IT WAS THE DAY after Christmas, 1880, at approximately 4:00 P.M., when a mule-drawn wagon accompanied by five armed horsemen rapidly approached the outskirts of Las Vegas in the Territory of New Mexico. The leader of the men on horseback rode stoop shouldered, a natural consequence of his six-foot-four-inch frame. He was as thin as a rail, and even as bundled up as he was, he seemed to be all arms and legs. He had a dark mustache, light gray eyes, and a swarthy face that showed the years he had spent on the open range of Texas and New Mexico.

Seated in the wagon were four dirty, trail-worn men in handcuffs and shackles. They were the lanky man’s prisoners, and one of them was hardly out of his teens. As the wagon bounced along, the young outlaw, his blue eyes dancing about, broke into an occasional smile or burst out in a hearty laugh, exposing two buckteeth, a feature that was unattractive in most people, but for this young man seemed to add to his charm. The boyish prisoner and the tall lawman, although complete opposites, shared a common destiny. Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett had no way of knowing it, but they were fated to be forever linked in both life and death.

The Las Vegas that spread out before them was really two towns, one old and the other new. The old town had been established on the Santa Fe Trail in 1835 along the Gallinas River (what easterners would call a creek). The settlement got its name from the river’s broad grassy valley: las vegas—“the meadows.” The new town sprang up forty-four years later when the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad came through a mile away on the east side of the Gallinas. In 1880, Las Vegas, the county seat of San Miguel County, numbered six thousand people, mostly Hispanos. The city’s numerous hell-raisers, mostly Anglos, resided in New Town, where saloons, dance halls, and gambling establishments ran day and night.

The Las Vegas Daily Optic reported: “Yesterday afternoon the town was thrown into a fever of excitement by an announcement that the ‘Kid’ and other members of his gang of outlaws had been captured, and were nearing the city.” Sheriff Garrett’s party had come up the old Santa Fe Trail. Their route to the stone jailhouse on Valencia Street took them across one end of Old Town’s plaza, where most people got their first glimpse of the prisoners.

Billy beamed at the crowd and spotted Dr. John H. Sutfin, owner of the Grand View Hotel. “Hello, Doc!” he called out. “Thought I jes drop in an’ see how you fellers in Vegas air behavin’ yerselves.”

The throng of gawkers, growing by the minute, followed the wagon down the muddy street to the jail, where the prisoners and guards promptly disappeared inside. A reporter for the Las Vegas Gazette cornered the thirty-year-old Garrett for a few minutes, hoping he could get the thrilling narrative of the gang’s capture. Garrett almost immediately passed off the excited journalist to a posse member named Manuel Brazil, saying Brazil “knew all the particulars.”

Monday morning’s frigid air did not stop the curious townspeople from gathering around the jail, hoping to glimpse the desperadoes: Billy the Kid, Billy Wilson, Dave Rudabaugh, and Tom Pickett, the latter being a former Las Vegas policeman. Nearly everyone knew something about Billy—even if it was only that the twenty-one-year-old had sent far too many men to their graves. His most infamous crime was the killing of Sheriff William Brady and his deputy, George Hindman, in an ambush in Lincoln during the Lincoln County War. The Kid was not the only one who fired on the sheriff and his deputies that day, but he had walked away with a murder indictment. And this murder charge was the one he feared most. In the spring of 1879, Governor Lew Wallace met with Billy in order to draw out his eyewitness testimony in another highly charged Lincoln County murder case. In exchange for this testimony, Billy was to be offered a pardon. The Kid did his part, but the pardon never came. Now Billy knew it was only a matter of time before he would face a hangman’s noose.

Michael Cosgrove, the Las Vegas mail contractor, pushed through the crowd carrying four bundles under his arms. They contained new suits of clothes for the prisoners, and the Irish-born Cosgrove remarked that he wanted “to see the boys go away in style.” The town’s two competing newspapers, the Gazette and the Optic, both managed to get reporters into Sheriff Desiderio Romero’s jail that morning, but the Gazette’s man got the best story. The reporter watched as a blacksmith took his hammer and cold chisel and began carefully shearing the rivets of the shackles and bracelets worn by the Kid and Billy Wilson, who were chained together. The irons had to come off before the prisoners could change their clothing. Wilson was glum and quiet, but the Kid was acting “light and chipper…very communicative, laughing, joking and chatting with the bystanders.”

“You appear to take it easy,” the Gazette reporter said to the Kid.

“Yes! What’s the use of looking on the gloomy side of everything,” Billy replied. “The laugh’s on me this time.”

The Kid cast his eyes around and began kicking the toes of his boots on the stone floor to warm his feet. “Is the jail in Santa Fe any better than this?” he asked. “This is a terrible place to put a fellow in.”

He asked this same question of everyone who came close to him, and they all told him the Santa Fe jail was not any better. Billy then shrugged his shoulders and said he would just have to put up with what he had to. The Kid may not have liked what was happening to him, but he was thrilled at all the attention he was getting. Being a celebrity suited him just fine.

“There was a big crowd gazing at me, wasn’t there,” Billy said, referring to the moment when the doors were opened to let the mail contractor in. “Well,” and here the Kid broke into a smile again, “perhaps some of them will think me half man now; everyone seems to think I was some kind of animal.”

Not surprisingly, the Gazette reporter seemed to like the youthful outlaw, and he wrote the best (and most quoted) description of Billy:

When the blacksmith popped the last rivet, and the Kid’s cuffs fell to the ground, Billy stretched and rubbed his sore wrists. “I don’t suppose you fellows would believe it but this is the first time I ever had bracelets on,” he said. “But many another better fellow has had them too.” Then, as Billy and Wilson were ushered back into their cell, the Kid said a few words about the man who had tracked him down and put him in irons. “They say, ‘a fool for luck and a poor man for children’—Garrett takes them all in.”

Garrett had originally planned to take the prisoners to the depot and get them on a train for Santa Fe (all except Tom Pickett, for whom he had no federal warrant), but when he and his deputies arrived at the jail shortly after breakfast, only the Kid and Wilson were led out. Sheriff Romero refused to turn over Dave Rudabaugh, who eight months earlier had shot jailer Lino Valdez while attempting to break out a friend from this very same lockup. Romero, as well as the majority of the townspeople, wanted to see Rudabaugh tried in Las Vegas for this murder.

Garrett had expected this, but he had also promised Rudabaugh he would get him safely to Santa Fe. A heated discussion ensued. Garrett reminded the sheriff that he was a deputy U.S. marshal, and his federal warrant trumped their murder charges. Garrett may have been a soft-spoken man under normal circumstances, but he had no trouble letting it be known that he was going to get his way: “[H]e was my prisoner, I was responsible for him, and intended to have him,” he wrote later. Romero and his men reluctantly released Rudabaugh, but they were not through just yet.

Prisoners and guards squeezed into two or three hacks (an open wagon with three bench seats) for the short trip to the depot in New Town. Garrett’s posse included Deputies Barney Mason, Frank Stewart, Jim East, Tom Emory, U.S. Marshal James W. Bell, and contractor Cosgrove. At the depot, they found the westbound train waiting on the tracks, its passengers completely unaware that the noted desperado Billy the Kid was about to join them.

Seated in the train’s smoking car that day was Benjamin S. Miller, a twenty-nine-year-old native of New York State who had entered the cattle business near Medicine Lodge, Kansas. He had gone out west because he was as interested in playing cowboy and shooting wild game as he was in seeking his fortune (which he eventually found). While recently visiting Wichita, Miller met a friend who gave him a Santa Fe railroad pass that was expiring in a few days. “Take it, and go while it lasts,” his friend had urged. Miller did just that, intending to travel as far west as possible on the Santa Fe line and return within the allotted time. Because the pass was made out in his friend’s name, though, Miller had to bend the truth with the conductors, but without photo IDs in that era, this was easily done, and Miller experienced not the slightest difficulty, enjoying his trip immensely—until the train stopped at Las Vegas.

Garrett and his deputies hurried their three prisoners down the track siding to the smoking car and quickly ushered them up its narrow steps. Miller and three miners, deeply absorbed in a game of cards, suddenly heard the clanking of chains entering their car. They looked up to see the lawmen and the shackled outlaws. The racket caused by the sheriff’s party was quickly followed by shouts from a crowd gathered just outside the car. Many of them were well armed, and some of these men began taking up positions behind a stack of railroad ties near the tracks. Garrett addressed the passengers in a loud but steady voice:

“Any of you people who don’t want to be in it, had better get out before I lock the car, as we are liable to have a hell of a fight in a few minutes.”

Garrett had hardly finished speaking when Miller saw two men jump out of their seats and dash for the adjoining car, not even stopping for their valises. He then watched in amazement as the three miners he was playing cards with pulled out an assortment of weapons.

“They offered me a big six-shooter,” Miller recalled, “but I declined.”

One of the deputies told the uneasy stockman that the crowd outside, largely Hispanos, wanted Dave Rudabaugh, and they were sure the mob was going to lynch the outlaw as soon as they got their hands on him. Garrett was not about to let that happen, not short of a bloodbath.

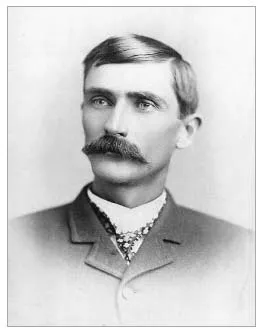

Pat Garrett, circa 1881.

Robert G. McCubbin Collection

“It seemed as if the fight would begin any minute,” Miller remembered, “and I expected to see the Mexicans fire into the car right away.” Miller moved to the opposite end of the coach and crouched behind a stove.

A group of men rushed to the front of the train and confronted the locomotive’s twenty-six-year-old engineer and fireman, Dan Daley.

One of them thrust a pistol in Daley’s face and shouted, “My father does not want this train to pull out of here.”

“And who is your father?” Daley asked.

“Sheriff Romero is my father.”

When Daley let some steam escape from the engine, the young man became agitated: “I don’t want to shed any blood, but if you try to pull out you will be a dead man.”

Daley kept the train parked.

Somehow, as ugly as things had gotten around the train, the Gazette’s reporter managed to get next to the smoking car where Billy was leaning out of a window, probably on the side opposite the mob.

“I don’t blame you for writing of me as you have,” he said. “You had to believe others’ stories; but then I don’t know as anyone would believe anything good of me anyway. I wasn’t the leader of any gang—I was for Billy all the time…. I found that there were certain men who wouldn’t let me live in the country and so I was going to leave. We had all our grub in the house when they took us in, and we were going to a place about six miles away in the morning to cook it and then ‘light’ out. I haven’t stolen any stock. I made my living by gambling but that was the only way I could live. They wouldn’t let me settle down; if they had I wouldn’t be here today.”

Billy cursed about the chains on his wrists and ankles and let it be known that he was anxious to take part in the fight that was brewing. “If I only had my Winchester,” he said, “I’d lick the whole crowd.”

Benjamin Miller remembered the great contrast between the noise outside the car and the quiet inside: “Nine men with cocked rifles sturdily standing off a mob of hundreds. Those men never flinched an iota. Such bravery, even to recklessness, was new to me.”

Sheriff Romero and his delegation, their pistols drawn, approached the car platform where Garrett stood and clambered up the steps. They made their blustery demand for Dave Rudabaugh, and Garrett simply replied, “Come and take him.” It was not a bluff, and it must have scared Romero out of his wits.

The towering Garrett then ordered the delegation to get down off the train, and they slunk back to the crowd empty-handed.

Garrett next turned to his prisoners, telling them that he and his deputies were going to fight back if anyone tried to enter the car. More important, he told the prisoners he would arm them if a gun battle broke out. He would need their help to defend the car.

The Kid’s eyes glistened at that. “All right, Pat,” he said. “All I want is a six-shooter. There is no danger, though. Those fellows won’t fight.”

Miguel Otero then addressed the mob. A stocky fellow, he was a forwarding and commission merchant and prominent political figure in the Territory. He urged the men to let Garrett carry out his official duty. Otero also cautioned them about the consequences of delaying the U.S. mail, but it is hard to imagine that a matter as small as that had much effect on those bent on seeing “Dirty Dave” hang.

The standoff on the tracks had now stretched to about forty-five minutes when postal inspector J. Fred Morley approached Garrett.

“I have been an engineer,” he told the lawman, “and if you will let me, I’ll slip down through the mob, get in the cab, pull the throttle open, and we’ll get out of here.”

“Good, go do it,” Garrett said.

Morley made his way to the locomotive, but he did more than simply pull the throttle open—he hit it wide open. The heavy wheels spun, grabbed hold, and the cars lurched ahead. The mob was stunned and did not move. Realizing there was nothing they could do to stop the train now, the men who were holding the locomotive’s engineer and fireman released their prisoners, who quickly jumped aboard the moving train.

“By the time we got to the end of the siding,” remembered Jim East, “it seemed like we were going a mile a minute, and the Mexicans stood there with their mouths open.”

The Gazette reporter watched as Billy, still leaning out his window, waved his hat, grandly inviting the reporter to call on him in Santa Fe. He then shouted “Adios” and disappeared.

In a...