1

HEART OF DARKNESS

As an undergraduate at St. Hilda’s College, Oxford, I studied English literature. Our first term was devoted to the Victorians. We loved them. We swept happily through the Brontë sisters, Thomas Hardy, Dickens, and even George Eliot (“Jane Austen, but with peasants,” as my friend Joanna put it). But our second term was devoted to modernism, and we began with Heart of Darkness, which was published in 1899. Here, our ride came to a sad halt.

I tried again and again, but I couldn’t seem to get past the first six or seven pages. Reading this difficult novella felt like climbing a slippery cliff: there was nothing to grab on to. Occasionally I thought I’d found a foothold, but the next moment I’d feel myself falling again, unable to focus, losing my place. Everything was “impossible,” “impenetrable,” “implacable.” I’d lie on my bed with the book in my hand, and suddenly I’d be miles away, thinking of a dream I’d had, or wondering what to wear. Whenever I tried to pick up the story’s thread again, I’d be lost. In fact, there hardly seemed to be a story at all. It was horribly frustrating. By the day of my tutorial, I’d “got to the end” of the novella only in the sense that I’d looked at the words and turned the pages until there were no more of them to turn.

There was only one scene I could remember, and I could remember it only because it came early in the story, and I’d found myself reading it over and over again. The protagonist, Marlow, has been hired to replace a steamship captain who’s been killed in the Congo after “a scuffle with the natives.” Before leaving Europe, Marlow visits his employer’s offices to meet the manager and fill out some final paperwork. There’s a mounting sense of foreboding. The offices are located on a “narrow and deserted street in deep shadow” and “dead silence.” Marlow enters through “immense double doors standing ponderously ajar,” climbs a staircase, and comes to a waiting room where two women dressed in black guard the door to the manager’s office. The atmosphere gets even darker. “I began to feel slightly uneasy,” confesses Marlow. “I am not used to such ceremonies, and there was something ominous in the atmosphere. It was just as though I had been let into some conspiracy—I don’t know— something not quite right; and I was glad to get out.”

But the interview isn’t over. The company requires Marlow to have a consultation with a doctor, who takes his pulse, then asks him, “with a certain eagerness,” if he’d mind having his head measured. Marlow, rather surprised, agrees. The doctor then produces a pair of calipers and proceeds to appraise various dimensions of his skull, taking careful notes all the while.

“I always ask leave, in the interests of science, to measure the crania of those going out there,” says the doctor.

“And when they come back too?” Marlow asks him.

“Oh, I never see them,” the doctor replies, “and, moreover, the changes take place inside, you know.”

I liked the agitated, portentous tone of this scene. I liked the idea of someone having their head measured before going on a dangerous journey, and I liked the idea that they never come back. The rest of the book made no sense to me.

But during my tutorial, everything changed. My tutor, Lyndall Gordon, sitting in a deep armchair, brought the story to life. The Heart of Darkness she described that rainy afternoon sounded nothing like the dry tome I’d been struggling with. Her Heart of Darkness was a gruesome, disturbing story about cannibals, slaves, nightmares, morbid rituals, and severed heads on stakes.

“It’s just your cup of tea,” she said, in her lovely South African accent, knowing how much I loved horror stories. This Heart of Darkness was immeasurably more mysterious and compelling than the book I’d been trying to read. How could I have missed those severed heads on stakes?

When I’d first confessed to Lyndall—who shaped and framed my love of literature—that I wanted to be an academic like her, she shook her head.

“Oh, no, I don’t see you in that role at all,” she said.

I was surprised and dismayed, but I can see why she responded as she did. I even saw it at the time. I had an enormous capacity for self-discipline, but I didn’t identify with authority or with established ways of doing things. I could be oppositional, sometimes to an extreme degree. I was odd and unpredictable, and although I could certainly be described as eccentric, I wasn’t eccentric in the academic way, in the sense that I wasn’t detail oriented. I didn’t care enough about getting the footnotes right.

Looking back, I wasn’t ready for Heart of Darkness. Lyndall understood this. The novella seemed complicated, she told me, if you weren’t used to reading prose like Conrad’s. You had to immerse yourself in it to really understand how it worked.

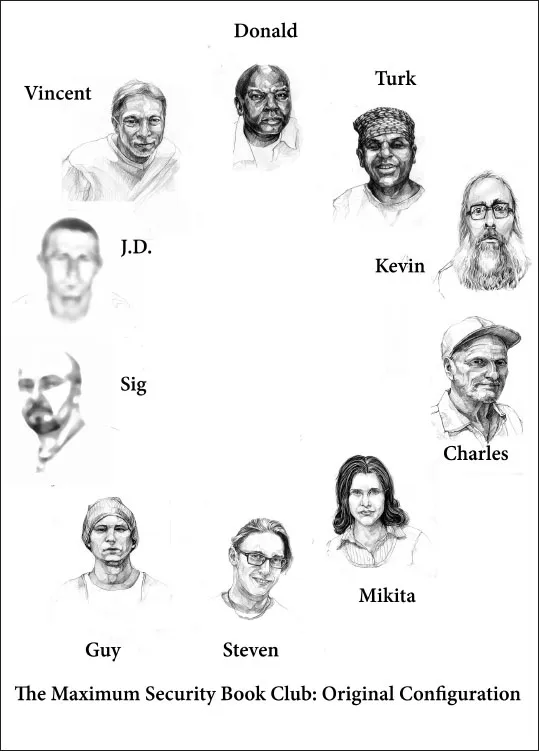

Illustration of book club by Jess Bastidas

I went back to my room fired up with the desire to try again. I did. It was still impossible. But now it was interesting.

Over the past twenty-five years, I’ve read this book many times, and now I understand that, just as certain pieces of music can’t be understood until you’ve heard them over and over again, some books need to be read more than once, and Heart of Darkness is one of them. Every time I read it, I seem to find a new and amazing passage I hadn’t really paid attention to before. This slim novella seems magically self-renewing, like the loaves and the fishes. I know it’s a book I’d want in my cell if I were in prison, which is one of the reasons why I chose it for the book club. Another reason I chose it is because I felt that if the men managed to struggle through Conrad’s notoriously complex sentences, they might enjoy the gruesome, disturbing parts of the story. Perhaps they might even find some connections between Marlow’s expedition into Africa and their own experiences at JCI and other prisons. But I never lost sight of the fact that it had taken me a long time to love it. This wasn’t a book that opened itself up on first reading, and I hoped the prisoners would be patient. After all, I thought, the one thing they had plenty of was time.

JANUARY 9, 2013

By the time the book club had its first meeting, I was starting to feel a little more confident walking through the prison compound. Officers would recognize me from the classes I’d taught before and give me a nod; the sally port would open automatically as I approached with my escort, and if I heard someone yell a greeting on the compound, I’d give them a vague, friendly wave rather than staring blankly ahead, as I used to do. I was no longer a nervous, naïve outsider, and I was cautiously optimistic for my next venture. Vincent had selected nine men for the book club whom he knew to be trustworthy and intelligent, and I’d asked him, when he enrolled them, to lay down the ground rules: no disrespect, no interrupting, no inappropriate behavior, and no reading ahead.

Heart of Darkness begins with five men on the deck of a yacht anchored in the Thames, waiting for the tide to turn. Marlow, sitting cross-legged by the mast, starts to tell a story. This opening scene came to my mind when I got to our classroom for the first session of the group and saw the men had set up a circle of chairs in preparation for our meeting. A central chair, saved for me, formed the anchor. Over the months and years I spent with this group of men, I noticed that—until we came to the final book—they always sat faithfully in the place they chose that very first day. Clearly, these were men who were accustomed to sticking to a routine and to carving out the boundaries of their own space, however small.

I noticed most of the men were wearing brown Timberland work boots, and a couple of them had small cartons of milk or orange juice on the floor by their chairs. A friendly Labrador retriever lay at the feet of the young man on my left, Steven, who was taking part in a program called Canine Partners for Life, which places dogs with responsible prisoners who train them for a year to work as service animals. Steven’s dog was already so well trained he wouldn’t even touch a treat placed on his paw until given the go-ahead. Confusingly, the dog was also named Steven. (The dogs’ names are chosen by their sponsors, and this particular sponsor was financing a pair of dogs named in honor of his two sons.)

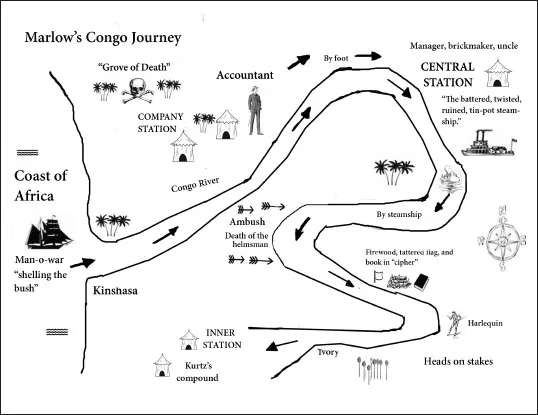

I began the discussion by telling the men a little about the life of Joseph Conrad and his ordeal in the Congo. I’d brought along a copy of his Congo Diary, and I read them the description of his journey upriver: dead bodies in his path, a skeleton tied to a tree, the grave of a nameless white man (a pile of stones in the sign of a cross). Then his body started to fail him. I read a passage from a letter he wrote to his aunt: “My health is far from good. In going up the river I suffered from fever four times in two months, and then at the Falls . . . I suffered an attack of dysentery lasting four days.” Back in London after hovering at the brink of death, he was hospitalized with gout, neuralgia, malaria, and all the symptoms of physical and mental breakdown. “Utterly demoralized,” he wrote in his journal. “I had the time to wish myself dead over and over again with perfect sincerity.” He never fully recovered from the expedition, and was plagued for the rest of his life by recurrent fever and attacks of depression.

I handed each of the men a copy of Heart of Darkness, a barebones edition of the novella that I’d bought online (ten copies for twelve dollars, including shipping). I also handed them each a copy of a rather primitive map I’d made of Marlow’s journey upriver and back. I suggested we go around the circle, each of the men reading aloud from the novel in turn, as much as they felt like reading. (I offered the chance to take a pass, but no one did.)

Kevin, a middle-aged man with thick glasses and a bushy gray beard, volunteered to go first. He began reading aloud with a grim, conscious effort, straining to pronounce the words, which came slowly and with difficulty. Everyone seemed relieved when he stopped after a few lines. Next was Vincent. Putting on a pair of large, thick-lensed reading glasses, he picked up where Kevin had left off, and read articulately, at an even pace. Next came Steven. Six feet tall and two hundred pounds, his shoulders pumped up with prison muscle, Steven was all youth and energy. He read in a loud voice and squirmed around in his seat while he did so, bouncing his feet up and down on the floor. His section included a famously impressionistic passage in which Marlow’s method of storytelling is described as “one of these misty halos that sometimes are made visible by the spectral illumination of moonshine.” When he came to these lines, Steven’s whole body twitched visibly. He looked up at me.

“I love that!” he said.

Later in Heart of Darkness, Marlow, deep in the uncharted Congo, comes across a twenty-five-year-old Russian, the son of an archpriest, dressed in a harlequin’s colorful patchwork. Marlow is astonished to find him there. “His very existence was improbable, inexplicable . . .” This wasn’t far from how I felt about Steven. To meet someone who’s always upbeat is rare enough in the outside world; in a maximum security prison, it felt marvelously unlikely. I’d have expected anyone in Steven’s circumstances to be cold, guarded, and cynical; but, like the Russian harlequin, “there he was gallantly, thoughtlessly alive, to all appearance indestructible . . .”

STEVEN

Photo of Steven courtesy of Jessup Correctional Institution

Steven was a real chatterbox: he found it difficult to keep quiet for much longer than ten minutes at a stretch. When he wasn’t speaking, he was writhing and fidgeting. (He told me that he’d been diagnosed with ADD/ADHD when he was five, but thought it was “bullshit.”) When I got to know him better, I learned there wasn’t much point starting the discussion until he got there. His energy charged the atmosphere. He’d walk into the room with his big grin, his blue eyes gleaming. He liked to change up his hairstyle. Some days his light brown hair was combed flat, sometimes it was tucked under a cap or bandana, or, like today, it would be spiked into a short Mohawk. He always had a cheerful comment to brighten the room. “Hello! It’s Wednesday, my favorite day of the week,” he’d say. “The sun’s shining,” or “It’s spaghetti for dinner,” or “They’re showing the Winter Olympics on TV next week.” He’d often thank me after class too: “Hey, I just want to say I really felt like I learned a lot today.” Every man played a role in the book club, but Steven was its beating heart.

And his enthusiasm wasn’t directed only at the reading group. Steven threw himself into everything he did: college classes, playing his guitar, meditation, soccer, video games, Dungeons & Dragons, poker—even, believe it or not, the prison food. Although he kept up conscientiously with the books I assigned, he also read fiction by Lovecraft, Tolkien, and George R. R. Martin, and confessed to having a soft spot for Anne Rice’s erotic fantasies. He corresponded with a mentor who taught him about occult subjects—“philosophy, psychology, how to control your own actions and the inner workings of your mind.” Steven was a student of Magick, which he described to me as “understanding the different natures of energy types and thought patterns to be aware and prepared to act effectively in given situations.”

Yet it wasn’t only his youth and natural temperament that kept his spirits high. It was also...