal step-grandmother, was hardly alone with ten children—my aunts and uncles—and a dozen grandchildren. Fewer bombs dropped near Haji Baba’s property than ours, because it was secure with the presence of the nearby police station and several government offices. The orchard there was my sanctuary.

Outside the gated properties was a lively city with horse wagons, public buses, shoppers, and a five-thousand-year history shared by the city where we lived. The city was surrounded by four-meter-high walls that hid the houses, most constructed from adobe or concrete. Five gates served as entrances and exits for the city. Herat’s older homes, including the remains of the Jewish neighborhood, were two-story structures decorated with intricate tilework and carvings, and were designed with square courtyards and fountains. Among the houses and shops were numerous architectural wonders that made the city an outdoor museum of Afghanistan, including a centuries-old fort, spectacular minarets, shrines, and mosques.

Herat’s history is wrought with peaks and valleys of war and conquest, of progress and destruction. Various eras have labeled Herat the cradle of art and culture and the pearl of the region. Prominent Sufi poets Khwaja Abdullah Ansari and Nuruddin Jami and medieval miniaturist Behzad all flourished in Herat. Two periods define extreme eras for the city: In the thirteenth century, Genghis Khan held the city under siege after his son was murdered by native rebels. The Mongol leader killed thousands, leaving only forty people alive. Nearly two centuries later, during the Turkic Timurid dynasty, Herat served as the capital of the Turkic Mongol empire and thrived with advancements in art and education. Under the leadership of Queen Gowhar Shad—who ruled for ten years but whose influence spanned generations—magnificent architecture was built that still stands today. The Muslim queen of Sheba, as Gowhar Shad is widely known, also focused her attention on scholarship and diplomacy.

This glorious past was forgotten when bombs rained on the city during the Soviet invasion and wealthy, educated residents began to flee in the thousands. The American-funded mujahideen rebels fought ferocious battles against a ruling Communist government aided by Soviet troops and airpower. The battles occurred a mile from our Behzad Road home, in neighborhoods such as Baraman, Houza Karbas, and Shahzadaha. Of the seven mujahideen factions, Jamiat-e-Islami fought in Herat under the leadership of Ismail Khan, an educated soldier and warrior. Khan was ally to the head of Jamiat, Ahmad Shah Massoud, who became famous in the United States after the Taliban employed two Arab suicide bombers to kill him two days before September 11. The United States gave weapons to the Pakistani intelligence agency, ISI, to hand over to the mujahideen, who numbered roughly 200,000. The mujahideen had guns, rockets, and Stinger missiles, but also knowledge of the terrain and, most important, local support. The Afghan Communist government had a shrinking army—Afghan soldiers deserted or defected to the mujahideen—but was reinforced by about 120,000 Soviet troops and Soviet helicopters, planes, tanks, missiles, and mines. The rebels attacked from behind hills, shrines, and even some houses; the Soviets sometimes carpet-bombed in response.

A normal day at our home included the rumble of gunshots and rockets. We ignored the sounds and carried on with life. My sister played volleyball with relatives, I played hopscotch, and my father took his daily walks around the property after coming home from his job as an administrative director at the National Fertilizer Company, an American-funded, Afghan government−owned project that offered chemical fertilizer to farmers. On some days, however, the shots and explosions barely missed members of my family.

One spring day, when I was eight years old, Bibi Assia was extracting rosewater from the pink roses that bloomed on our property when a stray bullet passed just above her four-foot-nine inches of height. (It was hard to place the origin of the bullets because there were always so many of them.) The bullet struck the brick wall of our house and burned a hole in it. After the incident, Bibi Assia hid in a room for a month, coming out only when necessary. And our family developed a morbid sense of humor.

“Assia Jan’s height saved her life. Who said being short is a bad thing?” my father joked. That winter, he nearly met his own bullet. One day my mother (Madar), my sister, and I were playing cards around the korsi—a table warmed by a makeshift heater, with a charcoal barbecue lit up underneath it—with a big blanket covering our bodies, when a bullet fractured the window of our living room. The golden bullet rushed over our heads, ricocheted off a wall, and fell to the floor, just missing my father’s hand—he had been pacing the room, as he often did out of habit. We all thought the Communist government soldiers or the mujahideen were raiding our house, but when my father ventured outside to investigate, he found there had been only the lone bullet.

One attack that still disturbs my dreams occurred at my school, Lycée Mehri, a year later, in July 1982, when I was nine years old. In provinces with heavy snowfall, such as Herat, schools are open in the summer and closed for the winter. Girls from kindergarten up through the twelfth grade attended my school, which was on an unpaved block about two football fields from our home. The day of the attack, Madar let me play hooky, and she and I went to take our weekly bath at the public bathhouse, a few miles from our neighborhood, while Faiza, who was in the tenth grade, went to school.

The bathhouse was a place to strip down, relax, and gossip, though the talk often turned to the war. One of the women there that day, with gold bangles and stringy hair, told my mom that her husband had heard that the mujahideen planned to attack Lycée Mehri because girls were being taught Communist propaganda there. “Haven’t you noticed how there are fewer cars and horse wagons on the road?” the woman said. “People are staying home because they are afraid of a big attack right here in town.”

These rumors were too common to take seriously. Madar shrugged off the news and asked the woman why she had come out if she was so worried about an attack. Later, when we left the warmth of the bathhouse, a cool summer wind hit our faces and we noticed that the streets were empty and the shops that were usually bustling with customers were closed. We walked halfway home because we couldn’t find a taxi, wagon, or bus any sooner, and then we finally hailed a horse wagon.

Madar seemed worried when we reached our house. “I hope that woman at the bathhouse was wrong about the school being attacked.” I remained quiet and set about ironing my favorite fuchsia chiffon dress, which my mom had made for me. I brushed off my mother’s concern and wondered what I was missing at school.

Just then, there was a boom, a much bigger and closer on...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Prologue

- Chapter One - Home After Eighteen Years

- Chapter Two - Four Decades of Unrest

- Chapter Three - A Struggle for Coherency

- Chapter Four - My Father’s Voyage

- Chapter Five - Meeting Darya

- Chapter Six - A Smuggling Tradition

- Chapter Seven - The Opium Bride

- Chapter Eight - Traveling on the Border of Death

- Chapter Nine - Where the Poppies Bloom

- Chapter Ten - The Smiles of Badakhshan

- Chapter Eleven - My Mother’s Kabul

- Chapter Twelve - Women on Both Sides of the Law

- Chapter Thirteen - Adventures in Karte Parwan

- Chapter Fourteen - Raids in Takhar

- Chapter Fifteen - Uprisings Against Warlords

- Chapter Sixteen - The Good Agents

- Chapter Seventeen - In Search of Darya

- Chapter Eighteen - Through the Mesh

- Chapter Nineteen - Letting Go

- Epilogue - 2010

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Acknowledgments

- Photo Section

- About the Author

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Opium Nation by Fariba Nawa in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.