CHAPTER

1

THE COLOR OF COMPROMISE

Four young girls busily prepared for their big day. It was September 15, 1963, the day of the “Youth Day” Sunday service at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, and the girls, along with the other young people of the congregation, would spend the next few hours singing songs, reciting poems, praying, and giving encouraging messages in front of hundreds of beaming parents. The girls—Addie Mae Collins (14), Denise McNair (11), Carole Robertson (14), and Cynthia Wesley (14)—had just finished Sunday school and were in the church basement making final adjustments to their white dresses when the bomb exploded.1 The blast, which killed all four girls and injured at least twenty others, left a hole in the floor five feet wide and two feet deep. It decapitated Cynthia. Her parents could only identify her body by her feet and by the ring she was wearing.2 A newspaper report at the time indicated that all of the church’s stained-glass windows had been destroyed except one. That window depicted “Christ leading a group of little children. The face of Christ was blown out.”3

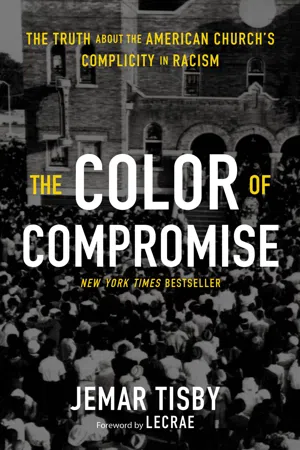

Three days later, an integrated crowd of thousands of mourners gathered at Sixth Avenue Baptist Church for a funeral for three of the girls. So many attended that the mass of people spilled out of the sanctuary and into the street.4 The cover of this book shows the scene of the funeral.

Before the funeral, on the day after the bombing, a young, white lawyer named Charles Morgan Jr. delivered a lunchtime speech at Birmingham’s all-white Young Men’s Business Club. Of course, he had heard about the tragedy in his city, and this lifelong southerner jotted down some words about racism and complicity that would prove to be a turning point in his life.

Reflecting on the events he said, “ ‘Who did it? Who threw that bomb? Was it a Negro or a white?’ The answer should be, ‘We all did it.’ Every last one of us is condemned for that crime and the bombing before it and a decade ago. We all did it.”5

Morgan recognized that no matter who had physically planted the dynamite, all the city’s white residents were complicit in allowing an environment of hatred and racism to persist. The acts that reinforced racism happened in countless common ways. Morgan explained, “The ‘who’ is every little individual who talks about the ‘niggers’ and spreads the seeds of his hate to his neighbor and his son. The jokester, the crude oaf whose racial jokes rock the party with laughter.”6

Morgan also recognized that Christians bore as much responsibility as anyone for the state of race relations in city. “It is all the Christians and all their ministers who spoke too late in anguished cries against violence.” He then asked a series of rhetorical questions for his listeners to ponder. “Did those ministers visit the families of the Negroes in their hour of travail? Did many of them go to the homes of their brothers and express their regrets in person or pray with the crying relatives? Do they admit Negroes into their ranks at the church?”7

Some white Birmingham residents did not receive Charles Morgan Jr.’s speech well. Though many hurled death threats at Morgan personally, the threat that most disturbed him listed every place his wife and son had been on a recent Saturday. Morgan soon closed his law practice and moved elsewhere to engage in a long career of civil rights law.8

Although many people from Birmingham and beyond expressed outrage at the murder of these four black girls at church, Morgan’s point stands out—the most egregious acts of racism, like a church bombing, occur within a context of compromise. The failure of many Christians in the South and across the nation to decisively oppose the racism in their families, communities, and even in their own churches provided fertile soil for the seeds of hatred to grow. The refusal to act in the midst of injustice is itself an act of injustice. Indifference to oppression perpetuates oppression.

History and Scripture teaches us that there can be no reconciliation without repentance. There can be no repentance without confession. And there can be no confession without truth. The Color of Compromise is about telling the truth so that reconciliation—robust, consistent, honest reconciliation—might occur across racial lines. Yet all too often, Christians, and Americans in general, try to circumvent the truth-telling process in their haste to arrive at reconciliation. This book tells the truth about racism in the American church in order to facilitate authentic human solidarity.

In this book you’ll read about the American church’s sickening record of supporting racism. Many would prefer this history to remain locked away and hidden. But Martin Luther King Jr. gave an important rationale for shining a light on injustice, despite the pain it may provoke. “Like a boil that can never be cured so long as it is covered up but must be opened with all its ugliness to the natural medicines of air and light,” he wrote, “injustice must be exposed, with all the tension its exposure creates, to the light of human conscience and the air of national opinion before it can be cured.”9 King’s words apply to racism in the church. The festering wound of racism in the American church must be exposed to the oxygen of truth in order to be healed.

Although activists have achieved a remarkable amount of racial progress at great cost, racism continues to plague the church. One of the reasons churches can’t shake the shackles of segregation is that few have undertaken the regimen of aggressive treatment the malady requires. It seems like most Christians in America don’t know how bad racism really is, so they don’t respond with the necessary urgency. Even when Christians realize the need for change, they often shrink back from the sacrifices that transformation entails.

This book is about revealing racism. It pulls back the curtain on the ways American Christians have collaborated with racism for centuries. By seeing the roots of racism in this country, may the church be moved to immediate and resolute antiracist action.

CHRISTIAN COMPLICITY WITH RACISM

While many Christian traditions and other religions have varied and valuable narratives, Protestants, especially evangelicals, have written some of the most well-known narratives of racism in the United States. Other religious groups, such as white Catholics, have certainly contributed to racism, but the narrative that unfolds in the following pages focuses on Protestant churches. Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians all have a central, sometimes repressive, place in the story of race in America. No matter which faith tradition or denomination is at the forefront of discussion, racism extends across sectarian lines.

What do we mean when we talk about racism? Beverly Daniel Tatum provides a shorthand definition: racism is a system of oppression based on race.10 Notice Tatum’s emphasis on systemic oppression. Racism can operate through impersonal systems and not simply through the malicious words and actions of individuals. Another definition explains racism as prejudice plus power. It is not only personal bigotry toward someone of a different race that constitutes racism; rather, racism includes the imposition of bigoted ideas on groups of people.

In light of these definitions, it is accurate to say that many white people have been complicit with racism. Although there have been notable exceptions, and racial progress in this country could not have happened without allies across the color line, white people have historically had the power to construct a social caste system based on skin color, a system that placed people of African descent at the bottom. White men and women have used tools like money, politics, and terrorism to consolidate their power and protect their comfort at the expense of black people. Christians participated in this system of white supremacy—a concept that identifies white people and white culture as normal and superior—even if they claim people of color as their brothers and sisters in Christ.

White complicity with racism isn’t a matter of melanin, it’s a matter of power. Other nations have different dynamics. Whether society is stratified according to class, gender, religion, or tribe, communities tend to put power in the hands of a few to the detriment of many. In the United States, power runs along color lines, and white people have the most influence.

Historically speaking, when faced with the choice between racism and equality, the American church has tended to practice a complicit Christianity rather than a courageous Christianity. They chose comfort over constructive conflict and in so doing created and maintained a status quo of injustice.

Given the history, complicity is a weak word for describing how American Christianity has often interacted with race. As historian Carolyn DuPont describes it, “Not only did white Christians fail to fight for black equality, they often labored mightily against it.”11 Complicity connotes a degree of passivity—as if Christianity were merely a boat languidly floating down the river of racism. In reality, white Christians have often been the current, whipping racism into waves of conflict that rock and divide the people of God. Even if only a small portion of Christians committed the most notorious acts of racism, many more white Christians can be described as complicit in creating and sustaining a racist society.

WHAT A HISTORICAL SURVEY IS AND ISN’T

Before jumping into the waters of history, it’s important to acknowledge the limitations of a book like this one. Every book is an introduction, an invitation to further study. This is especially true with a historical survey.12 A survey covers a large amount of historical territory quickly. It gives readers a sense of the historical patterns and how they have changed or persisted over time. Yet surveying the history of the American church and racism leaves no doubt that race has exerted an undeniable influence on the way Christianity has developed in this nation.

At the same time, a survey focuses on breadth instead of depth. A high degree of selectivity goes into a historical survey, and more gets left out than put in. So it should come as no surprise that important leaders, events, and stories may not even get mentioned in this book. This is not to say that the facts left out are unimportant; it is merely an indication of what can be accomplished in a single volume. This book is a doorway into the endless hallways and chambers of American history and makes no claim to be a comprehensive treatment of race and the American church.

The Color of Compromise focuses on prominent figures, precipitous events, and well-known turning points in American history. These stories serve as an entry point to a deeper study of the host of local people and lesser-known narratives with significant historical and social importance. But even though most of history’s precipitous events hinge on the actions of numerous people at the grassroots level, certain individuals and their actions symbolize broader movements and sentiments. Widely recognized people, such as George Whitefield and Billy Graham, are highlighted not because their voices matter most but because their stances represent larger cultural trends.13

This book focuses on the black-white racial divide in American Christianity. Of course, there are many other intractable conflicts along racial and ethnic lines. These various schisms have their own unique stories and dynamics. It would be impossible to do them all justice in a single volume. Yet justice for one group can open pathways for equality to other groups.14 The principles outlined in this book, when applied to other racial and ethnic conflicts, can help lead to greater understanding and positive change.

Even though a survey approach poses several limitations, it also offers the opportunity to see long-term trends and change over time. Throughout this journey several themes dot the horizon of history. One notable theme is that white supremacy in the nation and the church was not inevitable. Things could have been different. At several points in American history—the colonial era, Reconstruction, the demise of Jim Crow—Christians could have confronted racism instead of compromising. Although the missed opportunities are heartbreaking, the fact that people can choose is also empowering. Christians deliberately chose complicity with racism in the past, but the choice to confront racism remains a possibility today.

Another theme this survey reveals is that racism changes over time. Skin color is simply a physical trait. It is a feature that has no bearing on one’s intrinsic dignity. As the following chapters show, people invented racial categories. Race and racism are social constructs. As society changes, so does racism. Racist attitudes produced different actions in 1619 than they did in 1919 or 2020. The malleability and impermanence of racial categories help explain how the American church’s compromise with racism has become subtler over time. History demonstrates that racism never goes away; it just adapts.

WHY WRITE ABOUT RACISM AND RELIGION?

Martin Luther King Jr. said, “There can be no deep disappointment where there is not deep love.”15 This study is not about discrediting the church or Christians. I love the church. My concern for the church and for the well-being of its people motivates my exploration of Christian complicity in racism. The goal is to build up the body of Christ by “speaking the truth in love,” even if that truth comes at the price of pain.

The church has not always and uniformly been complicit with racism. The same Bible that racists misused to support slavery and segregation is the one abolitionists and civil rights activists rightly used to animate their resistance. Whenever there has been racial injustice, there have been Christians who fought against it in the name of Jesus Christ. Christianity has an inspiring history of working for racial equity and the dignity of all people, a history that should never be overlooked.

The black church, in particular, has always been a bulwark against bigotry. Forged in the fires of racial prejudice, the black church emerged as the ark of safety for people of African descent. Preachers and leaders in the church saw the truth of the gospel message even as slaveholders and white supremacists distorted the message to make more obedient slaves. Black churches looked to the exodus of the Hebrews from Egypt as a model for their own exodus from American slavery. Black Christians saw in Scripture a God who “sits high and looks low”—one who saw their oppression and was outraged by it. Through the centuries, black people have become the most religious demographic in the United States. For instance, 83 percent of black people say they “believe in God with absolute certainty” compared to 59 percent of Hispanics and 61 percent of whites. Additionally, 75 percent of blacks say “religion is very important” to them compared to 59 percent of Hispanics and 49 percent of whites.16 Through their religious heritage, black people have passed on a tradition of struggle, liberation, and rejoicing to every generation. Black Christians have played a vital role in shaping the history of America, and they have much to share with the church universal.

But the examples given in this book do not present a positive picture. The focus is mainly on racist acts and actors. This emphasis is purposeful. American Christians have never had trouble celebrating their victories, but honestly recognizing their failures and inconsistencies, especially when it comes to racism, remains an issue. All too often, Christians name a few individuals who stood aga...