eBook - ePub

Kissing the Mask

William T. Vollmann

This is a test

Share book

- 528 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Kissing the Mask

William T. Vollmann

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

"Intrepid journalist and novelist William T. Vollman's colossal body of work stands unsurpassed for its range, moral imperative, and artistry."

— Booklist

William T. Vollmann, the National Book Award–winning author of Europe Central, offers a charming, evocative, and piercing examination of the ancient Japanese tradition of Noh theatre and the keys it holds to our modern understanding of beauty. Kissing the Mask is the first major book on Noh by an American writer since the 1916 publication the classic study Pisan Cantos and the Noh by Ezra Pound. But Kissing the Mask is pure Vollman—illustrated with photos by the author with provocative related side-discussions on femininity, transgender, kabuki, pornography, geishas, and more.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Kissing the Mask an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Kissing the Mask by William T. Vollmann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatur & Literaturkritik im Drama. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

LiteraturSubtopic

Literaturkritik im Drama

Part I

BLACK HAIR

Chapter 1

“The Mask Is Most Important Always”

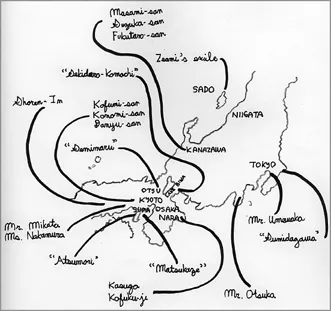

The Noh Performances of Umewaka Rokuro

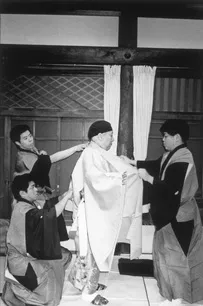

And now, on the grounds of Yasukuni Shrine, the last few cherry blossoms shiver, as do the spectators, in this April evening’s drizzly wind; and the kyogen skit about two servants who guzzle up their master’s sake proceeds loudly, coarsely beneath the Noh stage’s pagoda roof between the twin fires lit by Tokyo dignitaries an hour before, at the beginning of the entertainment; these wiggling jellies of light are, being theatrical adornments — a category which includes all earthly things — more show than substance; and I suspect that without the aid of the electric stagelights glaring in from either side of the courtyard, that painted pine on the Noh stage’s mirror-board would remain no more than a faint and complex clot of darkness. The long stage-bridge glistens, potential and void; at its far end, the rainbow curtain twitches in the breeze, like the skirt of an impatient woman; and beyond this semipermeable membrane — one of ever so many between “art” and “life” — in the mirror room, whose tatami mats feel warmly springy under one’s stockinged feet, two apprentices in blue-and-black kimonos are slowly enwrapping Mr. Umewaka Rokuro in his various shrouds. So it must have been for the preceding fifty-five generations of the Umewaka family;1 for there was an Umewaka dance troupe four centuries and more before Noh began. How did those ancientest actors prepare themselves? What masks did they wear, if any? I imagine each one taking his own silent interval, to dream upon his impending change. Thus a thousand years, fifty-five generations; this pleasant, broadfaced man marks the fifty-sixth. He is one of the most celebrated Noh actors in Japan, and has been called the best. His masked likeness appears on the cover of many a book; he performs about once a week, in Japan and out; in his spare time he sometimes reads mystery novels. The Noh corpus presently consists of about two hundred and forty plays. Mr. Umewaka keeps a hundred in his head. Standing in the doorway of this room, I can see that trembling rainbow curtain which will come to symbolize so much to me. To the right of it, a paper-windowed lattice glows in stagelight, overhanging a wall of long, horizontal slats between which the shouting actors flicker (kyogen is traditionally performed between Noh plays, for comic relief). But within the mirror room itself one gets no view of anything. This place is, as dressing rooms should be, womb and burial chamber, where an actor’s day-to-day self gets ceremented away until the resurrection two hours hence; and another self, stranger, narrower, purer, unhurriedly germinates, preparing to come out at the appointed time, the end of the kyogen.

The apprentice who works on Mr. Umewaka from the front, kneeling at his feet, is the highest-ranking, most experienced of his kind — if he is an apprentice; for he might just as likely be a koken, a watcher-from-behind, the one who glides up to the actor as needed on stage to gather up a fallen prop or straighten his kimono.2 He may be a prestigious actor who could continue the performance should Mr. Umewaka be incapacitated. In any event, one begins as an apprentice, and one commences the apprenticeship by learning which items to present at the appropriate instant; even this, like every other aspect of Noh, is said to be difficult. Mr. Umewaka stands erect and still, gazing straight ahead into the mirror. He has entered that objectified chrysalis when one can no longer live at will, nor yet give oneself over to the expression of art. What I see is not so much a person submitting to his helpers as a force consideredly drawing in upon itself, limiting, focusing, gathering, brooding. From his kimono the helpers snip gold threads unraveled by ancientness; this costume, like so many others, dates back to the Edo period (1600–1868).3 The weaving of the old kimonos is finer than today’s, not only visually but also structurally; in them Mr. Umewaka can move more freely, or I should say less constrictedly, thanks to some peculiar fashioning of the sleeves which would now cost millions of yen to reproduce. Moreover, he tells me, the artificial fertilizer ingested by the plants on which twenty-first-century silkworms feed weakens the silk. He laments: “Now they last only a hundred and fifty years — half as long as the old ones.” Accordingly, these Edo kimonos are prized by Noh actors, and never, ever washed. They stink. The assistant at Mr. Umewaka’s back has already presented a yellow-beige kimono which will frame the inner golden one; the lead apprentice kneels at Mr. Umewaka’s feet once more, and the room roars with the faint rustling of cloth. Mr. Umewaka’s face is so calm and old. I dare not say a word to him; I must not hinder his exit from this world. Now over the black skullcap goes the black horsehair wig, whose long tresses so cleanly glisten. But first they remove the yellow-beige kimono in honor of a green one; Mr. Umewaka is concerned that yellow-beige might express too great a contrast with his new black hair. Although the fourteenth-century Noh troupes which always performed together no longer exist, Mr. Umewaka frequently performs with the same persons. Moreover, he has long since mastered his particular part, whose gestures remain unalterable. Hence he forgoes Noh’s customary day-before rehearsals. Whether he first puts his right or left foot forward, this too has been predetermined for each play — but in some respects Noh resembles a musical “jam” session, requiring certain nearly spontaneous decisions (for instance, in “Kinuta” the lead role of the ageing, perishing, abandoned wife will be played by Mr. Umewaka, who must take care not to be upstaged by the younger mask and costume of the actor who plays the ambiguously seductive maidservant) — and, since, moreover, venues vary so vastly, particularly in the quality of their stagelight, Mr. Umewaka always keeps several kimonos and wigs on hand for each part, so that he can choose and alter his beauty’s skin up to the last moment. The helpers fluff out his hair as he looks into the mirror. Then they bring him a low stool, his wig coming off again as he silently sits. “At that point I don’t think about what to do anymore,” he told me later. “Up to the point where I’m dressing, I may still be planning. But at the mirror, well, I cannot be completely nothing, or at least I can think of nothing only for an instant, but at any rate, I am both relaxed and tense in front of the mirror.” He replies briefly to their low-voiced question and they crown him with the other wig; now he exists alone before the mirror while the assistant behind him slowly unkinks each snarled hair, and he is so still while the kyogen bawls toward its boisterous end. The audience applauds. It is almost time. Five men attend him now, working at his wig, occasionally laughing very softly and gently together among themselves; and then at last the mask goes on, pale and unearthly against that black hair which they so carefully caress. They remove the mask, insert cushioning to increase its resonance for when he sings and, equally importantly, to move it farther forward, thereby widening its turning arc, and thus its expressiveness. (We will take up this subject later on.) Needless to say, the lowest objective in this fitting, if indeed it figures at all, is the actor’s comfort. The man who last smoothed his hair now kneels behind him at a discreet distance, closes his eyes, and, so it seems to me, prays, although Mr. Umewaka expressed surprise when I questioned him about this later. Meanwhile, each member of the chorus enters in turn and bows to Mr. Umewaka, who slightly inclines his head in return as he gazes into the mirror. The padded mask returns to his face. They raise his beautiful hair and tuck it just so around the face of Shuntoku-maru, the blind temple-haunting vagrant of the uncertain step.

WHAT IS NOH?

Opposing itself to the flickering of crowds across the wide white crosswalk-lines, the clatter of a million high heels through subway tunnels crammed with boutiques, the girls who dye their hair red, blonde or brown, the restaurant eels in crystalline tanks, the necktied salarymen rapt in their sadomasochistic comic books, the department stores excitingly bright with new electric goods, the clicking turnstiles, multistorey advertising screens, walkways and throughways, the vending machines so ubiquitous and diverse that they really ought to have their own Audubon field guide, the unending beeping and movement of Shinjuku Station at rush hour, the ball bearing music of pachinko parlors packed with gamblers all in rows, the breathlessly variable, deliciously novel, commercial, showy nowness of urban life, Noh offers us long silences punctuated by a single chant, every instant as perfect as an ideally composed photograph; time stops in order to show us that fact. Outside the Noh theater, everything is present; inside, everything is long past even when it happens. Outside, we find so many things to see and hear that all we can do is gather armloads of them, dropping some as we go; later we’ll remember just a few: a certain alley, face, toy, sign, price. Inside, Noh presents to us a single thing, which lives so slowly that we ought to be able to snatch it up and carry it off; frequently the performers fall inhumanly still; the electricity must have been turned off! The boredom which some people feel at Noh performances is in part self-defensive. If we can’t comprehend this one thing — Mr. Umewaka’s voice, half-spoken, half-sung, with its repeated patterns of cadence dwindling between silences — then what are we really coming away with? And why can’t we comprehend it? In the beginning, it’s easy to explain it away thus: Strangeness takes away all meaning. For example, a single voice moans: Ohh! and at intervals a drum strikes, and fingers flutter on it, then another mask, another ghost appears upon the bridge from elsewhere, and begins to chant, accompanied by perfect silence, with perfect silence between its own words: It’s chanting in strophes. This pale figure invades the stage; then the orange-brocaded woman whom Mr. Umewaka has become slowly follows it. The two make a colloquy, kneeling, facing one another across a glittering wooden distance, and then the chorus begins, the shoulder-drum commences to shake, the fluttering arm strikes it from beneath as the flute screeches with inexpressible unearthliness, the chorus’s voices rising and falling in almost wolflike fashion. What does this “mean”? What is being conveyed? I know the story; the abandoned wife in “Kinuta” is dying of loneliness and resentment; but were it a different, happier story, the music might still seem mournful to me. Mr. Umewaka himself, who first performed at age three, cheerfully acknowledged that his father and grandfather “just taught me the move, not the meaning. Later I tried to realize for myself what it meant.” Geisha dancers tell me much the same. But in time we do begin to know, and even predict a trifle; we’re taught what a certain gesture means, and these almost frozen figures on this nearly empty stage become larger, more complex, less explicable. Isn’t that what “reality” is? I love to rush through Tokyo and I could spend hours adoring a Noh mask. Could Noh someday teach me to be equally exalted in contemplating an oval of white paper? Noh is contemplation. In the bygone centuries of its origin, Noh was the expression of sacred teachings; in the case of such spectacles as “Okina,” which I’ll describe later on, it’s not inaccurate to speak of Noh rites.

“Is Noh secular or religious?” I once asked Mr. Umewaka.

“Of course it is closely connected to religious practice,” he replied, “but this has now become very difficult for the audience to understand. So we remove that element” — and I was shocked to hear him say that he was prepared to remove anything. “We emphasize the theatrical. In the past we invoked the blessings of Buddha. Now we strive to be actors.”

Indeed, to anyone lucky enough to attend a performance, Noh is a theater of upraised golden fans, shaken rattles, stone-faced, howling drummers, positional choreography (mark each performer’s homing-spot on stage, and from this alone you’ll know whether or not he’s the protagonist), of mummy-faced demons in gorgeous kimonos, long silences, ceremoniousness. The noises of the drums, wooden and musical at the same time, mark time’s spending of life and story as Mr. Umewaka raises his golden fan; the flute sounds; he slowly advances, then stamps, turns sideways, still more slowly traversing the stage, he and these other men expressing what at first seems to be the strictest, most severe stonefaced rigidity. Zeami, the fourteenth-century actor, composer and theoretician who with his father Kanami should be credited for much of Noh’s present day form, states in the introduction to one of his secret treatises that “all the exercises must be severely and strictly done: there must be no self-assertion.” It is precisely this which gives each performance what one observer labels “a religious and sober atmosphere of almost suffocating intensity, while the subtle and mysterious expression of the No mask reveals an extreme repression of joy and sorrow.” After silence, one drum begins to beat again; then the tempo increases, the audience reverently murmuring and pointing out this or that subtlety to one another. The drummers chant: “Yo — ho, yyyyyo!” and their percussive representation of emotion and time grows ever more rapid, in time with the swirling of Mr. Umewaka’s gilded fan, all sounds hollow and resonant, like life itself: significant, yet soon to be over. That fan’s movements are as carefully conventionalized as each actor’s place on stage. In Noh, as you might have realized by now, nearly everything is fixed, right down to the performers’ order of entrances and exits: “There must be no self-assertion.” When I asked Mr. Umewaka how it would be if I watched a Noh performance by two different masters, he insisted: “Well, they might do exactly the same thing but what the audience feels would be completely different.” So it is with the fan. Held to the actor’s temple, a fan can be a pillow; held lower, it might be a sake glass. At the end of “Yoro-boshi,” the waki, the foil who plays Shuntoku-maru’s father, opens his fan just before commencing to slowly glide after Shuntoku-maru on that long, pine-tree’d stage-bridge back to “reality’s” curtain. This gesture expresses joy in the reconciliation of father and son. The widening fan emerging from the waki’s heart, rising up and out, this gesture must express joy; it always expresses joy. In “Yoro,” which tells the tale of a magic spring, Mr. Umewaka manipulates the fan in such a way that any informed person will know that he is dipping water. And these various movements, like operatic motifs, can be combined, strung together: On the edge of the stage Mr. Umewaka kneels, gazing down through the fan into something far beyond “reality,” which Noh continually defies anyhow (the chorus can express a single character’s consciousness, and the lead actor may subdivide into different entities at any time). Slowly he rises, walking backward, raising the fan, ...