A Day at the Supermarket

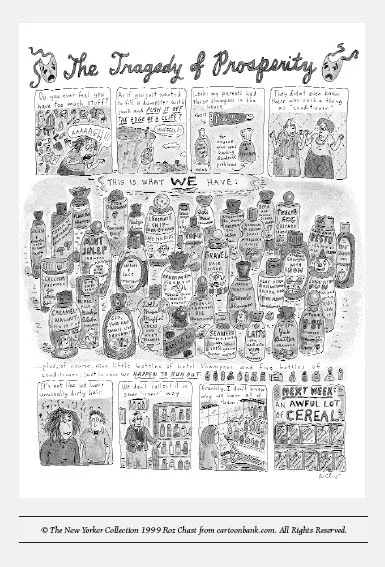

SCANNING THE SHELVES OF MY LOCAL SUPERMARKET RECENTLY, I found 85 different varieties and brands of crackers. As I read the packages, I discovered that some brands had sodium, others didn’t. Some were fat-free, others weren’t. They came in big boxes and small ones. They came in normal size and bite size. There were mundane saltines and exotic and expensive imports.

My neighborhood supermarket is not a particularly large store, and yet next to the crackers were 285 varieties of cookies. Among chocolate chip cookies, there were 21 options. Among Goldfish (I don’t know whether to count them as cookies or crackers), there were 20 different varieties to choose from.

Across the aisle were juices—13 “sports drinks,” 65 “box drinks” for kids, 85 other flavors and brands of juices, and 75 iced teas and adult drinks. I could get these tea drinks sweetened (sugar or artificial sweetener), lemoned, and flavored.

Next, in the snack aisle, there were 95 options in all—chips (taco and potato, ridged and flat, flavored and unflavored, salted and unsalted, high fat, low fat, no fat), pretzels, and the like, including a dozen varieties of Pringles. Nearby was seltzer, no doubt to wash down the snacks. Bottled water was displayed in at least 15 flavors.

In the pharmaceutical aisles, I found 61 varieties of suntan oil and sunblock, and 80 different pain relievers—aspirin, acetaminophen, ibuprofen; 350 milligrams or 500 milligrams; caplets, capsules, and tablets; coated or uncoated. There were 40 options for toothpaste, 150 lipsticks, 75 eyeliners, and 90 colors of nail polish from one brand alone. There were 116 kinds of skin cream, and 360 types of shampoo, conditioner, gel, and mousse. Next to them were 90 different cold remedies and decongestants. Finally, there was dental floss: waxed and unwaxed, flavored and unflavored, offered in a variety of thicknesses.

Returning to the food shelves, I could choose from among 230 soup offerings, including 29 different chicken soups. There were 16 varieties of instant mashed potatoes, 75 different instant gravies, 120 different pasta sauces. Among the 175 different salad dressings were 16 “Italian” dressings, and if none of them suited me, I could choose from 15 extra-virgin olive oils and 42 vinegars and make my own. There were 275 varieties of cereal, including 24 oatmeal options and 7 “Cheerios” options. Across the aisle were 64 different kinds of barbecue sauce and 175 types of tea bags.

Heading down the homestretch, I encountered 22 types of frozen waffles. And just before the checkout (paper or plastic; cash or credit or debit), there was a salad bar that offered 55 different items.

This brief tour of one modest store barely suggests the bounty that lies before today’s middle-class consumer. I left out the fresh fruits and vegetables (organic, semi-organic, and regular old fertilized and pesticized), the fresh meats, fish, and poultry (free-range organic chicken or penned-up chicken, skin on or off, whole or in pieces, seasoned or unseasoned, stuffed or empty), the frozen foods, the paper goods, the cleaning products, and on and on and on.

A typical supermarket carries more than 30,000 items. That’s a lot to choose from. And more than 20,000 new products hit the shelves every year, almost all of them doomed to failure.

Comparison shopping to get the best price adds still another dimension to the array of choices, so that if you were a truly careful shopper, you could spend the better part of a day just to select a box of crackers, as you worried about price, flavor, freshness, fat, sodium, and calories. But who has the time to do this? Perhaps that’s the reason consumers tend to return to the products they usually buy, not even noticing 75% of the items competing for their attention and their dollars. Who but a professor doing research would even stop to consider that there are almost 300 different cookie options to choose among?

Supermarkets are unusual as repositories for what are called “nondurable goods,” goods that are quickly used and replenished. So buying the wrong brand of cookies doesn’t have significant emotional or financial consequences. But in most other settings, people are out to buy things that cost more money, and that are meant to last. And here, as the number of options increases, the psychological stakes rise accordingly.

Shopping for Gadgets

CONTINUING MY MISSION TO EXPLORE OUR RANGE OF CHOICES, I left the supermarket and stepped into my local consumer electronics store. Here I discovered:

- 45 different car stereo systems, with 50 different speaker sets to go with them.

- 42 different computers, most of which could be customized in various ways.

- 27 different printers to go with the computers.

- 110 different televisions, offering high definition, flat screen, varying screen sizes and features, and various levels of sound quality.

- 30 different VCRs and 50 different DVD players.

- 20 video cameras.

- 85 different telephones, not counting the cellular phones.

- 74 different stereo tuners, 55 CD players, 32 tape players, and 50 sets of speakers. (Given that these components could be mixed and matched in every possible way, that provided the opportunity to create 6,512,000 different stereo systems.) And if you didn’t have the budget or the stomach for configuring your own stereo system, there were 63 small, integrated systems to choose from.

Unlike supermarket products, those in the electronics store don’t get used up so fast. If we make a mistake, we either have to live with it or return it and go through the difficult choice process all over again. Also, we really can’t rely on habit to simplify our decision, because we don’t buy stereo systems every couple of weeks and because technology changes so rapidly that chances are our last model won’t exist when we go out to replace it. At these prices, choices begin to have serious consequences.

Shopping by Mail

MY WIFE AND I RECEIVE ABOUT 20 CATALOGS A WEEK IN THE MAIL. We get catalogs for clothes, luggage, housewares, furniture, kitchen appliances, gourmet food, athletic gear, computer equipment, linens, bathroom furnishings, and unusual gifts, plus a few that are hard to classify. These catalogs spread like a virus—once you’re on the mailing list for one, dozens of others seem to follow. Buy one thing from a catalog and your name starts to spread from one mailing list to another. From one month alone, I have 25 clothing catalogs sitting on my desk. Opening just one of them, a summer catalog for women, we find

- 19 different styles of women’s T-shirts, each available in 8 different colors,

- 10 different styles of shorts, each available in 8 colors,

- 8 different styles of chinos, available in 6 to 8 colors,

- 7 different styles of jeans, each available in 5 colors,

- dozens of different styles of blouses and pants, each available in multiple colors,

- 9 different styles of thongs, each available in 5 or 6 colors.

And then there are bathing suits—15 one-piece suits, and among two-piece suits:

- 7 different styles of tops, each in about 5 colors, combined with,

- 5 different styles of bottoms, each in about 5 colors (to give women a total of 875 different “make your own two-piece” possibilities).

Shopping for Knowledge

THESE DAYS, A TYPICAL COLLEGE CATALOG HAS MORE IN COMMON with the one from J. Crew than you might think. Most liberal arts colleges and universities now embody a view that celebrates freedom of choice above all else, and the modern university is a kind of intellectual shopping mall.

A century ago, a college curriculum entailed a largely fixed course of study, with a principal goal of educating people in their ethical and civic traditions. Education was not just about learning a discipline—it was a way of raising citizens with common values and aspirations. Often the capstone of a college education was a course taught by the college president, a course that integrated the various fields of knowledge to which the students had been exposed. But more important, this course was intended to teach students how to use their college education to live a good and an ethical life, both as individuals and as members of society.

This is no longer the case. Now there is no fixed curriculum, and no single course is required of all students. There is no attempt to teach people how they should live, for who is to say what a good life is? When I went to college, thirty-five years ago, there were almost two years’ worth of general education requirements that all students had to complete. We had some choices among courses that met those requirements, but they were rather narrow. Almost every department had a single, freshman-level introductory course that prepared the student for more advanced work in the department. You could be fairly certain, if you ran into a fellow student you didn’t know, that the two of you would have at least a year’s worth of courses in common to discuss.

Today, the modern institution of higher learning offers a wide array of different “goods” and allows, even encourages, students—the “customers”—to shop around until they find what they like. Individual customers are free to “purchase” whatever bundles of knowledge they want, and the university provides whatever its customers demand. In some rather prestigious institutions, this shopping-mall view has been carried to an extreme. In the first few weeks of classes, students sample the merchandise. They go to a class, stay ten minutes to see what the professor is like, then walk out, often in the middle of the professor’s sentence, to try another class. Students come and go in and out of classes just as browsers go in and out of stores in a mall. “You’ve got ten minutes,” the students seem to be saying, “to show me what you’ve got. So give it your best shot.”

About twenty years ago, somewhat dismayed that their students no longer shared enough common intellectual experiences, the Harvard faculty revised its general education requirements to form a “core curriculum.” Students now take at least one course in each of seven different broad areas of inquiry. Among those areas, there are a total of about 220 courses from which to choose. “Foreign Cultures” has 32, “Historical Study” has 44, “Literature and the Arts” has 58, “Moral Reasoning” has 15, as does “Social Analysis,” Quantitative Reasoning” has 25, and “Science” has 44. What are the odds that two random students who bump into each other will have courses in common?

At the advanced end of the curriculum, Harvard offers about 40 majors. For students with interdisciplinary interests, these can be combined into an almost endless array of joint majors. And if that doesn’t do the trick, students can create their own degree plan.

And Harvard is not unusual. Princeton offers its students a choice of 350 courses from which to satisfy its general education requirements. Stanford, which has a larger student body, offers even more. Even at my small school, Swarthmore College, with only 1,350 students, we offer about 120 courses to meet our version of the general education requirement, from which students must select nine. And though I have mentioned only extremely selective, private institutions, don’t think that the range of choices they offer is peculiar to them. Thus, at Penn State, for example, liberal arts students can choose from over 40 majors and from hundreds of courses intended to meet general education requirements.

There are many benefits to these expanded educational opportunities. The traditional values and traditional bodies of knowledge transmitted from teachers to students in the past were constraining and often myopic. Until very recently, important ideas reflecting the values, insights, and challenges of people from different traditions and cultures had been systematically excluded from the curriculum. The tastes and interests of the idiosyncratic students had been stifled and frustrated. In the modern university, each individual student is free to pursue almost any interest, without having to be harnessed to what his intellectual ancestors thought was worth knowing. But this freedom may come at a price. Now students are required to make choices about education that may affect them for the rest of their lives. And they are forced to make these choices at a point in their intellectual development when they may lack the resources to make them intelligently.

Shopping for Entertainment

BEFORE THE ADVENT OF CABLE, AMERICAN TELEVISION VIEWERS HAD the three networks from which to choose. In large cities, there were up to a half dozen additional local stations. When cable first came on the scene, its primary function was to provide better reception. Then new stations appeared, slowly at first, but more rapidly as time went on. Now there are 200 or more (my cable provider offers 270), not counting the on-demand movies we can obtain with just a phone call. If 200 options aren’t enough, there are special subscription services that allow you to watch any football game being played by a major college anywhere in the country. And who knows what the cutting-edge technology will bring us tomorrow.

But what if, with all these choices, we find ourselves in the bind of wanting to watch two shows broadcast in the same time slot? Thanks to VCRs, that’s no longer a problem. Watch one, and tape one for later. Or, for the real enthusiasts among us, there are “picture-in-picture” TVs that allow us to watch two shows at the same time.

And all of this is nothing compared to the major revolution in TV watching that is now at our doorstep. Those programmable, electronic boxes like TiVo enable us, in effect, to create our own TV stations. We can program those devices to find exactly the kinds of shows we want and to cut out the commercials, the promos, the lead-ins, and whatever else we find annoying. And the boxes can “learn” what we like and then “suggest” to us programs that we may not have thought of. We can now watch whatever we want whenever we want to. We don’t have to schedule our TV time. We don’t have to look at the TV page in the newspaper. Middle of the night or early in the morning—no matter when that old movie is on, it’s available to us exactly when we want it.

So the TV experience is now the very essence of choice without boundaries. In a decade or so, when these boxes are in everybody’s home, it’s a good bet that when folks gather around the watercooler to discuss last night’s big TV events, no two of them will have watched the same shows. Like the college freshmen struggling in vain to find a shared intellectual experience, American TV viewers will be struggling to find a shared TV experience.

But Is Expanded Choice Good or Bad?

AMERICANS SPEND MORE TIME SHOPPING THAN THE MEMBERS OF any other society. Americans go to shopping centers about once a week, more often than they go to houses of worship, and Americans now have more shopping centers than high schools. In a recent survey, 93 percent of teenage girls surveyed said that shopping was their favorite activity. Mature women also say they like shopping, but working women say that shopping is a hassle, as do most men. When asked to rank the pleasure they get from various activities, grocery shopping ranks next to last, and other shopping fifth from the bottom. And the trend over recent years is downward. Apparently, people are shopping more now but enjoying it less.

There is something puzzling about these findings. It’s not so odd, perhaps, that people spend more time shopping than they used to. With all the options available, picking what you want takes more effort. But why do people enjoy it less? And if they do enjoy it less, why do they keep doing it? ...