![]()

PART ONE

THE MYSTERY OF THE MISSING FOSSILS

![]()

1

DARWIN’S NEMESIS

When Charles Darwin finished his famous book, he thought that he had explained every clue but one.

By anyone’s measure, On the Origin of Species was a singular achievement. Like a great Gothic cathedral, the ambitious work integrated many disparate elements into a grand synthesis, explaining phenomena in fields as diverse as comparative anatomy, paleontology, embryology, and biogeography. At the same time, it was impressive for its simplicity. Darwin’s Origin explained many classes of biological evidence with just two central organizing ideas. The twin pillars of his theory were the ideas of universal common ancestry and natural selection.

The first of these pillars, universal common ancestry, represented Darwin’s theory of the history of life. It asserted that all forms of life have ultimately descended from a single common ancestor somewhere in the distant past. In a famous passage at the end of the Origin, Darwin argued that “all the organic beings which have ever lived on this earth have descended from some one primordial form.”1 Darwin thought that this primordial form gradually developed into new forms of life, which in turn gradually developed into other forms of life, eventually producing, after many millions of generations, all the complex life we see in the present.

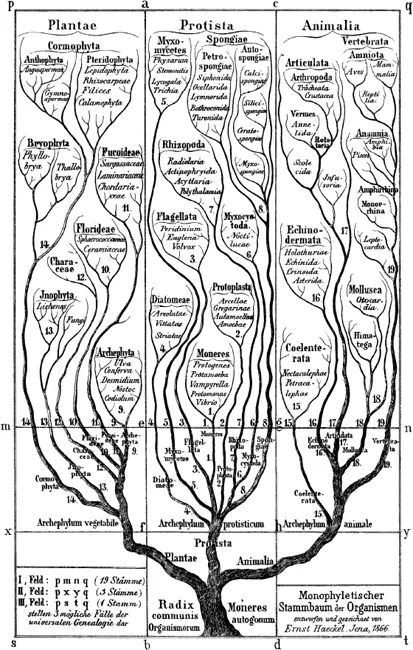

Biology textbooks today usually depict this idea just as Darwin did, with a great branching tree. The trunk of Darwin’s tree of life represents the first primordial organism. The limbs and branches of the tree represent the many new forms of life that developed from it (see Fig. 1.1). The vertical axis on which the tree is plotted represents the arrow of time. The horizontal axis represents changes in biological form, or what biologists call “morphological distance.”

FIGURE 1.1

Darwin’s evolutionary tree of life, as depicted by the nineteenth-century German evolutionary biologist Ernst Haeckel.

Biologists often call Darwin’s theory of the history of life “universal common descent” to indicate that every organism on earth arose from a single common ancestor by a process of “descent with modification.” Darwin argued that this idea best explained a variety of biological evidences: the succession of fossil forms, the geographical distribution of various species (such as Galápagos finches), and the anatomical and embryological similarities among otherwise highly distinct organisms.

The second pillar of Darwin’s theory affirmed the creative power of a process he called natural selection, a process that acted on random variations in the traits or features of organisms and their offspring.2 Whereas the theory of universal common descent postulated a pattern (the branching tree) to represent the history of life, Darwin’s idea of natural selection referred to a process that he said could generate the change implied by his branching tree of life.

Darwin formulated the idea of natural selection by analogy to a well-known process, that of “artificial selection” or “selective breeding.” Anyone in the nineteenth century familiar with the breeding of domestic animals—dogs, horses, sheep, or pigeons, for example—knew that human breeders could alter the features of domestic stock by allowing only animals with certain traits to breed. A sheepherder from the north of Scotland might breed for a woollier sheep to enhance its chances of survival in a cold northern climate (or to harvest more wool). To do so, he would choose only the woolliest males and woolliest ewes to breed. If generation after generation he continued to select and breed only the woolliest sheep among the resulting offspring, he would eventually produce a woollier breed of sheep. In such cases, “the key is man’s power of accumulative selection,” wrote Darwin. “Nature gives successive variations; man adds them up in certain directions useful to him.”3

Darwin noted that pigeons have been coaxed into a dizzying variety of breeds: the carrier, with its elongated eyelids and a “wide gape of mouth”; the “short-faced tumbler,” with its “beak in outline almost like that of a finch”; the common tumbler, with its penchant for flying in close formation and “tumbling in the air head over heels”; and, perhaps strangest of all, the pouter, with its elongated legs, wings, and body overshadowed by its “enormously developed crop, which it glories in inflating” for its astonished patrons.4

Of course, pigeon breeders achieved these startling metamorphoses by carefully sifting and selecting. But, as Darwin pointed out, nature also has a means of sifting: defective creatures are less likely to survive and reproduce, while those offspring with beneficial variations are more likely to survive, reproduce, and pass on their advantages to future generations. In the Origin, Darwin argued that this process, natural selection acting on random variations, could alter the features of organisms just as intelligent selection by human breeders can. Nature itself could play the role of the breeder.

Consider once more our flock of sheep. Imagine that instead of a human selecting the woolliest males and ewes to breed, a series of very cold winters ensures that all but the very woolliest sheep in a population die. Now again only very woolly sheep will remain to breed. If the cold winters continue over several generations, will the result not be the same as before? Won’t the population of sheep eventually become discernibly woollier?

This was Darwin’s great insight. Nature—in the form of environmental changes or other factors—could have the same effect on a population of organisms as the intentional decisions of an intelligent agent. Nature would favor the preservation of certain features over others—specifically, those that conferred a functional or survival advantage upon the organisms possessing them—causing the features of the population to change. And the resulting change will have been produced not by an intelligent breeder choosing a desirable trait or variation—not by “artificial selection”—but by a wholly natural process. What’s more, Darwin concluded that this process of natural selection acting on randomly arising variations had been “the chief agent of change” in generating the great branching tree of life in all its variety.

On the Origin of Species seized the attention of the scientific community like a thunderclap. Darwin’s analogy to artificial selection was powerful, his proposed mechanism of natural selection and random variation easily grasped, and his skill in dispensing with potential objections unrivalled. Moreover, the explanatory scope of his argument for universal common descent constituted something of a tour de force. By the close of the Origin, it seemed to many that Darwin had dispensed with every conceivable objection to his theory but one.

THE ANOMALY: DARWIN’S DOUBT

Despite the scope of his synthesis, there was one set of facts that troubled Darwin—something he conceded his theory couldn’t adequately explain, at least at present. Darwin was puzzled by a pattern in the fossil record that seemed to document the geologically sudden appearance of animal life in a remote period of geologic history, a period that at first was commonly called the Silurian, but later came to be known as the Cambrian.

During this geological period, many new and anatomically sophisticated creatures appeared suddenly in the sedimentary layers of the geologic column without any evidence of simpler ancestral forms in the earlier layers below, in an event that paleontologists today call the Cambrian explosion. Darwin frankly described his concerns about this conundrum in the Origin: “The difficulty of understanding the absence of vast piles of fossiliferous strata, which on my theory were no doubt somewhere accumulated before the Silurian [i.e., Cambrian] epoch, is very great,” he wrote. “I allude to the manner in which numbers of species of the same group suddenly appear in the lowest known fossiliferous rocks.”5 The sudden appearance of animals so early in the fossil record did not easily accord with Darwin’s new theory of gradual evolutionary change, and there was one scientist who would not let him forget it.

THE ANTAGONIST

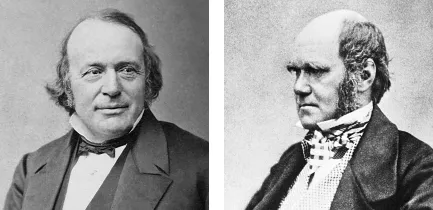

Swiss-born paleontologist Louis Agassiz, of Harvard University, was one of the best-trained scientists of his age, and he knew the fossil record better than any man alive. Hoping to enlist Agassiz as an ally, Darwin sent him a copy of On the Origin of Species and asked him to consider the argument with an open mind (see Fig. 1.2). One can almost see the great, aging naturalist receiving the unremarkable package from the postman, unwrapping the small green volume that had stirred such a tempest on both sides of the Atlantic. Perhaps he retired to his study the better to concentrate, scrutinizing the book’s prepossessing title, recalling what he had already heard about the work. He read the book with deep interest, making notes in the margin as he moved through it, but in the end his verdict would disappoint its author. Agassiz concluded that the fossil record, particularly the record of the explosion of Cambrian animal life, posed an insuperable difficulty for Darwin’s theory.

FIGURE 1.2

Figure 1.2a (left): Louis Agassiz. Figure 1.2b (right): Charles Darwin.

THE TWO-PRONGED CHALLENGE

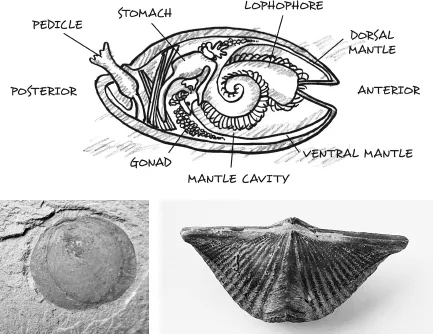

To see why, consider brachiopods and trilobites, two of the best-documented creatures in the Cambrian fossil record by 1859. The brachiopod (see Fig. 1.3), with its two shells, looks like a clam or an oyster, but is very different inside. As shown in the accompanying figure, it possesses a gonad, mantle, mantle cavity, anterior body wall, body cavity, gut, and lophophore, the last of which is a feeding organ like a ring of tentacles, usually in the shape of a coil or horseshoe, with a mouth inside the ring of tentacles, and an anus outside. The brachiopod exhibits a highly complex overall body plan, with many individually complex and functionally integrated anatomical systems and parts. Its tentacles, for instance, are covered by cilia precisely arranged to generate and direct a current of water toward the mouth.6

FIGURE 1.3

Figure 1.3a (top): Brachiopod internal anatomy. Figure 1.3b (bottom, left): Brachiopod fossil showing remains of internal structure. Courtesy Paul Chien. Figure 1.3c (bottom, right): Fossil showing exterior structure of brachiopod shell. Courtesy Corbis.

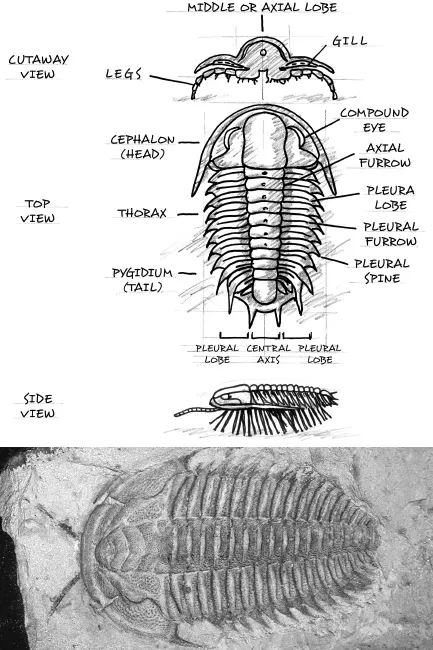

FIGURE 1.4

Figure 1.4a (top): Trilobite anatomy. Figure 1.4b (bottom): Trilobite fossil of the species Kuanyangia pustulosa. Courtesy Illustra Media.

Even more sophisticated was the trilobite (see Fig. 1.4), with its three longitudinal lobes across its head (a raised middle lobe and a flatter pleural lobe to either side) and a body divided into three parts—head, chest, and tail, the former two consisting of as many as thirty segments. It had a pair of legs for every pleural groove and another three pairs for the head. Most dramatic of all were the compound eyes found on even some of the very early trilobites—eyes that afforded these not so primitive animals a 360-degree field of vision.7

The abrupt appearance of such complex anatomical designs presented a challenge to each of the two main parts of Darwin’s theory of evolution.

THE CAMBRIAN EXPLOSION AND THE ACTION OF NATURAL SELECTION

The Cambrian fossil evidence represented a significant challenge to Darwin’s claim that natural selection had the capacity to produce novel forms of life. As Darwin described it, the ability of natural selection to produce significan...