![]()

Chapter One

“I Had This Strange Dream Again Last Night”

JOHN WILKES BOOTH AWOKE GOOD FRIDAY MORNING, APRIL 14, 1865, hungover and depressed. The Confederacy was dead. His cause was lost and his dreams of glory over. He did not know that this day, after enduring more than a week of bad news and bitter disappointments, he would enjoy a stunning reversal of fortune. No, all he knew this morning when he crawled out of bed in room 228 at the National Hotel, one of Washington’s finest and naturally his favorite, was that he could not stand another day of Union victory celebrations.

Booth assumed that April 14 would unfold as the latest in a blur of eleven bad days that began on April 3 when Richmond, the Confederacy’s citadel, fell to the Union. The very next day the tyrant, Abraham Lincoln, visited his captive prize and had the audacity to sit behind the desk occupied by the first and last president of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis. Then, on April 9, at Appomattox Court House, Robert E. Lee and his glorious Army of Northern Virginia surrendered. Two days later Lincoln made a speech proposing to give blacks the right to vote, and last night, April 13, all of Washington celebrated with a grand illumination of the city. And today, in Charleston harbor, the Union planned to stage a gala celebration to mark the retaking of Fort Sumter, where the war began four years ago. These past eleven days had been the worst of Booth’s young life.

He was the son of the legendary actor and tragedian Junius Brutus Booth, and brother to Edwin Booth, one of the finest actors of his generation. Twenty-six years old, impossibly vain, preening, emotionally flamboyant, possessed of raw talent and splendid élan, and a star member of this celebrated theatrical family—the Barrymores of their day—John Wilkes Booth’s day began in the dining room of the National, where he was seen eating breakfast with Miss Carrie Bean. Nothing unusual about that—Booth, a voluptuous connoisseur of young women, never had trouble finding female company. Around noon he walked over to Ford’s Theatre on Tenth Street between E and F, a block above Pennsylvania Avenue, to pick up his mail. Accepting correspondence on behalf of itinerant actors was a customary privilege Ford’s offered to friends of the house. Earlier that morning Henry Clay Ford, one of the three brothers who ran the theatre, ate breakfast and then walked to the big marble post office at Seventh and F and picked up the mail. There was a letter for Booth.

That morning another letter arrived at the theatre. There had been no time to mail it, so its sender, Mary Lincoln, used the president’s messenger to bypass the post office and hand-deliver it. The Fords did not even have to read the note to know the good news it contained. The mere arrival of the White House messenger told them that the president was coming tonight! It was a coup against their chief rival, Grover’s Theatre, which was offering a more exciting entertainment: Aladdin! Or His Wonderful Lamp. Master Tad Lincoln and chaperone would represent the family there. The letter, once opened, announced even greater news. Yes, the president and Mrs. Lincoln would attend this evening’s performance of Tom Taylor’s popular if tired comedy Our American Cousin. But the big news was that General Ulysses S. Grant was coming with them. The Lincolns’ timing delighted the Fords. Good Friday was traditionally a slow night, and news that not only the president—after four years a familiar sight to Washingtonians—but also General Grant, a rare visitor to town and fresh from his victory at Appomattox, would attend, was sure to spur ticket sales. This would please Laura Keene, who was making her one thousandth performance in the play; tonight’s show was a customary “benefit,” awarding her a rich share of the proceeds. The Lincolns had given the Fords the courtesy of notification early enough in the day for the brothers to promote their appearance and to decorate and join together the two boxes—seven and eight—that, by removal of a simple partition, formed the president’s box.

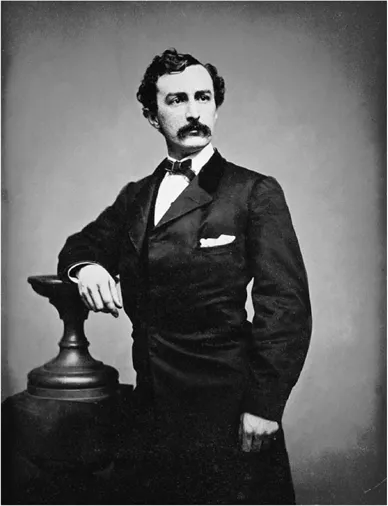

“The most beautiful black eyes in the world.”

John Wilkes Booth at the height of his fame.

By the time Booth arrived at Ford’s, the president’s messenger had come and gone. Sometime between noon and 12:30 P.M. as he sat outside on the top step in front of the main entrance to Ford’s reading his letter, Booth heard the galvanizing news. In just eight hours the subject of all of his brooding, hating, and plotting would stand on the very stone steps where he now sat. This was the catalyst Booth needed to prompt him to action. Here. Of all places, Lincoln was coming here. Booth knew the layout of Ford’s intimately: the exact spot on Tenth Street where Lincoln would step out of his carriage; the place the president sat every time he came to the theatre; the route through the theatre that Lincoln would walk and the staircase he would ascend to the box; the dark, subterranean passageway beneath the stage; the narrow hallway behind the stage that led to the back door that opened to Baptist Alley; and how the president’s box hung directly above the stage. Booth had played here before, most recently in a March 18 performance as Pescara in The Apostate.

And Booth, although he had never acted in it, also knew Our American Cousin—its duration, its scenes, its players, and, most important, as it would turn out, the number of actors onstage at any given moment during the performance. It was perfect. He would not have to hunt Lincoln. The president was coming to him. But was there enough time to make all the arrangements? The checklist was substantial: horses; weapons; supplies; alerting his fellow conspirators; casing the theatre; so many other things. He had only eight hours. But it was possible. If luck was on his side, there was just enough time. Whoever told Booth about the president’s theatre party had unknowingly activated in his mind an imaginary clock that, even as he sat on the front step of Ford’s, chuckling aloud as he read his letter, began ticking down, minute by minute. He would have a busy afternoon.

At the cabinet meeting Lincoln was jubilant—everyone in attendance, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, and the secretaries of the Treasury, the Interior, and the Post Office and the attorney general—noticed Lincoln’s good mood. Welles, a faithful diarist, preserved an account of the gathering. Lincoln expected more good news from other battle fronts.

“The President remarked that it would, he had no doubt, come soon, and come favorable, for he had last night the usual dream which he had preceding nearly every great and important event of the War. Generally the news has been favorable which succeeded this dream, and the dream itself was always the same. I inquired what this remarkable dream could be. He said it related to your (my) element, the water; that he seemed to be in some singular, indescribable vessel, and that was moving with great rapidity towards an indefinite shore. That he had this dream preceding Sumter, Bull Run, Antietam, Gettysburg, Stone River, Vicksburg, Wilmington, etc.”

General Grant interrupted Lincoln and joked that Stone River was no victory, and that “a few such fights would have ruined us.”

“I had,” the president continued, “this strange dream again last night, and we shall, judging from the past, have great news very soon. I think it must be from Sherman. My thoughts are in that direction, as are most of yours.”

Lincoln had always believed in, and sometimes feared, the power of dreams. On June 9, 1863, while he was visiting Philadelphia, he sent an urgent telegram to Mary Lincoln at the White House, warning of danger to their youngest son: “Think you better put ‘Tad’s’ pistol away. I had an ugly dream about him.” And in April 1848, when he was a congressman in Washington, he wrote to Mary about their oldest son, Robert: “I did not get rid of the impression of that foolish dream about dear Bobby till I got your letter.”

After the meeting adjourned, the president followed his usual routine: receiving a variety of friends, supplicants, and favor seekers; reading his mail; and catching up on correspondence and paperwork. He was eager to wind up business by 3:00 P.M. for an appointment he had with his wife, Mary. There was something he wanted to tell her.

“Your favorite, General Grant, is going to be in the theatre tonight; and if you want to see him,” Ford cautioned, “you had better to go get a seat.”

Ferguson took advantage of the tip: “I went and secured a seat directly opposite the President’s box, in the front of the dress circle.” Ferguson booked seats 58 and 59 at the front corner of the house near stage right. The restaurateur didn’t want the best view of the play, but the best view of Lincoln and Grant.

James Ford walked to the Treasury Department a few blocks away to borrow several flags to decorate the president’s box. Returning to the theatre, his arms wrapped around a bundle of brightly colored cotton and silk bunting, he bumped into Booth, who had just left Ford’s, at the corner of Tenth and Pennsylvania, where they exchanged pleasantries. Booth saw the red, white, and blue flags, confirmation of the president’s visit tonight.

A few blocks away, on D Street near Seventh, at J. H. Polkinhorn and Son, Printers, pressmen began setting the type for the playbill that would advertise tonight’s performance. Once newsboys hit the streets with the afternoon and evening papers, the ad for Our American Cousin caught the eye of many Washingtonians eager to see General Grant.

Dr. Charles A. Leale, a twenty-three-year-old U.S. Army surgeon on duty at the wounded commissioned officers’ ward at the Armory Square Hospital in Washington, heard that President Lincoln and General Grant would be attending the play. He decided to attend. Three days prior, on the night of April 11, Leale, while taking a walk on Pennsylvania Avenue, encountered crowds of people walking toward the White House. He followed them there and arrived just as Lincoln commenced his remarks. Leale was moved: “I could distinctly hear every word he uttered, and I was profoundly impressed with his divine appearance as he stood in the rays of light which penetrated the windows.” The news that Lincoln was coming to Ford’s Theatre gave the surgeon “an intense desire again to behold his face and study the characteristics of the ‘Savior of his Country.’”

Lincoln’s box at Ford’s was festooned with flags and a framed engraving of George Washington. The box office manager prepared for a run on tickets when he went on duty at 6:30 P.M.

Later, witnesses remembered seeing Booth at several places in the city that day, but none of his movements created suspicion. Why should they? Nothing Booth did seemed out of the ordinary that afternoon. He talked to people in the street. He arranged to pick up his rented horse. Between 2:00 and 4:00 P.M., Booth rode up to Ferguson’s restaurant, stopping just below the front door. Ferguson stepped outside onto his front porch and found his friend sitting on a small, bay mare. James L. Maddox, property man at Ford’s, stood beside the horse, one hand on its mane, talking to Booth. “See what a nice horse I have got!” boasted the actor. Ferguson stepped forward for a closer look. “Now, watch,” said Booth, “he can run just like a cat!” At that, Ferguson observed, Booth “struck his spurs into the horse, and off he went down the street.”

At about 4:00 P.M., Booth returned to the National Hotel, walked to the front desk, and spoke to clerks George W. Bunker and Henry Merrick. Three days later a New York Tribune reporter described the encounter:

[He] made his appearance at the counter … and with a nervous air called for a sheet of paper and an envelope. He was about to write when the thought seemed to strike him that someone around him might overlook his letter, and, approaching the door of the office, he requested admittance. On reaching the inside of the office, he immediately commenced his letter. He had written but a few words when he said earnestly, “Merrick, is the year 1864 or ‘65?” “You are surely joking, John,” replied Mr. Merrick, “you certainly know what year it is.” “Sincerely, I am not,” he rejoined, and on being told, resumed writing. It was then that Mr. Merrick noticed something troubled and agitated in Booth’s appearance, which was entirely at variance with his usual quiet deportment. Sealing the letter, he placed it in his pocket and left the hotel.

On his way out of the National, Booth asked George Bunker if he was planning on seeing Our American Cousin at Ford’s, and urged Bunker to attend: “There is going to be some splendid acting tonight.”

Around 4:00 P.M., the actor John Matthews, who would be playing the part of Mr. Coyle in tonight’s performance, met Booth on horseback on Pennsylvania Avenue, at the triangular enclosure between Thirteenth and Fourteenth streets, not far from the Willard Hotel. “We met,” recalled Matthews, “shook hands, and passed the compliments of the day.” A column of Confederate prisoners of war had just marched past, stirring up a dust cloud in their wake.

“John, have you seen the prisoners?” Matthews asked. “Have you seen Lee’s officers, just brought in?”

“Yes, Johnny, I have.” Booth raised one hand to his forehead in disbelief and then exclaimed, “Great God, I have no longer a country!”

Matthews, observing Booth’s “paleness, nervousness, and agitation,” asked, “John, how nervous you are, what is the matter?”

“Oh no, it is nothing. Johnny, I have a little favor to ask of you, will you grant it?”

“Why certainly,” Matthews replied. “What is it?”

“Perhaps I may have to leave town tonight, and I have a letter here which I desire to be published in the National Intelligencer; please attend to it for me, unless I see you before ten o’clock tomorrow; in that case I will see to it myself.” Matthews accepted the sealed envelope and slipped it into a coat pocket.

As Booth and Matthews talked, Matthews spotted General Grant riding past them in an open carriage with his baggage. He appeared to be leaving town.

“There goes Grant. I thought he was to be coming to the theatre this evening with the President.”

“Where?” Booth exclaimed.

Matthews recalled: “I pointed to the carriage; he looked toward it, grasped my hand tightly, and galloped down the avenue after the carriage.”

When Booth caught up to the Grants and rode past their carriage, Julia Grant thought of something that had happened earlier in the day. She was at lunch at the Willard Hotel with General Rawlins—one of Grant’s top aides—Mrs. Rawlins, and the Rawlinses’ daughter, when four men entered the dining room and occupied a nearby table. One of the men would not stop staring at her, and Julia and Mrs. Rawlins both found the whole group “peculiar.” Now, a few hours later, Booth reminded her of the unpleasant incident when he caught up to their carriage. “As General Grant and I rode to the depot, this same dark, pale man rode past us at a sweeping gallop on a dark horse…. He rode twenty yards ahead of us, wheeled and returned, and as he passed us both going and returning, he thrust his face quite near the General’s and glared in a disagreeable manner.” She was sure that it was the same man from Willard’s.

The sight of the Grants must have disappointed Booth. Their carriage, loaded with baggage, was heading toward the train station. They were leaving town. They must have canceled their engagement at Ford’s Theatre. If General Grant was not attending Our American Cousin tonight, did that mean...