![]()

1

Introduction

In those days a decree went out from Caesar Augustus that all the world should be enrolled.

LUKE 2:1

From its very beginning, the Christian message was grafted onto human history. The Good News Christians have proclaimed through the ages is that in Jesus Christ, and for our salvation, God has entered human history in a unique way. History is crucial for understanding not only the life of Jesus, but also the entire biblical message. A good deal of the Old Testament is historical narrative. The Bible tells the story of God’s revelation in the life and history of the people of God. Without that story, it is impossible to know that revelation.

The New Testament writers are quite clear about this. The Gospel of Luke tells us that the birth of Jesus took place during the reign of Augustus Caesar, “when Quirinius was governor of Syria” (2:2). Shortly before, the same Gospel places the narrative within the context of Palestinian history, recording that it took place “in the days of Herod, king of Judaea” (1:5). The Gospel of Matthew opens with a genealogy that places Jesus within the framework of the history and hopes of Israel, and then goes on to date the birth of Jesus “in the days of Herod the king” (2:1). Mark gives less chronological detail, but still does affirm that Jesus began his ministry “in those days”—that is, the days of John the Baptist (1:9). The fourth gospel wishes to make clear that the significance of these events is not transitory, and therefore begins by stating that the Word who was made flesh in human history (1:14) is the same Word who “was in the beginning with God” (1:2). Finally, a similar note is sounded in the First Epistle of John, the opening lines of which declare that “that which was from the beginning” is also that “which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon and touched with our hands” (1:1).

After completing his gospel, Luke continued the story of the Christian church in the book of Acts. He did not do this out of mere antiquarian curiosity, but rather out of some important theological considerations. According to Luke and to the entire New Testament, the presence of God among us did not end with the ascension of Jesus. On the contrary, Jesus himself promised his followers that he would not leave them alone, but would send another counselor (John 14:16-26). At the beginning of Acts, immediately before the ascension, Jesus tells his disciples that they will receive the power of the Holy Spirit, by which they will be his witnesses “to the ends of the earth” (1:8). Then follow the events of Pentecost, which mark the beginning of the witnessing life of the church. Thus, the theme of the book commonly called Acts of the Apostles is not so much the deeds of the apostles, as the deeds of the Holy Spirit through the apostles (and others). Luke has left us two books, the first on the deeds of Jesus, and the second on the deeds of the Spirit.

But Luke’s second book does not seem to have a conclusion. At the end, Paul is still preaching in Rome, and the book does not tell us what becomes of him or of the other leaders of the church. Luke had a theological reason for this, for in his view the story he was telling shall not come to an end before the end of all history.

What this means for those who share in Luke’s faith is that the history of the church, while showing all the characteristics of human history, is much more than the history of an institution or of a movement. It is a history of the deeds of the Spirit in and through the men and women who have gone before them in the faith.

There are episodes in the course of that history in which it is difficult to see the action of the Holy Spirit. As our narrative unfolds, we shall find those who have used the faith of the church for their financial gain, or to increase their personal power. There will be others who will forget or twist the commandment of love, or will persecute their enemies with a vindictiveness unworthy of the name of Jesus. At other times, it will appear to many of us that the church has forsaken the biblical faith, and some will even doubt that such a church can truly be called Christian. At such points in our narrative, it may do well to remember two things.

The first of these is that, while this narrative is the history of the deeds of the Spirit, it is the history of those deeds through sinners such as we are. This is clear as early as New Testament times, when Peter, Paul, and the rest are depicted both as people of faith and as sinners. And, if that example is not sufficiently stark, it should suffice to take another look at the “saints” to whom Paul addresses his First Epistle to the Corinthians!

The second is that it has been through those sinners and that church—and only through them—that the biblical message has come to us. Even in the darkest times in the life of the church, there were those Christians who loved, studied, kept, and copied the scriptures, and thus bequeathed them to us.

What those earlier Christians have bequeathed to us, however, is more than the text of scriptures. They have also left the illuminating record of their striving to be faithful witnesses under the most diverse of circumstances. In times of persecution, some witnessed with their blood, others with their writings, and still others with their loving acceptance of those who had weakened and later repented. In times when the church was powerful, some sought to witness by employing that power, while others questioned the use of it. In times of invasions, chaos, and famine, there were those who witnessed to their Lord by seeking to restore order, so that the homeless might find shelter, and the hungry might have food. When vast lands until then unknown were opened to European Christians, there were those who rushed to those lands to preach the message of their faith. Throughout the centuries, some sought to witness by the Word spoken and written, others by prayer and renunciation, and still others by the force of arms and the threat of inquisitorial fires.

Like it or not, we are heirs to this host of diverse and even contradictory witnesses. Some of their actions we may find revolting, and others inspiring. But all of them form part of our history. All of them, those whose actions we admire as well as those whose actions we despise, brought us to where we are now.

Without understanding that past, we are unable to understand ourselves, for in a sense the past still lives in us and influences who we are and how we understand the Christian message. When we read, for instance, that “the just shall live by faith,” Martin Luther is whispering at our ear how we are to interpret those words—and this is true even for those of us who have never even heard of Martin Luther. When we hear that “Christ died for our sins,” Anselm of Canterbury sits in the pew with us, even though we may not have the slightest idea who Anselm was. When we stand, sit, or kneel in church; when we sing a hymn, recite a creed (or refuse to recite one); when we build a church or preach a sermon, a past of which we may not be aware is one of the factors influencing our actions. The notion that we read the New Testament exactly as the early Christians did, without any weight of tradition coloring our interpretation, is an illusion. It is also a dangerous illusion, for it tends to absolutize our interpretation, confusing it with the Word of God.

One way we can avoid this danger is to know the past that colors our vision. A person wearing tinted glasses can avoid the conclusion that the entire world is tinted only by being conscious of the glasses themselves. Likewise, if we are to break free from an undue bondage to tradition, we must begin by understanding what that tradition is, how we came to be where we are, and how particular elements in our past color our view of the present. It is then that we are free to choose which elements in the past—and in the present—we wish to reject, and which we will affirm.

The opposite is also true. Not only is our view of the present colored by our history, but our view of history is also colored by the present and by the future we envision. Were the reader to compare this Story with earlier histories of the church, some differences would immediately become apparent. For one thing, this Story seeks to acknowledge the role of women throughout the life of the church in a way that most earlier histories did not. This is not because the author has any particular insight that others do not. It is simply because our age has become much more aware of the significant contribution of women to every era, and particularly to the life of the church. Likewise, it will become apparent that the way I tell the story here, it does not make the church of the North Atlantic its culmination. Again, this is not due to some particular insight of the author, but simply to the astonishing events of the last two centuries, when Christianity first became a truly universal religion, and then became more and more a religion no longer dominated by the North Atlantic. It is rather the obvious conclusion of anyone looking at the statistics of the last few decades, as will be seen in Volume 2. At a time when there are more Christians in the former “mission fields” than in the “mother churches,” we must tell the story in a global way that was not necessary—and perhaps not even possible—in earlier generations. Thus, there are elements in the story that today seem most important to us, but were quite secondary to historians fifty years ago.

It is at this point that the doing of history converges with the making of it. When we study the life and work of past generations, and when we interpret it, we are doing history. But we must remember that we are reading the past in the light of our present, and also that future generations will read about our times as past history. In that sense, like it or not, both by our action and by our inaction, we are making history. This is both an exhilarating opportunity and an awesome responsibility, and it demands that we do history in order to be able to make it more faithfully. Every renewal of the church, every great age in its history, has been grounded on a renewed reading of history. The same will be true as we move ahead into the twenty-first century.

In this new century, as in every age, Christians face new and unexpected challenges. In seeking to be obedient in our response to such challenges, we have the resources of past times when other believers found themselves in similar situations. The response of the early church to a culture that often saw it with indifference or even contempt may provide guidance at a time when similar attitudes prevail in much of Western society. The manner in which the church in the fourth and fifth centuries responded to the migration of entire nations may provide insight into possible ways to interpret and to respond to the demographic upheavals of our time. The devotion of medieval scholastics and of Protestant Reformers may be an inspiration to budding scholars and theologians. The history of missions in the nineteenth century may well warn us of the pitfalls the church faces when it crosses cultural and social boundaries. In all of this, the past will illumine the present.

But the opposite is always true: As we look at those and other past times and events, we do so through the lens of our own time, our own concerns, our own hopes. History is not the pure past; history is a past interpreted from the present of the historian. Thus, our understanding of the early martyrs and heretics, of monastics, pastors, crusaders and scholars, as well as our understanding of everyday Christian life in the past, will be both marked and enriched by our present-day lenses.

It is into this dialogue that we now enter.

![]()

PART I

THE EARLY CHURCH

![]()

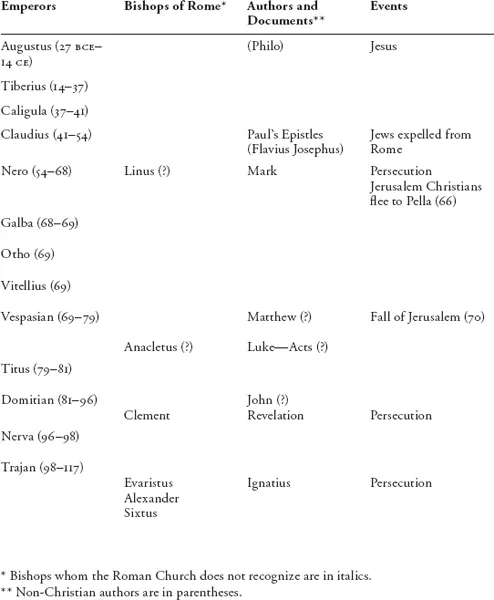

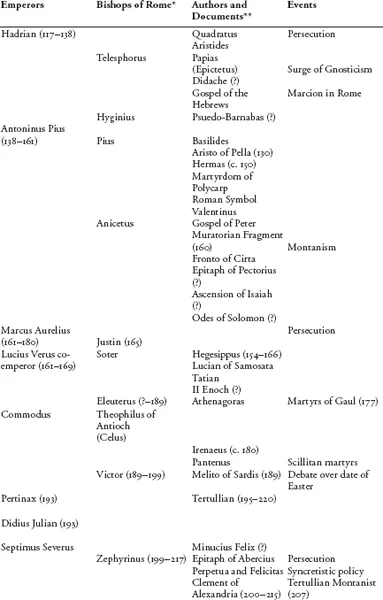

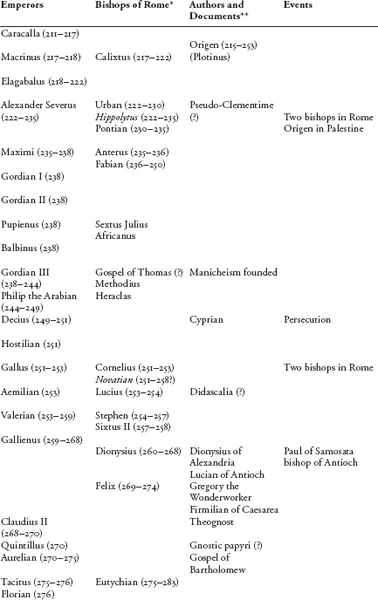

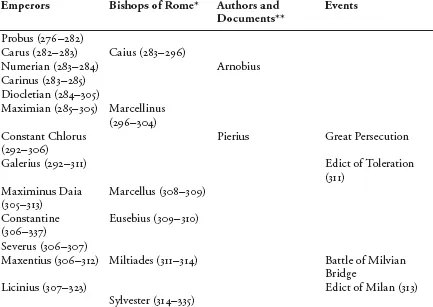

Chronology

![]()

2

The Fullness of Time

But when the time had fully come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the Law.

GALATIANS 4:4

The early Christians did not believe that the time and place of the birth of Jesus had been left to chance. On the contrary, they saw the hand of God preparing the advent of Jesus in all events prior to the birth, and in all the historical circumstances around it. The same could be said about the birth of the church, which resulted from the work of Jesus. God had prepared the way so that the disciples, after receiving the power of the Holy Spirit, could be witnesses “in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria and to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8).

Therefore, the church was never disconnected from the world around it. The first Christians were first-century Jews, and it was as such that they heard and received the message. Then the faith spread, first among other Jews, and eventually among Gentiles both within and beyond the borders of the Roman Empire. In order to understand the history of Christianity in its early centuries, we must begin by looking at the world in which it evolved.

JUDAISM IN PALESTINE

Palestine, the land in which Christianity first appeared, has long been a land of strife and suffering. In ancient times, this was due mostly to its geographical position, at the crossroads of the great trade routes that joined Egypt with Mesopotamia, and Asia Minor with Arabia. As we read the Old Testament, we see that, as empires came and went, they cast a covetous eye on that narrow strip of land. For this reason, its inhabitants repeatedly suffered invasion, bondage, and exile. In the fourth century BCE, with Alexander and his Macedonian armies, a new contender entered the arena. Upon defeating the Persians, Alexander became master of Palestine. But his death followed shortly thereafter, and his vast empire was dismembered. For a long time, two of the resulting dynasties, one in Egypt and one in Syria, fought for possession of Palestine. The result was another period of unrest and political instability.

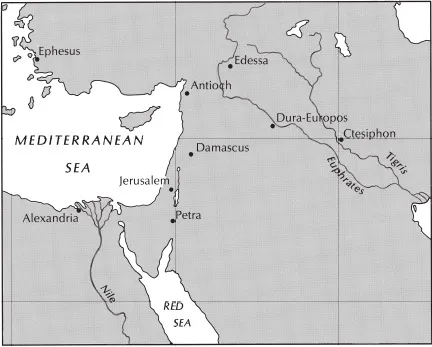

Palestine: Birthplace of Christianity.

The conquests of Alexander—like most imperialist enterprises—sought to justify themselves on an ideological basis. He did not wish simply to conquer the world, but to unite and enrich it by spreading the insights of Greek civilization. The result, in which some elements of Greek origin combined with other elements taken from conquered civilizations in various forms and degrees, is known as Hellenism. Although the precise nature of Hellenism varied from place to place, it did provide the eastern Mediterranean basin with a unity that opened the way first to Roman conquest, and later to the preaching of the gospel.

But there were many Jews who did not regard Hellenism as a blessing. Since part of the Hellenistic ideology consisted of equating and mixing the gods of different nations, they saw in it a threat to Israel’s faith in the One God. In a way, the history of Palestine from the time of Alexander’s conquest to the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE may be seen as the constant struggle between Hellenizing pressures on the one hand and Jewish faithfulness to their God and their traditions on the other.

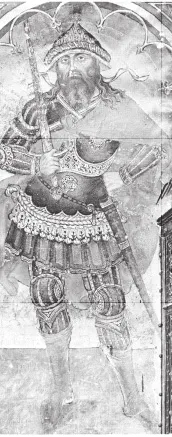

Under the leadership of Judas Maccabaeus, the Jews enjoyed a period of political freedom. Here he is seen as depicted by the fifteenth-century Italian painter Taddeo di Bartolo.

The high point of that struggle was the Jewish rebellion led by the family known as the Maccabees, in the second century BCE. For a while the Maccabees were able to gain a measure of religious and political independence. But eventually their successors gave way to the Hellenizing pressures of the Seleucids, who had succeeded Alexander in the rule of Syria. When some of the stricter Jews protested, they were persecuted. Partially as a result of all this, Rome eventually intervened. In 63 BCE, Pompey conquered the land and deposed the last of the Maccabees, Aristobulus II.

As Alexander had earlier, the Romans justified their imperial conquests by means of an ideology. Their calling was to civilize the world around them—which to them meant building and beautifying cities similar to Rome, and placing all of them under Roman rule and guidance. (Note that etymologically the word “civilization” may be understood as “cityfication”.) Where there were no cities, they built new ones. And where there were ancient cities, they embellished them and erected public buildings in the style of Rome itself.

In general, Roman policies toward the religion and customs of conquered people were rather tolerant. Shortly after the conquest, the Roman government gave the descendants of the Maccabees a measure of authority, and used them in governing the land, givin...