- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Section Two:

The Siren Call of the Transaction

Seven

Department Stores and How They Blew It

Now it is Cheryl’s turn. Her eyes are as heavy as Hal has commanded: She is in that hypnosis state where day recedes and yesterday or ten years ago looms large.

“My husband and I go every year to Las Vegas. It’s part of his job,” she says, mumbling a bit.

“Speak louder,” Hal suggests. “I need to hear you.”

She dutifully repeats, much more clearly this time. “My husband and I go to Las Vegas every year. It’s part of his job.”

“And why does this trip make you think about shopping?” Hal asks.

“Because there’s always a very important, very glamorous cocktail party each year,” she says, as if this were self-evident.

“Where’s the shopping?” Hal asks evenly.

“For the dress. I need a great dress each year, something new and wonderful. It’s so important to him that I look great. This past year was so, so difficult. Finding the dress.”

“Tell me about that,” Hal says.

“I went everywhere. I went to Prada and Gucci and just everywhere. All the boutiques. I went to a dress shop that I’ve always been able to rely on. Nothing.”

“What happened?” he says, like a caring physician might coax symptoms from a shy patient.

“I was talking to my mother,” she says. “On the telephone. I was worried. It was getting close to the date and I had nothing and I’d exhausted all my usual places to find this perfect dress. It was important and I was worried. She said, ‘Have you tried Macy’s?’ And I laughed and said, ‘Macy’s!’”

“Why?” Hal plays the innocent. “Why is Macy’s such an outlandish suggestion?”

“Because it’s all about those sales,” she tells him. “All those ads with the coupons and they sell housewares and furniture! How could they have my dress?”

“So what did you do?” he asks.

“I was desperate,” she tells him. “I said, ‘Mom, you have to come with me. I can’t go through all that alone.’”

“And she came with you?”

“Yes. We went right up to better dresses and I was shocked. They had lovely dressing rooms, carpeted, with those three mirrors that let you see every side of you,” she tells him. “Once the saleslady understood what I was looking for, she told us just to sit in the room and she’d bring us the dresses. My mother and I sat there and we talked and evaluated each dress. There were major designer names. And the saleslady understood, she really did, she got it, what I was looking for.”

“Did she find it for you?” Hal asks.

“Yes! She did. It was perfect!” Cheryl seems to positively beam from the memory. “It was Anna Sui! Who would have ever thought that Anna Sui would be at Macy’s! There was a great Calvin Klein too. It was almost hard to choose. I was so happy. And I needed shoes, stockings, a new bag: All of it. And the saleslady told me just to sit there and she’d go around the floor and even to other parts of the store and get the perfect things. She brought us tea in china cups and we sat there and sure enough, she had the eye! She brought four or so bags and just a couple of pairs of shoes, but each one was spot-on. I just had to choose which one I felt was more me.”

“That sounds wonderful,” admits Hal. He seems ready to move on. The other women in the room seem envious, almost. Feet are shuffling. Heads are shaking.

“It was,” Cheryl says. “Right up until the end.”

“What happened?” Hal asks, shocked.

“When it was time to pay for it, I gave her my charge card and I was getting dressed,” Cheryl tells him. “And she brought the bill for me to sign into the dressing room. It was for much less than what I’d thought. Much, much less. She told me everything was 40 percent off that day, and she didn’t think I was the kind of shopper who had a coupon, so she’d gone ahead and clipped one for me from the circular.”

“How did that make you feel?” says Hal, like a good shrink.

“Cheap. I didn’t want it to be cheap. I didn’t want her to have clipped a coupon for me and I didn’t like it. I thought, ‘She’s cheated herself out of part of her commission to do this,’ and then I thought, ‘maybe she thought I couldn’t afford it.’ I didn’t like this part at all. I bought everything, but it changed how I felt about the dress.”

“Did it change how you feel about Macy’s?” asks Hal.

“Wait! Wait!” she says, laughing a bit. “I just remembered. And then, and then, she asks me if I want to get a Macy’s card. I could get another percentage off on all this stuff.” The other women laugh, too, nodding.

“So, how do you feel about Macy’s?” asks Hal.

“Pretty much the way I did before,” she says with a sigh. “It’s for sales. I guess I’d go back if I were desperate enough, but it just kind of ruined it for me.”

Voilà! The Un-Shopportunity!: Macy’s gave up hundreds of dollars in this one sale. If the saleslady was on commission, she gave up quite a bit too, along with a smidgen of personal ethics: Cheryl did not have the requisite coupon, but the saleslady pretended she did. And what did they get in return? A slightly miffed customer in a denigrated piece of nearly fabulous Anna Sui at a, therefore, compromised cocktail party.

This experience was poised to become a great Shopportunity! Cheryl came to it with great anticipation, of course. The pursuit had been going on for a month before she and her mother ever entered the Macy’s dressing room. The search for the perfect dress had a great deal of prominence attached. And certainly, the dress had the potential of appreciating over time.

Macy’s, in the guise of its wise guide, the saleslady, seemed ready to deliver on the experience that a really great department store seems nearly uniquely well-equipped to handle. It was very nearly a wedding gown moment. Everything Cheryl needed was there under one roof, swirling around her with the saleswoman bringing it to ground. Had she wanted, Cheryl could have had a makeover at the cosmetics counter, been presented with an impressive array of new and antique necklaces or perhaps a new watch to further enhance her emerging look—and bought an espresso machine on a pure whim. It is all there.

Instead, Macy’s attempted to beat Wal*Mart at its everyday low price game. There are so many Shopportunities! to be had under this one roof, and yet, and yet, again and again the default setting is price. Shop with me, the store begs us and tries, essentially, to bribe us. It would not have to do this. It could triumph easily over Wal*Mart and its ilk in so many dimensions that it is just sad to watch this “giving away the store” by the store.

This is not just an apocryphal tale or isolated instance. And it is certainly not just Macy’s. It happened to me not a month later. My daughter and I were in Florida visiting my mother, who was recuperating from a serious illness. She was at last home and at last ready to care about what she was wearing. She wanted a certain kind of housedress that either buttoned or zipped up the front.

Mattie and I went to the Belk’s in a nearby shopping center. The department store setting seemed far less confusing than to try to negotiate through all the specialty retailers. I couldn’t quite see taking my five-year-old into a Victoria’s Secret to figure out if they carried anything remotely appropriate for my mother after all. The moment was emotional for us: HappySad, as Mattie says. Happy that Grammy is beginning to care about her appearance and we can do something to help. Sad that it’s been such a long, hard road back for her. Both my daughter and I wanted to get Grammy exactly the dresses she wanted and lots of them.

We found the housedresses, in her size, in the muted patterns and prints she would like, with zips or buttons right where she wanted them. We picked out five. We were pleased with ourselves, I have to say, congratulating each other on the wisdom and taste of our selections.

Then, the saleslady told us that everything that day was 30 percent off. Well, okay. Let’s pause the replay here. Why, you may ask, is this so terrible? Well, because it was so unnecessary. Belk’s gained nothing from the 30 percent it gave me.

The saleslady’s name was Linda. She was a part-time worker with no allegiance to Belk’s, which hires her for just enough hours to help Belk’s, but not enough to require benefits be paid her. She volunteered that she was living the cash-strapped life of a retiree whose pension and Social Security aren’t going as far as planned. Her husband was working part time at the nearby Ace Hardware. She was charmed by my daughter. She wanted to do something nice for us, but lacked the skill set to provide a real service. At exactly this moment, she might have said, “Some of these are zipped up the front and some are buttoned. Would you prefer having all zips or all buttons? We have an even larger selection over here,” and waltzed us over to a section we missed. But no.

Instead she asked me what I thought was an odd question, “Would you like to give one dollar to breast cancer research today?” But, hey! Okay. That’s a way of giving back some of the 30 percent she just gave me, right? So I said yes, of course. Then she beamed at me and said, “That’s great, because now I can give you an extra 15 percent off on all your purchases.”

Just why or how that happened was inscrutable to me. There seemed to be some sort of weird promotion going on, but I had the feeling that if I asked too many questions, they’d end up paying me to take the stuff home to my mother. It was bizarre. And then, of course, came the question, “Would you like to open a Belk’s charge account? There’s another 15 percent off of all your purchases.”

We were now at 45 percent off and she was offering me another 15 percent. And again, needlessly so. How will they ever stay in business? I refused, of course, feeling obligated to explain that we didn’t live near a Belk’s, not that I was worried for the future of retailing. I would have happily bought the housedresses for my mother at full price. Indeed, when I took them to the saleslady I thought I was buying them at the price listed. I would have given to breast cancer research too. What is going on?

Department stores were a 19th-century innovation, most probably introduced by Au Bon Marché in Paris. They offered everything from “swaddling clothes to grave cloths” by one account. They offered standard pricing, everything marked clearly and nonnegotiable. They offered service and a willingness to let the customer wander around the store without requiring them to buy anything. This is a prime distinction. It is fair to say that department stores invented modern shopping. Patrons entered these magnificent stores with questions, not answers. They came to discover, not to place orders.

A general store, such as the one Katherine relied upon, offered wet goods (rum and such) and dry goods (cloth, sewing and knitting paraphernalia, and other essentials of the homesteader life). The proprietor would have taken her list from her when she entered, assembled the goods, added the cost to her account and either handed them to her or delivered them. She was not expected to enter unless she wanted to buy. Department stores taught her to shop, to dream, to wonder as she wandered through. The salespeople needed to be more than order takers, they needed to provide knowledge, advice, guidance, even wisdom.

That does seem to be a compelling promise: fair pricing, radical choice, professional service. The pricing piece has always been an element of department store economics. The general store took a chance with every farmer to whom it granted an account. The shopkeeper held the account in the “Receivable” category until the farmer got the cash each harvest to settle his tab. So it priced all its products at a steep margin in order to amortize the cost of bad debt.

Department stores, on the other hand, were “cash and carry” (or at least cash and delivery). They were able to pay their vendors quickly. And they were buying in much larger quantities. Thus they routinely received discounts, which were not passed along to the shopper, but which, in fact, constituted the bulk of their profit margins.

These massive, legendary department stores grew up in this country after the Civil War because of five cultural factors. First, the urbanization of the country, resulting in hundreds of thousands of potential customers within a few square miles. Second, the increasing affluence of the industrializing population. Third, the development of mass production techniques to create the affordable goods. Fourth, the revolution in infrastructure, including the architectural, building material and public transportation that allowed for “skyscraper stores,” as well as the electricity that enabled late store hours, elevators and escalators. And, fifth, of course, an affordable, reliable, trainable workforce: women willing to work outside the home.

These were female arenas, to be sure. Edward Filene, who founded the Boston department store, called it “an Adamless Eden.” One writer described the typical store of 1910 keenly. “Buying and selling, serving and being served—women. On every floor, in every aisle, at every counter, women. Behind most of the counters on every floor—women. At every cashier’s desk, at the wrappers’ desks, running back and forth with parcels and change, short-skirted women. Filling the aisles, passing and repassing, a constantly arriving and departing throng of shoppers, women. Simply a moving, seeking, hurrying mass of femininity, in the midst of which the occasional man shopper, man clerk and man supervisor, looks lost and out of place.”

These saleswomen provided a challenge to the famous merchants of the day: Macy’s, Wannamaker, Marshall Field. The women willing to be, in the English term, “shopgirls,” were often one or two rungs lower in the economic and social pecking order of the day than the women they were to advise. An upper-class woman torn between two types of gloves, or hat, or frock for an occasion needed to respect the lower-class woman who was counseling her.

On the one hand, that meant training these women to become trusted and knowledgeable advocates for the store’s wares. They gained intense preparation, deep but not necessarily broad: A millinery saleswoman would know every manner of nuance about the meaning of ornamentation on the hats, the various methods of affixing them to the head, when and where they were absolutely required, the latest in styles from Paris, without necessarily knowing much about skirt lengths or purses. They were expert in what they sold—and they knew what they didn’t know. They knew how to pass the patron on to the next department.

Overall, their role was beyond mere servitude. They were to seek and find the very best solutions to wants and needs that might have been as remote as, well, the purchase of a Porsche 911 is from the mechanic who maintains it. Yes, of course, they were to nod willingly and dispatch a horse and carriage to deliver home the spool of thread the customer wanted, but could not bear to carry. But they were also to gently, firmly persuade the less than knowledgeable customer to select the dress, the curtains, the armoire, the jewelry, the shawl, the slippers, the private necessities appropriate to her station, if not what she thought she wanted at the moment.

On the other hand, it meant paying the salesladies, as they began to prefer to be called, a living wage and, in some cases such as Macy’s, providing them affordable housing via company-owned dormitories. It meant, as well, promoting them within the ranks of an organization. It required the creation of a class of professionals, at once credible, authoritative and personable.

Oh, what it must have felt like to walk into one of these grand buildings. Your shoulders lower. Your heart races. Whatever you need is in here and seasoned staff will help you find it. As early as 1870 one visitor totaled up the virtual army it takes to do this right: One general superintendent; 19 assistants, each the head of a department; nine cashiers; 25 bookkeepers to track the day’s sales; 30 ushers guiding shoppers to the appropriate department; 200 cash boys run...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Introduction What Becomes an Abandoned Superstore Most?

- I. New & Improved!

- II. The Siren Call of the Transaction

- III. Summary

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- Sources

- Searchable Terms

- About the Author

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

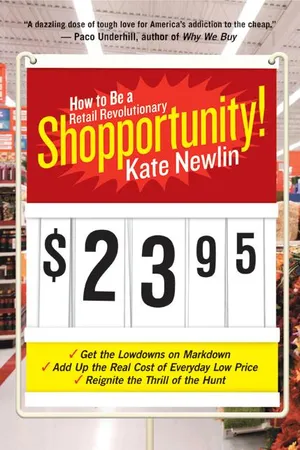

Yes, you can access Shopportunity! by Kate Newlin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Automobile Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.