1

Travels in the Realms of Gold

The translation of [the Greek word] Anastasis as Resurrection is correct. But any designation of the subject matter of this iconography as the Descent or Harrowing of Hell misrepresents and distorts the message of the chosen label Anastasis. The title and subject matter of this image refer not to the Descent of Christ into Hell, Hades, Limbo, or Inferno, but to the raising of Christ and his raising of the dead. . . . In the image of the Anastasis, Adam stands for Everyone. . . . “Anastasis” refers simultaneously to the Resurrection of Christ, Adam, and mankind.

ANNA D. KARTSONIS, Anastasis: The Making of an Image*

WE LEAVE Orlando, Florida, the evening of Sunday, April 22, 2012, and, with plane changes at Frankfurt and Athens, arrive at Larnaca in the Greek portion of the divided island of Cyprus late the next evening. Tired to exhaustion, we are relieved to see our driver standing at the exit with “Crossan” on her upraised sign. Our weeklong home is the Forest Park Hotel in the tiny village of Pano Platres high in the Troodos Mountains. We start the four-thousand-foot climb from the coast in a 1998 white Mercedes beautifully preserved and extremely comfortable despite 150,000 miles on the odometer.

That forty-three-mile trip takes an hour and a half, giving us lots of time to become acquainted with our driver, Sharon Ioannou, an Englishwoman married to John, a Greek Cypriot, who restores and races antique cars. We tell her about our research project in the mountain villages around Platres, where small but fully frescoed churches span four hundred years, from the twelfth to the sixteenth century. Ten of them form, as UNESCO’s World Heritage report says, “one of the largest groups of churches and monasteries of the former Byzantine Empire.”

Sharon drops us at the hotel around midnight and, standing at the entrance door, we show her the daily itinerary for our visit. She agrees to be our driver for the entire week, and we stagger upstairs to bed. We soon discover that Sharon is not just a driver, but a necessary facilitator. She phones ahead each day to get visiting hours and, in several cases, finds church key holders who open the buildings for us as the only visitors. By the end of the week, Sharon and John are our friends within the ancient protocols of Mediterranean hospitality.

Each day we head out in a different direction from our Platres base with diary for details and camera for pictures. As the week progresses, Sharon notices how we focus in every church on the life-of-Christ frescoes and especially on the ones representing the Resurrection. It is, by the way, only two weeks after Easter, and neon “Kalo Pascha” signs across the main road into several of the mountain villages greet us as we enter.

One day, in the car on the way home, Sharon announces that she has a question for us. “I see your interest in researching Easter traditions,” she says, “but here is my problem with Easter. When my Mum comes over for the holidays, we always go to the Easter Vigil service in Platres. After the new fire is blessed outside, the fully robed priest goes to the closed door of the church and attempts to push it open. But the oldest man in the village stands inside and pushes against him. That seems so unfair. Why choose the oldest man in the village to withstand that much younger and stronger priest?”

Why indeed? Ten years earlier we would have shaken our heads and said that we had no idea how to explain the ceremony. But now, in response, we explain in detail why Easter’s symbolism can involve a Stronger One pushing in the door against an Older One. In the Easter Vigil this symbolizes the Risen Christ, a personification of Life, struggling successfully against Hades, personification of Death. In fact, this book is simply that moment’s explanation writ large—and with pictures! We are able to explain that Easter Vigil action to Sharon because by April 2012 we are already deeply involved in a project that began a decade earlier in the eastern Anatolian plateau, about 275 miles north of the pine-clad mountains of Cyprus.

Our fascinating historical detective story begins around 4:00 P.M. on Wednesday, September 18, 2002. The “tetrarchy” waits in the arrivals hall of Esenboğa International Airport in Turkey’s capital city of Ankara as our group clears customs. We leave immediately for the hotel, and on Thursday morning our bus heads south toward Pauline territory in Tarsus and Antioch.

Our first stop, however, is in Cappadocia, where twin volcanoes have created a landscape encrusted with volcanic tuff; where erosion has molded volcanic outcrops into spires of rock and pillars of stone; where valley sides in Göreme, Zelve, and Peristrema hide fully frescoed Byzantine churches inside their rock-cut faces. We have three days in Cappadocia, but our major focus is on Göreme’s churches from the tenth and eleventh centuries—before Byzantine Christianity lost Cappadocia and most of Anatolia to Selçuk Islam in 1071.

Figure 1.1

That afternoon, our group visits six or seven rock churches in Göreme’s open-air museum, but in two of them something sparks for us without our recognizing, at that time, that anything had happened.

The archaeological park’s circular space can hold lots of visitors, but narrow stairs, entrances, and interiors cause bottlenecks before each of those rock-cut chapels. We have to wait outside, for example, to enter the Dark Church, or Karanlik Kilise, a magnificent miniature Byzantine cathedral from around 1050.

The church’s design is a cross inside a square. Frescoes cover its columns, vaults, and domes. Those images, protected by centuries of darkness—hence the name—are completely restored and are now the best preserved in all of Cappadocia (Fig. 1.1; note the Anastasis, or Universal Resurrection, at the extreme right).

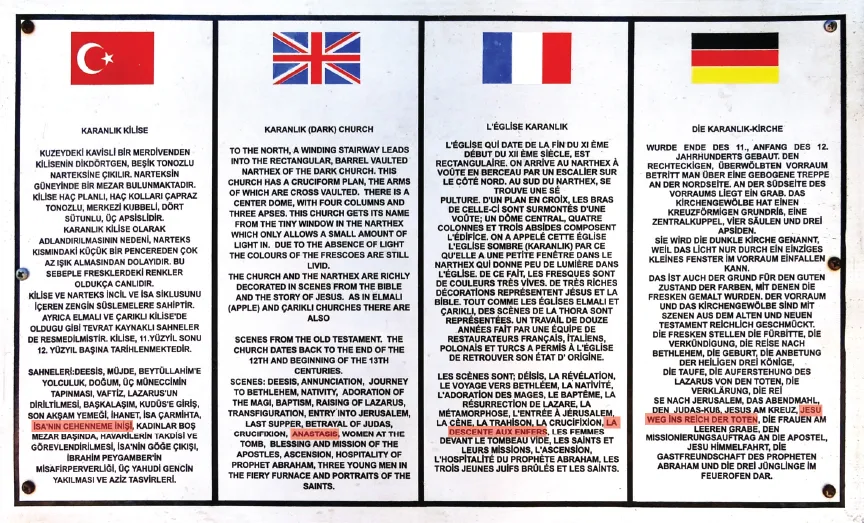

As we wait our turn to enter the church—more or less patiently—we read the explanatory sign given in Turkish, English, French, and German (Fig. 1.2, red-color emphasis added). The English version records the fifteen scenes of the life-of-Christ frescoes inside: “Annunciation, Journey to Bethlehem, Nativity, Adoration of the Magi, Baptism, Raising of Lazarus, Transfiguration, Entry into Jerusalem, Last Supper, Betrayal of Judas, Crucifixion, Anastasis, Women at the Tomb, Blessing and Mission of the Apostles, Ascension.”

We notice that in the English section the Resurrection is called the Anastasis. Ana-stasis is a Greek word that literally means “up-rising.” “Interesting,” we think. “The Resurrection as an uprising . . . but by whom and with whom, for what and against what?”

Still waiting, we look at how the other three languages name the inside fresco called the Anastasis in English. In Turkish it is “Jesus’s Descent to Gehenna,” in French, “The Descent to Hell,” and in German, “Jesus’s Travel to the Kingdom of the Dead.” We discuss two questions there and then—but vaguely and fleetingly, in idleness, as we await entrance into this glorious church in a cave.

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.3

First, why use the Greek term “Anastasis” rather than the English word “Resurrection” in an otherwise English-language sign? Second, since Anastasis/Resurrection is about ascending upward, why do the other three languages describe a descending downward? Still, although those questions come up there, they are just idle curiosity at this stage.

Once inside, facing forward under the central minidome, we find the expected series of frescoes showing the Annunciation to the Ascension in a glorious swirl all around us. They are not depicted as a continuous narrative series, however, but as individual celebrations, as monumental icons of the great annual feast days. Life-of-Christ history appears here as life-of-Christ liturgy—and we are standing inside it.

In the right side aisle is an easily recognizable Crucifixion scene, but immediately to its left is another one recognizable to us not by its content, but only by its name. It says HANACTACIC, in capital Greek letters, and that is where the outside sign got “Anastasis” as its word for “Resurrection” (Fig. 1.3). Yet it does not look like any Resurrection scene we have ever seen.

The central and tallest figure in the painting is “Jesus Christ,” identified by his cruciform halo, his name in the traditional two-letter Greek abbreviations IC XC, and a long ceremonial cross in his left hand. He strides forcefully to viewer right, but looks backward as his right hand firmly grasps the right wrist of a white-haired, white-bearded man identified in Greek as “Adam.” Behind Adam is a woman identified as “Eve,” and both are being pulled from their sepulchers. Behind them the barest tops of six other heads are visible, identified as “Prophets.”

To viewer right are two figures, both crowned, one older and bearded, the other younger and beardless. They are identified as “David” and his son “Solomon.” Behind them are two unidentified top-of-heads-only individuals. All of the figures on both sides of Christ have halos. What appears beneath Christ, however, is the most striking element in the entire fresco.

Christ is emerging from a dark semicircular area below the ground (note the trees above the dark area), and he is standing atop, or trampling down, a full-bearded prostrate figure whose feet and hands are chained. This figure looks up with frightened eyes at Christ, whose long cross seems to hold his head down. What is striking is that the image is not of Satan, the opponent of God, but of Hades, the custodian of the dead. He lacks both halo and name, but he is most certainly Hades, the gatekeeper and personification of the “Kingdom of the Dead,” as we read in German on the sign outside. Beside Hades are scattered locks, bolts, and bars from a pair of narrow doors, flatten...