- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

STILL ILL

The Smiths: The Queen Is Dead (Sire Records, 1986)

Benjamin Kunkel

Rosalind. They say you are a melancholy fellow. Jaques. I am so. I do love it better than laughing.

—from As You Like It

I must have been a child—logic insists on it, and snapshots show proof—but I retain hardly any sense of subjective continuity between then and now, and whenever I allude to the boy I was I feel slightly dishonest, as if I’m pretending to a personal acquaintance with someone I don’t actually know. Few of my boyish interests have survived, and even when it comes to, for instance, our family’s dogs, the Denver Broncos, and girls, at the time, far more has changed than has remained the same. Nothing, then, in my present incarnation seems to date from any earlier period than when I first found myself flipping my cassette of The Queen Is Dead back over to the A-side the moment the last, weird strains of “Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others” had faded out, and returning once more to the album’s opening song and title track. A hearty British woman’s voice, sampled from an old film, leads a chorus of “Take Me Back to Dear Old Blighty”; the apparently patriotic number is rudely dispatched by a peal of feedback; a murderous rhythm is set up on unaccompanied drums; the guitar begins woozily to wah-wah; a brushed cymbal shivers; the mean-spirited funk of the bass line kicks in; you hear that moan you’d recognize anywhere; the first moaned word is “farewell”; everything I feel in the way of snottiness, shyness, and distraught longing stands ready to be recognized by the ten unaccountably angry and joyous tracks before me; and, with that, I am tempted to say, my life as I know it begins.

In 1986 I was living with my family in the humdrum town of Eagle, Colorado. I had just become a teenager and was applying to prep schools in New England. I considered myself a rather tragic, intelligent, and solitary figure, and was accordingly full of fantasies of escape from the baffled cows and squinting hicks who swelled my middle school class. At the same time there was obviously something wrong with me, a basic temperamental deficiency that prevented me from taking life with that casualness, amounting almost to grace, displayed by normal people. Suicide or fame seemed likely destinies. Meanwhile I had picked up a bad case of Anglophilia; in one egregious instance, when I and a friend DJ’ed a middle school dance I delivered my patter in what I took to be a British accent. Prep school, in my imagination, which is to say my ignorance, was a waiting congregation of superior youth rather than the hothouse of class distinctions it would prove. Does it go without saying that I had as little sense of humor as a dog? If someone slipped and fell I thought this was funny but otherwise couldn’t find a reason to laugh.

The songs on the radio said nothing to me about my life. And as the elder brother of two sisters I had no one to induct me into the mysteries of sophisticated music for teenagers. My method was to choose a band, almost at random, from the “college” chart at the back of Rolling Stone, and to buy the band’s latest tape whenever I could get to a record store; the nearest was thirty miles away. One challenge with parents who themselves grew up on rock and roll is the difficulty in scandalizing them with your own tastes, and it’s clear to me now that the bands I selected from the college charts were those whose names suggested my parents might find their music offensive or at least bewildering. The appeal of the Smiths’ name came from the strangely arrogant declaration of commonness, and I liked the punkish implication of regicide in the title The Queen Is Dead. That went “God Save the Queen” one better, without implying, as listening to the Sex Pistols would have done, that I harbored any intention of ever having sex.

My method was a risky one. The Screaming Blue Messiahs, for instance, had a name satisfactorily suggestive of madness and violence, but I found I didn’t really like their music. With the Smiths I got lucky. The folky tastes I’d picked up from my parents allowed me to take right away to the bright acoustic texture of Johnny Marr’s arrangements, which then conveyed me into an atmosphere far removed from any ’60s-ish mood of barefoot good health and slack openheartedness. Both side-opening tracks, “The Queen Is Dead” and “Bigmouth Strikes Again,” were surging anthems of destruction, spiteful in their very rhythms; and even where the music itself was not in the least rebarbative, inflected instead by jazz or rockabilly or West African highlife playing (strains my ear identified long years before I could name them), Morrissey remained at all times an obnoxious vocalist. Most exciting, maybe, was his way of boasting of his inadequacies. When he broke into the palace on the title track and the Queen said, Yes, I know you and you cannot sing, he replied in his unpleasantest voice: That’s nothing, you should hear me play piano.

The Smiths were the first contemporary band I encountered that enabled the all-important act of identification with the singer. No one could touch Morrissey for literateness and melancholy, and if I knew anything at the time it was that I too wanted to write and was unhappy, woebegone, that is, in the trackless way of early adolescence, where I couldn’t see how I had ever come into this condition or might ever get out. And then there was the more curious fact, according to Rolling Stone, that in a literal sense no one could touch Morrissey. This witty, famous, and in my opinion handsome man was a self-proclaimed celibate with no interest in sex. His superiority was his sadness, his sadness his solitude, and his solitude his martyrdom. He was too good for this world, or at least for famously miserable Manchester, never mind the bypassed cow town of Eagle, Colorado, where every household appliance was like a new science, and all that happened in high school was the girls got pregnant and the boys got trucks.

May I admit that my headlong identification with handsome Morrissey was enabled by another circumstance? Now at thirty-five I begin to have the face I deserve, and already in high school it was clear I was not to be a tall man, but in middle school things were different. After having been a boy ignored by girls, suddenly I was fending off requests to “go” with them; and when away games and tournaments took us to other schools (I was a starting linebacker on the football team, a benchwarmer at basketball, and a very erratic wrestler), more girls petitioned me with folded notes containing phone numbers. This change was a boon, since being attractive, if you’re feckless and morose, can substitute for actual activity, and permits you, above all, to feel that your isolation from the human race owes as much to your rejecting it as to its rejecting you. In practical terms, however, I had no idea what to do with my looks besides trade them for the opportunity to get my hands on some mammary glands. And yet when I succeeded for the first time in effecting this momentous transaction I learned that tits, to the touch, were no different from regular skin, like you’d find on someone’s ankle or belly.

With male classmates, things weren’t much better, since as a boy without a sense of humor I felt ill at ease and almost foreign among them. When the friends I would soon abandon for prep school came over, I never played the Smiths; this was music for listening to alone while you lay in awe on your bedroom floor. And there would have been equally little sense in admitting that in emulation of Morrissey I’d adopted a program of celibacy—a commitment I couldn’t explain or, probably, should an opportunity present itself, uphold. In general, the phenomenon of other people was a matter of polite endurance while I waited to resume my self-contemplation. I was especially uncertain whether to class my traits as virtues or defects, and for this state of narcissistic suspension the Smiths were the perfect soundtrack. Already I must have apprehended that Morrissey’s words, for all their eloquence, possessed the supplemental eloquence of meaning the exact opposite of what they said. Because in truth he liked to be alone. He wanted to be unlovable. Which didn’t really mean he was—it just meant he didn’t want to know if he was or not. The problem with other people is that ultimately they have to decide what they think of you and how much time they’d like to spend in your company—whereas you, being stuck with yourself, are spared the necessity of such conclusions.

Before long, I had added to my Smiths collection the eponymous first album, as well as Meat Is Murder, on which my favorite track was “That Joke Isn’t Funny Anymore.” Best of all, though, was Louder than Bombs. Bought at a mall in Denver on a trip with my family, this stupendous compilation of singles and B-sides remains one of the happiest purchases of my life: twenty-four songs that I’d never even known existed! It was all but unbearable to sit in the backseat of the car reading the lyric sheet during the long drive back to Eagle—but there could be no question of asking my parents to play the tape.

Up to then they’d listened to even the worst of my music with curiosity or at least without complaint. They’d never protested the heavy metal affectations of Def Leppard or Ronnie James Dio’s forays into satanic imagery, never mind the soggy lugubriousness of Dennis DeYoung, former lead vocalist of Styx and the living low point of my prepubescent tastes. And once I graduated from the Top 40 to the college charts, they were similarly unperturbed by the fuzz and churn of Hüsker Dü or the nasal nonsense of R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe. Ruinous tolerance of the baby boomers! In fact my father helpfully explained that R.E.M. meant rapid eye movement—I know, Dad—and that Hüsker Dü was a memory game played by Norwegians. But the Smiths my parents could not abide. Morrissey’s voice on the living room stereo seemed to cause my mother genuine physical distress—The moaning, she said, in pain, the droning, the monotone—and more than once she’d insisted that I put on something, anything else. It was great: I felt credentialed as a teenager. And in this way I duplicated the Smiths’ own discovery, namely that if there is one adolescent attitude more insufferable than the punk rock sneer, it’s that combination of superiority and self-pity best expressed by Morrissey.

While beneath the abject vocals runs—most perverse of all!—a current of delight.

I liked to think of myself as miserable at the time, and can’t have been completely wrong about this. But I believe that as I plotted my escape from home and from rural idiocy, and contemplated the vocation of poetry, I was happier than I knew or could say. I was becoming someone I might enjoy knowing, for all that the ineluctable sorrow of the poetic personality would forever remain my cross to bear. And in listening to the Smiths now, as I’ve never stopped doing for long, I detect an analogy to this smuggled cargo of enjoyment—because it isn’t really, though it can seem so, that Morrissey’s miserabilist lyrics and freestyle moaning have nothing in common with Johnny Marr’s jangling, joyous music. It’s more nearly the case that the music supplies the secret truth of the words, an occult gladness at their heart.

All skill is joyful, said Yeats—and it’s worth remembering that the Smiths were not only a great band but also a very good one. Johnny Marr in particular was a guitar savant, and the band became expert around him. Born John Maher, he met Steven Morrissey for the first time at a Patti Smith show in 1979, but once the two formed a band, three years later, it was too late for punk, and anyway Marr’s fingerpicking virtuosity and magpie tastes in music caused him to scorn any three-chord cloddishness. All that remained of punk for the Smiths was a chary attitude toward guitar solos (never indulged till the final album), a DIY approach to business matters that ultimately proved their undoing, and one more musical idiom to exploit at will. It was typical of Marr to conceive of a chord progression (for “The Headmaster Ritual”) as, in his words, what Joni Mitchell “would have done had she been an MC5 fan or a punk rocker.” A similar cool lucidity, uncanny in a teenager, marked the way he recruited Morrissey: “I wanted someone who was just a singer and wasn’t playing an instrument. I didn’t want a musical cowriter. I wanted someone who looked good and was serious about words. But most of all, I wanted someone who was as serious about it as a life option as I was.”

Marr and Andy Rourke, the band’s bassist, had been in a funk outfit before the Smiths, and Rourke’s twirling “song-within-a-song” bass lines (as Marr called them), played at the high end of his instrument’s range, made for a lot of the Smiths’ distinctive sound, while the melodic work they did freed up Marr’s guitars for blooming chromatic excursions. The only real primitive in the Smiths, from a musical standpoint, was the drummer Mike Joyce, late of the Manchester punk band Victim, and after the Smiths’ initial recording sessions exposed his limitations, he set about diversifying his attack. Before long he was capable of shimmering high-hat dazzlement as well as a tom-tom fusillade or glam-rock stomp. And it seems to me that the Smiths’ music, considered apart from Morrissey’s words, often carries through from major to minor chord and back again a mood of continuous pleasure gained from the realization of one’s gifts.

The instrument-playing Smiths were all thrillingly young (Morrissey being four years their senior) when the band formed; Johnny Marr was just eighteen and would only be twenty-three when they broke up. And note something else: each of the four band members was a first-generation Englishman and the son of economic migrants from Ireland. Surely among the things you can hear the band forging in the smithy of its sound are the tools of release from the constrictions of immigrant life. “A rush and a push and the land that we stand on is ours,” sang Morrissey, adapting an old Republican slogan to the purposes of a conquest in reverse. The Smiths were in their own eyes a tremendous, historic band much deserving of popularity—Morrissey was notably obsessed with their position on the UK singles chart—and they knew they might get what they wanted.

Still, the question remains of what the bright, glad music of Johnny Marr and the rhythm section has to do with Morrissey’s ill-humored words and off-key moaning. After all, Morrissey couldn’t read music or play an instrument and often recorded his vocal only after the rest of the track was completed. And when you first listen to a song like “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now” it can seem that the Smiths are afflicted with as extreme a case of what you might call words/music dualism as anything the most riven Cartesian could suffer by way of a mind/body split, or else why should such a maundering recitation of self-pitying complaint be laid down atop a piece of music virtually simpering with felicity? I couldn’t have answered the question at age fourteen, but then I doubt I would have loved Morrissey so much at the time if I hadn’t detected at a level beyond words—the level, precisely, of music—that he too was having a good time.

The apparent paradox is that while Morrissey complains of his clumsiness and sorrow and self-doubt, the music that backs him up is deft, assured, and often simply happy. There’s irony there, of course, but the deeper and more interesting thing is identity: despondency and exultation made one. The closeness of Morrissey’s vocal lines to Marr’s and Rourke’s melodies tends to produce the impression that the words have summoned the music, rather than the other way around. Listen again to the songs, and notice how when Morrissey wonders how you can stay with a fat girl who’ll say would you like to marry me? and if you like you can buy the ring? and when he says that the story of his life is that he was once sixteen, clumsy, and shy, you can hear melancholy making a deal with happiness. The deal is off the books but unconcealed.

Melancholy, after all, can act as happiness’s enforcer. Sadness can serve as a pretext—one is often useful—for saying I can’t go out tonight (I haven’t got a stitch to wear) and I’m not the man you think I am (I’m sorrow’s native son) and, no, I’ve never had a job (because I’m too shy!). So tell the people at the threshold to your room that, alas, you must stay inside to mope. Then shut the door and rejoice: solitude is the only intimacy that’s not intrusion. Besides, alone again you can work on your lyrics about the pathos of being alone.

I arrived at St. Paul’s School in the fall of 1987. One of the few decorations I brought for my room was a Smiths poster, and the first time I left campus I went straight to the record store and purchased a copy of the just-released Strangeways, Here We Come. It would have been a happier occasion if Rolling Stone wasn’t reporting that the Smiths had split up.

My mourning of the Smiths was complicated by actually listening to Strangeways. The use of synthesizers offended my teenage puritanism and, more than that, Morrissey’s lyrics had now vaulted so far over the top that even I could detect a hint of camp. I understood that “Unhappy Birth...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- Contributors

- About the Editor

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

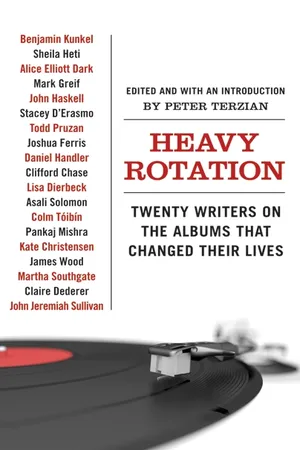

Yes, you can access Heavy Rotation by Peter Terzian in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Fashion Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.