The messages our culture gives us about the relative roles of Ego, Self, and Soul can be confusing and contradictory. Most management literature focuses on a healthy Ego, to the exclusion of both Self and Soul. Political theory tends to focus on such Ego concerns as equal access to jobs, pay, education, and status. Psychology generally emphasizes healthy Ego development, and many psychologies do nothing else.

Transpersonal psychology, as well as the better part of contemporary religion (whether Eastern or Western), develops the Soul and Spirit, but many times to the detriment of the Ego. Often this takes the form of a conscious and explicit desire to get rid of the Ego so that the individual can bow completely to God’s will. Only archetypal psychology honors all three, and sometimes even in it practical Ego concerns don’t get their proper emphasis.

There is a crying need in the contemporary world to honor Ego, Self, and Soul and to recognize the ways that the Ego should be reeducated (not eliminated) when higher order transcendent functions are developed. Indeed, it is the union of Ego and Soul that makes possible the birth of the Self. As I have studied contemporary psychology, theology, politics, management, and self-help literature, I have become more convinced that it is possible for each of us to be happy, successful, “self-actualized,” and spiritual. It is also possible to “follow our bliss” and still be a responsible citizen, parent, and friend and to live in responsible and loving community with others. The secret is to take the journey and find yourself.

The twelve heroic archetypes described in Awakening the Heroes Within help our psyches develop. The three stages of the hero’s journey—preparation, journey, return—parallel exactly the stages of human psychological development: we first develop the Ego, then encounter the Soul, and finally give birth to a unique sense of Self. The journey of the Ego teaches us how to be safe and successful in the world; the journey of the Soul helps us to become real and authentic as we encounter the deepest mysteries of life; and the journey of the Self shows us the way to find and express our authenticity, power, and freedom.

Mandalas of Ego, Soul, and Self

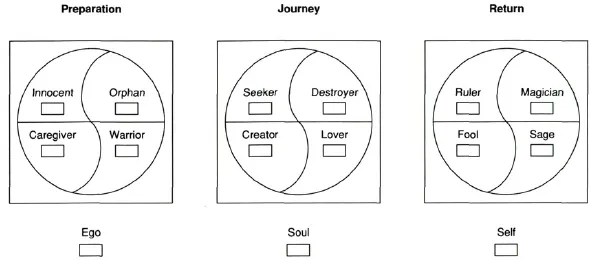

The illustrations that follow place each set of four archetypes in a mandala. According to Jung, the number 4 and the shape of the mandala are associated both with wholeness and with the discovery of the Self.

- Place your score for each archetype in the box provided below it.

- Add together your Innocent, Orphan, Warrior, and Caregiver scores to reach your aggregate Ego score. Place that number in the box provided for the heading “Ego.”

- Add together your Seeker, Destroyer, Lover, and Creator scores to reach your aggregate Soul score. Place that number in the box provided for the heading “Soul.”

- Add together your Ruler, Magician, Sage, and Fool scores to reach your aggregate Self score. Place that number in the box provided for the heading “Self.”

5. Note which of the three has the highest score. If it is the Ego, this may mean, at present, that you are proving yourself in the world or are preparing for the journey (or the next stage in it). If it is the Soul, it may indicate a time of great transition—that you are in the process of deepening and becoming more authentic and real. If it is Self, this may be a time of expressing yourself in the world, of being aware of your power and experiencing wholeness.

The Ego is the “container” for our life. The Ego creates a boundary between us and everything else and mediates our relationship with the world. It also helps us learn to fit into the world as we know it and to act to change that world to better meet our needs.

The Soul, which Jungians equate with the unconscious or the psyche itself, connects us with the transpersonal. The Soul is also the repository of all the potential of the human species, potential that lies within each one of us, like seeds germinating and ready to sprout if external conditions are propitious (analogous to enough sun, water, and fertile soil). For people who believe in an afterlife, the Soul is the part of us that lives on after the body dies. But it is not necessary to believe in an afterlife to connect with Soul or to use the concepts in this book.

The Self signifies the achievement of a sense of genuine identity. When the Self is born, we know who we are, the disjointed parts of our psyche come together, and we experience wholeness and integrity. Our task then becomes to find adequate ways to express ourselves in the world, and in so doing make the contributions we alone can make to bring joy to our own lives and help the wasteland bloom.

The first four archetypes—the Innocent, the Orphan, the Warrior, and the Caregiver—help us prepare for the journey. From these four guides, we learn to survive in the world as it is, to develop Ego strength and, beyond that, to be productive citizens and good people, with high moral character.

The second four archetypes—the Seeker, the Destroyer, the Lover, and the Creator—help us on the journey itself, as we encounter our souls and become “real.” The final four archetypes—the Ruler, the Magician, the Sage, and the Fool—mediate the return to the kingdom. In the process, they help us learn to express our true selves and transform our lives. They take us beyond heroism into freedom and joy.

The hero is often said to be the archetype of the Ego, but this is only a partial truth. The heroic journey of individuation encompasses Ego, Soul, and Self. Establishing a healthy Ego, however, is the prerequisite for taking the journey safely.

The Ego is the seat of consciousness, the recognition that there is an “I” separate from the mother and the rest of the world, an “I” that can affect that world. The mature adult Ego develops its capabilities in order to fulfill all our needs, not just the need for safety. The developed Ego helps us meet our needs not only for survival, satisfaction, safety, love, and belongingness, but also for self-esteem, self-actualization, and even transcendence. It also balances our individual needs with the needs of others, and in that way contributes to the survival and development of the individual, the family, the community, the nation, and the species.

In the beginning of life, however, the Ego is unformed. We come into this world small, fragile, and helpless. We have little or no control over our environment, only the ability to cry in pain or to inspire love and care by looking cute, vulnerable, and innocent. We are left in the care of parents or other adults who, however hard they may try, do not always guess right about what we need. As we gain some control over our movements, sounds, and actions, we begin to learn that what we do can affect what happens to us. With this awareness, Ego is born.

No matter how old, wise, or mature we become, each of us has within us a vulnerable little child who still bears the scars—whether great or few—of our formative years. The Ego’s first task is to protect that inner child. At some point during childhood, the Ego begins to take on some of the protective function from the parents, and gradually, with maturation, assumes that task completely.

The Ego’s next task, and its basic function, is to mediate our relationship with the outside world. It begins by ensuring our survival, and then concentrates on acquiring worldly success. In healthy situations, children can trust parents and other adults to look after their safety. Then they can focus on exploring the world and learning to interact effectively with it. In dysfunctional families, however, children’s Ego development may be hampered if they have to take over responsibility for survival and safety needs too early. Nonetheless, the experience of some hardship or difficulty is critical to the development of Ego strength. Whether or not the externals of our lives are difficult, the period of preparation for the journey often seems very hard—if only because we do not yet possess the skills that can make life easier.

The Ego and the Hero’s Journey

Because the challenge of the past few centuries has been the development of the Ego, the stories we identify most readily with the hero are those about Ego development. The classic hero on a white horse, the knight slaying the dragon and rescuing the damsel in distress, and the damsel in distress defending herself against the onslaughts of the would-be rapist or seducer are all versions of this classic story.

Whether the hero is a knight, cowboy, explorer, saint, or political activist, the story is essentially the same. The hero and the kingdom are in danger from some hostile force. The victim to be rescued may be inside oneself (one’s inner child or inner damsel, one’s virginity or liberty) or in the world beyond, but the key is having the courage and ability to defend the gates. The hero protects and defends the boundaries of the kingdom so that life within can flourish and grow.

The hero is often also the conqueror, the man or woman who goes after what he or she wants—new land, fame, fortune, love, liberty—and gets it. But the capacity to get what we want and protect our boundaries does not, in itself, make us heroes. Indeed, we share these qualities with great villains. What makes a hero a hero is a nobility of spirit manifested as concern and compassion for others. That is what causes heroes to rescue victims.

In the modern world, we act out this plot daily. Few of us literally slay dragons or even villains. The swords we use are less often literal weapons and more often money, status, image, power, influence, and highly developed communication skills. But the pattern remains the same.

Preparation for the journey requires each of us to be socialized adequately to be effective in the society in which we live, and then to separate from the collective view of the world enough to assert independent values, opinions, and desires. Finally, it demands that we use this capacity for autonomy and independence, not simply for selfish ends—although we do want to seek our own good—but for the good of the whole as well.

Archetypal Influences on Ego Development

The archetypes associated with Ego development—the Innocent, Orphan, Warrior, and Caregiver—help us learn to take responsibility for our lives, even when we do not yet know how to do so. Together they teach us the components of character: the trust required to learn the basic skills of living; a sense of the interdependence of human life and the ability to do our parts; the courage to fight for ourselves and others; and an identification with the greater good, which allows us to give to, and even sacrifice for, others.

These archetypes also help us establish the fundamental components of Ego consciousness. The Innocent helps us develop the persona, the mask we wear to establish our social role. The Orphan presides over the parts of our psyches we repress, deny, or simply hide so that we can establish a persona acceptable to ourselves and to others. The Warrior establishes the Ego per se, with its focus on protecting the boundaries and getting our needs met. It also acts in the service of the Superego, or Ego ideal,1 to squelch or punish tendencies it sees as unethical, self-destructive, or harmful to others. The Caregiver presides over the opening of the heart so that our goodness is motivated by genuine compassion for self or others. Together, these four archetypes help establish a container—for brevity we can call it the Ego—that can allow the Soul to flow through.

The Innocent

The Innocent helps establish the persona—the mask we wear in the world, our personality, our social role. Although this external image lacks depth and complexity, it provides us and others with a sense of who we are and what can be expected of us.

The pressure to have a persona starts early with the question, “What are you going to be when you grow up?” Adolescents may seek a primary sense of identity in popular music, current fashions, and enjoyable activities. As adults, we identify ourselves by the jobs we do and perhaps also by our life-styles. The fact is, as every Innocent knows, we must have a persona to fit into the society.

Early in life, the Innocent in each of us looks around at available options and chooses a persona. The Innocent within wants to be loved and be a part of things. It wants us to be socially acceptable, to fit in, to make others love and be proud of us. Like a child, it is not particularly critical of the group it wants to join. At best, it will choose a persona that is positive and socially adaptive. At worst, it may choose a criminal persona to fit into an environment that perceives honesty as a sign of naïveté. Whatever the choice, the reason for having a persona is always to help us have a social place or place in the family—and ideally to be admired and well liked. Unless we do, we cannot engage in the world around us.

The Orphan

Once the Innocent chooses the persona, the Orphan within, who is a survivor and a bit of a cynic, sizes up the situation and sees which of our qualities will have to be sacrificed or go underground to fulfill that new image. For example, a child who chooses a conservative life-style will have to sacrifice his flamboyancy, while one who chooses a criminal persona will have to repress her concern for others. The third child in a family might think, “My big sister is the smart one and my brother is the talented one; I’ll be the personable one”—thus repressing intelligence and talent in the interest of being fun or charming.

The Orphan is also the part of us that learns to recognize and thus avoid situations that are likely to hurt us—from the potential kidnapper, to the bully down the street, to the emotionally abusive relative. It tries to protect us from being abandoned, hurt, or victimized. To do this, it may act on knowledge the persona cannot even acknowledge having, thus becoming a secret and valuable, but hidden, sidekick.

We all have a collection of orphaned or banished selves living in the personal or collective unconscious. Many of these can be brought back into consciousness through analysis and other forms of therapy, greatly enriching the psyche. Others may remain unconscious. And some occupy a border zone. We know about them but because (perhaps rightly) we disapprove of them, we do not allow them freedom of act...