eBook - ePub

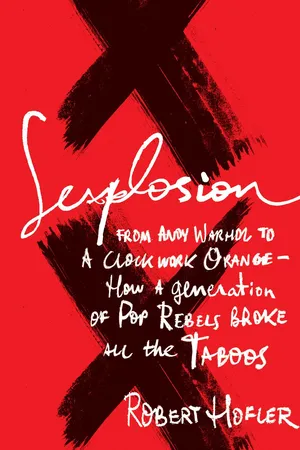

Sexplosion

From Andy Warhol to A Clockwork Orange-- How a Generation of Pop Rebels Broke All the Taboos

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sexplosion

From Andy Warhol to A Clockwork Orange-- How a Generation of Pop Rebels Broke All the Taboos

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Winter 1968, Guts

For purveyors of the moral status quo, the first four weeks of 1968 emerged as an unqualified disaster.

In January alone, Off-Broadway performances began for Mart Crowley’s play The Boys in the Band, about an expletive-laden, gay birthday party gone bad. Terry Southern fulfilled his fantasy, and then his nightmare, of seeing his long-banned Candy finally go before the movie cameras. Jane Fonda, still filming Barbarella in Rome, fretted over the film’s outer-space striptease, which director-husband-svengali Roger Vadim had promised to fix in postproduction by hiding her privates with the film’s opening credits. Kenneth Tynan went from theater critic to theater impresario, asking everyone from Samuel Beckett to Jules Feiffer to contribute skits for his new erotic stage revue, Oh! Calcutta! Director Lindsay Anderson began filming If . . . , set in an English boys’ school rife with anarchy, homosexual love, and a heterosexual wrestling match. United Artists green-lit John Schlesinger’s exploration of the Forty-Second Street hustler scene, Midnight Cowboy. Director Tom O’Horgan toyed with adding a nude scene to his upcoming Broadway incarnation of the new musical Hair. Little, Brown published Gore Vidal’s novel about a transsexual, Myra Breckinridge, while over at Knopf, Inc., they began printing the first seventy thousand copies of John Updike’s tome on suburban spouse-swapping, Couples. And Lance Loud, only a few years away from being TV’s first gay star, was so inspired by seeing Warhol’s Chelsea Girls that he promptly dyed his hair silver to match his idol’s wig.

In 1968, the world did not yet know of the teenager from Santa Barbara, but Lance Loud was already well on his way to being the Zelig of the Sexplosion years as he filtered and absorbed the rapid changes in pop culture, not to make art but to turn his life into art. All he needed was a little help from some documentary filmmakers, the yet-to-be-launched Public Broadcasting Service, and, of course, Andy Warhol himself.

That January, Warhol continued to challenge the sexual status quo, but not from his Factory. He left Manhattan to visit Oracle, Arizona, where he was making a new film, a Western, which was of such concern to the men of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI that they decided to open a file on him. Almost overnight, Chelsea Girls (the title lost its original “the” on its way up from the underground) had turned Warhol into a target, the bureau’s need to rout out revolutionaries no longer limited to just communists.

Warhol’s go-to movie-guy Paul Morrissey doubted that he could ever top those Chelsea Girls reviews in Newsweek (“fleshpots of Caligula’s Rome!”) and Time (“a sewer!”) with this new, as yet untitled movie. And there were other challenges. If three thousand dollars and a four-day shooting schedule were good enough for Chelsea Girls, Warhol thought it would be good enough for the half dozen or so subsequent films that Morrissey was to make, including this new Western that updated Shakespeare’s tale of two star-crossed lovers. “I had this idea of doing Romeo and Juliet with groups of cowboys and cowgirls,” Morrissey explained. “But no girls came because they had a quarrel with Viva.”

Viva, aka Janet Susan Mary Hoffmann, took her name from Viva paper towels. And there were other reasons she morphed into the number-one superstar in the Factory firmament after Warhol fashion icon Edie Sedgwick demanded and got herself removed from Chelsea Girls. In addition to her Garbo-esque beauty, which included none of the great Swede’s discretion or fear of exposure, Viva knew how to get attention in a room, if not a movie, full of flamboyant male homosexuals. As she explained it in her lazy soprano whine, “Take off your clothes!”

She was also one of the first Warhol actors to be called a superstar. “They felt they were doing something special with those movies,” said Joe Dallesandro, who started at the Factory as a doorman and later graduated to appearing before Warhol’s camera, usually stark naked to the delight of everyone except himself. “How can you be doing something special in three or four days?” he asked.

Since a Western, even an Andy Warhol Western, couldn’t be shot in New York City, the movie Morrissey envisioned, about a cowboy Romeo and his cowgirl Juliet, needed the appropriate locale. Morrissey chose Oracle, Arizona, where a few John Wayne pictures had been shot. The citizens of Oracle liked the Duke. They didn’t like Warhol or Morrissey. After all, in what other Western did a woman ride into town with her nurse—her male nurse!—and end up being raped by a few bored cowboys who’d much prefer bedding a handsome male drifter?

Viva put it more succinctly. “The story is I run a whorehouse outside of town,” she said.

Warhol wanted to call it Fuck, then he considered The Glory of the Fuck, but ultimately settled on the more atmospheric, less graphic Lonesome Cowboys.

On the first day of shooting in Oracle, Viva showed up in a very proper English riding habit, complete with a stock and black leather boots. She’d picked the outfit herself, explaining, “I just woke up from a bad LSD trip and I think I’m in Virginia with Jackie Kennedy.” As it turned out, she needed the stock, being the only woman in the company, which turned out not to be quite as one hundred percent gay as she had hoped. “We were staying together at this guest ranch and it just went on all night. Every night I’d change rooms and every night they’d all be in there with me,” she complained to Andy Warhol.

It concerned Andy, especially what was happening off-camera between his leading lady and the film’s cowboy Romeo, an actor named Tom Hompertz. “Stay away from Tom, save it for the movie!” he kept telling Viva.

Viva claimed she was being attacked by other men on the set. “I was just raped again,” she told Andy on morning two of what was only a four-day shoot.

As with every scene in a Paul Morrissey–directed movie, the actors made it up as they went along. Like the scene where five of them rush Viva as she gets off her horse and everybody screams, “Fuck her! Fuck her!” and proceed to tear off her clothes and then mount her.

It was this scene that compelled one resident of Oracle to lodge a complaint with the FBI, which promptly sent an agent or two out west. “There were planes overhead,” Joe Dallesandro said of the shoot. “That was pretty funny.”

The FBI opened a file on Andy Warhol, created under the category “ITOM: Interstate Transportation of Obscene Matter,” and in his report an agent didn’t stint on the details. As he recorded it, “All of the males in the cast displayed homosexual tendencies and conducted themselves toward one another in an effeminate manner. . . .

“One of the cowboys practiced his ballet and a conversation ensued regarding the misuse of mascara by one of the other cowboys. . . .

“There was no plot to the film and no development of character throughout. It was rather a remotely-connected series of scenes which depicted situations of sexual relationships of homosexual and heterosexual nature.”

Luckily for Warhol and company, Lonesome Cowboys had long wrapped by the time the FBI report made its way back to Washington, D.C.

IF THE FBI CAME lately to the work of Andy Warhol, J. Edgar Hoover’s men had already opened and closed its file on Terry Southern when his novel Candy (written ten years earlier with limited input from the drug-addled Mason Hoffenberg) went into production as a movie that January at the Incom Studios in Rome.

The bureau had opened its Southern investigation in February 1965. Only the year before, G. P. Putnam’s had made Southern’s “dirty book,” about an adventurously promiscuous American girl, legally available in the United States, where it quickly rose to the top of the bestseller lists despite having already sold over twelve million contraband copies under both its original title and Lollipop. The novel got a boost stateside when Publishers Weekly labeled it “sick sex.”

After Candy’s initial publication in France, Southern had gone on to write the screenplay for Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove and been nominated for an Oscar. The FBI, however, didn’t care about awards not won. Its file labeled him a “pornographer,” and Candy, in the bureau’s estimation, was the least of it:

“With reference to [Southern’s] pornographic library of films . . . it is not known to this office whether it is a local violation in Connecticut to display films to ‘guests’ and it is therefore left to the discretion of the bureau as to whether such information should be made available, strictly on a confidential basis, to a local law enforcement agency covering Southern’s place of residence.”

Regarding the novel Candy, the FBI’s internal review found it “not a suitable vehicle for prosecution.” As the file concluded, “ ‘Candy,’ for all its sexual descriptions and foul language, is primarily a satirical parody of the pornographic books which currently flood our newsstands. Whatever erotic impact or prurient appeal it has is thoroughly diluted by the utter absurdity and improbability of the situations described.”

The makers of the Candy movie weren’t quite as liberal as the FBI. They flat out rejected Southern’s script for its sin of inclusion regarding the book’s infamous hunchback character, who performs an unusual sex act at the heroine’s insistence. As it was described in the novel, “The hunchback hesitated, and then lunged headlong toward her, burying his hump between Candy’s legs as she hunched wildly, pulling open her little labias in an absurd effort to get it in her. ‘Your hump! Your hump!’ she kept crying, scratching and clawing at it now.”

In fact, the hunchback pages of Candy (“Give me your hump!”) were second only to the novel’s closing incest scene (“Good Grief—It’s Daddy!”) as required late-night reading at better frat houses everywhere.

Southern just couldn’t bear to lose the hunchback in the movie version. “These scenes were very dear to Terry’s heart because it was the first he wrote for the book,” noted his longtime partner, Gail Gerber. “Holding firm and refusing to delete them from the screenplay, he was fired and lost control over his property.”

The Texas-born Southern, who had been described as having all the charm of a walking hangover, put the controversy a bit more delicately. “I have nothing to do with it,” he said of the movie, “having withdrawn when they insisted on taking out the hunchback.”

Worse than their deleting the hunchback was their hiring director Christian Marquand, who’d never directed a movie before and whose major qualification for the job had something to do with his helping good friend Marlon Brando buy the French Polynesian atoll of Tetiaroa. Brando was nothing if not loyal, and through his efforts Marquand not only landed the Candy gig but was able to hire, at fifty thousand dollars a week per star, other high-profile actors, including Walter Matthau, James Coburn, Ringo Starr, and Richard Burton, who never quite forgave Brando the indignity that was to be Candy, the movie.

“We were all kind of gathered around the idea of doing a 1960s movie,” said Coburn, who played Dr. Krankheit. “Our attitude was ‘Let’s see if we can do it.’ Nudity was beginning to come in, fucking on-screen, and it was all much freer.”

Buck Henry wrote the screenplay—or, more aptly, was in the process of writing it as the production progressed. Southern kept calling him that “sit-com writer,” referring to Henry’s Get Smart days, unaware that Henry had also recently enjoyed a fair degree of success with his screenplay for The Graduate.

Henry returned the insult by saying that the direction of his screenplay would be “every one conceivable away from the book.”

When Coburn’s week of work on the film approached that January, he flew to Rome, only to be met at the airport by the film’s novice director. “Well, there’s been a little problem,” Marquand informed him. “We’ll probably have to close down for a week, or at least until we can do some shooting that Ewa isn’t in.”

Ewa was Ewa Aulin, an unknown Scandinavian actress who’d been cast as the all-American girl Candy. Her accent didn’t matter, Marquand insisted. She would be dubbed.

As Coburn and Marquand spoke on the tarmac, Ewa Aulin was no longer in Rome, having undergone what was politely being called a “rest cure,” which had something to with her being put “to sleep out in a little resort town on the coast, Taormina.”

Aulin had trouble playing her scenes opposite Marlon Brando, cast as the Great Guru Grindl, who, outfitted in Indian robes and long black wig, seduces Candy in a big semi-truck that doubles as his meditation room as he roams America. Brando couldn’t stop wanting to have sex with Aulin, and Aulin couldn’t stop laughing at Brando.

“She had a wonderful ass, man, and Marlon just couldn’t resist,” said Coburn. “He’d started coming on to her pretty strong, turning on his great charm, even during their scenes together. . . . She would look at him in this fright wig, and just get hysterical. He was so funny and ingratiating to begin with—only now he wanted to fuck her, so that was the icing on the cake. It was overwhelming. She just went over the edge.”

Stuck away in a hotel in Taormina, Aulin was given injections to keep her sedated until she ceased giggling. “Soon, rumors reached Hollywood that the decadent production had kept Aulin high just for the fun of it,” reported Southern’s son, Nile.

No one knew how the movie—or, for that matter, the production—would end. “We’re keeping it a secret,” said Buck Henry.

Brando described the ensuing chaos more graphically. “This movie makes as much sense as a rat fucking a grapefruit,” he said.

IT WAS NOT GORE VIDAL’S intention to top Terry Southern or Andy Warhol, who was less than a year away from bringing transsex...

Table of contents

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: 1966 and 1967, Caution

- 1 - Winter 1968, Guts

- 2 - Spring 1968, Partners

- 3 - Summer 1968, Politics

- 4 - Autumn 1968, Revelry

- 5 - Winter 1969, Bonanza

- 6 - Spring 1969, Fetishes

- 7 - Summer 1969, Revolution

- 8 - Autumn 1969, Trauma

- 9 - Winter 1970, Outrage

- 10 - Spring 1970, Kisses

- 11 - Summer 1970, Retreat

- 12 - Autumn 1970, Arrests

- 13 - 1971, Fatigue

- 14 - 1972, Frenzy

- 15 - Winter 1973, Backlash

- Epilogue: Spring 1973 and Beyond, Finales

- Photographic Section

- Acknowledgments

- Bibliography

- Notes

- Index

- About the Author

- Also by Robert Hofler

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Sexplosion by Robert Hofler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & History of Architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.