![]()

CHAPTER ONE

“Wild and Wooly”

The party started from New Haven late in June, bound for a West that was then really wild and wooly.

—GEORGE BIRD GRINNELL,

Memories

The adventure that changed the course of George Bird Grinnell’s life began with a train, and the path of the train, as it crossed the plains in the summer of 1870, was blocked by buffalo.

The new transcontinental railroad, like the wagon trails that preceded it, hewed to the valleys. Far from “featureless,” as the Great Plains is frequently described, it is a region whose signature characteristic is so pervasive as to overwhelm—an openness so vast that the newcomer has no antecedent to place it in context. Coming, as Grinnell did, from the East, with its hemmed-in horizons and creeping green, arrival on the stark prairie was a shock to the system, an obvious demarcation of a place that was new. It was also, in the summer of 1870, a place that was wild.

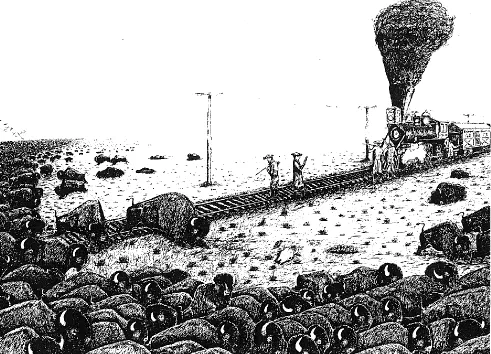

As the train glided along the tracks, Grinnell heard the sudden screech of metal brakes and excited shouts. Looking out the window, he saw a herd of buffalo. After a brief delay, the herd wandered off and the voyage continued. Later, though, the train was halted a second time by another herd. “We supposed they would soon pass by,” remembered Grinnell, “but they kept coming … in numbers so great that they could not be computed.” It took three hours for the herd to cross the tracks.1 In the early days of the railroad, the problem of buffalo blocking tracks was so common that engines were sometimes equipped with a device that shot out steam to scatter the herd.

For the nineteenth-century traveler, no sight better symbolized arrival in the West than the buffalo. Grinnell, who would turn twenty-one in two months, had arrived in the midst of his boyhood dreams. He certainly spoke volumes about his own motivations when he later wrote that “none of [us] except the leader had any motive for going other than the hope of adventure with wild game or wild Indians.”2

Grinnell and his young companions certainly looked prepared for adventure. Each of the young men carried a shiny new Henry repeating rifle, a pistol, bandoleers of cartridges, and a Bowie knife. Never mind that few had any experience with weapons (Grinnell was one who did). In Omaha, they had walked out onto the prairie “to try our fire arms.” Grinnell, at least, was under no illusion: “The members of the party were innocent of any knowledge of the western country, but its members pinned their faith to Professor Marsh.”3

“We supposed they would soon pass by, but they kept coming … in numbers so great that they could not be computed.” A Hold–Up on the Kansas–Pacific, 1869, by Martin Garretson. Courtesy of the National Museum of Wildlife Art.

Eyes to the West: George Bird Grinnell in his early twenties.

Courtesy of the Scott Meyer family.

George Bird Grinnell was born on September 20, 1849, in Brooklyn, the first of five children to Helen A. Lansing and George Blake Grinnell. Grinnell’s father began his career as a successful dry-goods merchant and ended it as a prominent merchant banker—the “principal agent in Wall Street of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt.”5

As a young George Bird Grinnell contemplated his future, the path of least resistance seemed to flow naturally toward a position as a captain of finance in a world ruled by the class to which he was born. Certainly this was the direction that his father and mother would push. Instead Grinnell would one day rise to challenge the foundational tenets on which his world had been built.

The events that put Grinnell on a different course began on New Year’s Day, 1857. He was 7 that year, and his father moved the family to the country. They rented at first, eventually building a house on a large tract of land in a part of Manhattan known as Audubon Park. The entire area once had been owned by John James Audubon, the famous painter-naturalist. Today, the quarter has been swallowed whole by New York City, bounded by West 158th and West 155th streets to the north and south, the Hudson River and Amsterdam Avenue to the east and west. In 1857, though, New York City was far away. Access to the city was by the Hudson River Railroad or by wagon, a trip of one and a half hours over hilly terrain.

Though John James Audubon had been dead for six years when the Grinnells moved to Audubon Park, much of the artist’s family was still in residence. Audubon’s two adult sons, Gifford and Woodhouse, continued the painting and publishing enterprise of their father. Each had a family and a house of his own on the property. Lucy Audubon, the elderly widow of the artist, lived with Gifford.

For a young boy, Audubon Park was an idyllic playground, like living in an engraving from Currier & Ives. “In the early days of Audubon Park almost nothing was seen of what in later days was called ‘improvement,’“ as Grinnell later described it. “The fields and woods were left in a state of nature.” There were great groves of hemlock, chestnut, and oak. Springs flowed up from the ground and brooks tumbled down to the Hudson. There were stables with horses, pens of cattle and pigs, free-roaming chickens, geese, and ducks. The land was wild enough to be thick with small game, songbirds, and birds of prey, and Grinnell remembered a time when three eagles fought for a fish on his front lawn.6

Between the Grinnells, the Audubons, and the handful of other families who inhabited Audubon Park, a veritable tribe of young children roamed the whole area at will. Grinnell’s boyhood memories, which he recorded in an unpublished document for his nieces and nephews, read like Tom Sawyer—an almost mythic childhood of unsupervised adventure and delightfully harmless delinquency. Grinnell and his cohorts stalked birds with bow and arrow, collected clams in the tidal pools along the Hudson, and stole chickens for “surreptitious roastings at fires in the woods.” There were swimming holes in ponds and on the sandy beaches of the river. Boat docks provided a too-tempting platform for diving into the water, causing complaints from train passengers about naked children (Grinnell and his friends) “dancing on top of the piles, and generally making an exhibition.” An ordinance was passed requiring swimmers to wear “tights,” and when Grinnell and a friend ignored it, a policeman hauled them off to jail. “An hour or two of this confinement gave us plenty of time to ponder on the sorrows of life.” A judge eventually sent them home.7

Grinnell’s own imagination provided ample fuel for his childhood play, but an additional source helped to animate his boyhood adventures. Though barely known today, one of the most popular novelists of the mid-nineteenth century was an Irishman named Thomas Mayne Reid. Reid came to America in search of adventure in the 1840s. He found it, among other places, by enlisting with the U.S. Army during the war with Mexico. He earned a commission and fought in battles including Vera Cruz and Chapultepec, where he was seriously wounded. After the war, Reid began writing novels, most based loosely on his time in the American Southwest. He used the pen name Captain Mayne Reid, and his books, with titles such as The Rifle Rangers, The Scalp Hunters, and The War Trail, struck with particular resonance among young boys—and certainly with Grinnell. “His stories had appealed to my imagination.” Indeed many of the heroes in Reid’s books were boys, as in The Young Voyageurs, with the subtitle The Boy Hunters in the North, and The Boy Hunters, subtitled Adventures in Search of a White Buffalo.8

There were no buffalo of any shade near Audubon Park, but Grinnell found many opportunities to act out the scenes he devoured from the books of Captain Reid. “It must have been 1860, or possibly 1861, when I was eleven or twelve years old, that I first began to go shooting.” Knowing that his parents would disapprove, Grinnell and a friend began secretly borrowing an old military musket from the village tailor. The gun was far taller than either boy and was so heavy that “neither could hold it to the shoulder” by himself. They took turns firing by having one boy, the shooter, rest the gun on the other’s shoulder. No creature was safe. “Small birds were the chief game pursued … meadowlarks, robins, golden winged woodpeckers and occasionally a wild pigeon.” Later one of Grinnell’s uncles legitimized the hunting activity when he gave Grinnell a small shotgun of his own.9

In Grinnell’s writings about his childhood, no topic receives more attention than hunting. Indeed hunting became Grinnell’s most important early connection to the wild world, teaching him skills in the close observation of nature. Hunting also provided a new tie to the Audubon family. One of Grinnell’s frequent field companions was Jack Audubon, grandson of the painter. The connection went deeper still. Jack, in Grinnell’s words, “was privileged” with carrying his grandfather’s rifle—the same weapon that John James Audubon had relied upon during his epic adventures across the Mississippi.10

Audubon Park steeped young George Bird Grinnell in other icons of the West, a “region which in those days seemed infinitely remote and romantic with its tales of trappers, trading posts and Indians.” The houses of Audubon’s two sons were like museums, their walls adorned with trophies of deer and elk, powder horns, and ball pouches. A portrait of the buckskin-clad artist stared down, along with dozens of his paintings. In the barn, where the boys often played, were “great stacks of the old red, muslin-bound ornithological biographies and boxes of bird skins collected by the naturalist, and coming from we knew not where.” Because the artist’s sons carried on his work, they corresponded with scientists from around the world, and “frequently received boxes of fresh specimens.” Grinnell remembered crowding around newly arrived shipments with his friends, waiting breathlessly for the cartons to be opened, then gazing in wonder at the “strange animals that were revealed.”11

Of all the members of the Audubon family, none would exert greater influence on the young Grinnell than Lucy, the septuagenarian widow of the artist. Grinnell described her as “a beautiful white-haired old lady with extraordinary poise and dignity; most kindly and patient and affectionate, but a strict disciplinarian and one of whom all the children stood in awe.” From her bedroom she ran a school for the children of the neighborhood. Some of them were her grandchildren; all of them called her “Grandma Audubon.”12

Lucy Audubon appears to have been one of those unique teachers—a lucky person might encounter one or two—who changes the lives of their students. She understood the children she taught, grasping the significance of those fleeting moments of connection when an educator has an opportunity to impress a young mind. “If I can hold the mind of a child to a subject for five minutes,” she said, “he will never forget what I teach him.”13 George Bird Grinnell, certainly, would always remember.

John James Audubon: Grinnell spent his childhood roaming the grounds of the (then rural) New York estate of the former painter-naturalist.

Courtesy of the National Park Service.

Some of the lessons were mundane: reading, writing, and ‘rithmetic. Others were more unique: Lucy Audubon had worked closely with her husband on some of his later writings, including his Ornithological Biography. The experience had given her a solid exposure to natural science, a knowledge she passed on to her pupils. This knowledge—and Grinnell’s close relationship with his teacher—were on display in a story Grinnell later recounted about a time he captured a live bird in a net. “I rushed into the house and up to Grandma’s room, and showed her my prize. She told me that the bird was a Red Crossbill—a young one—pointed out the peculiarities of the bill, told me something about the bird’s life, and later showed me a picture of it. Then after a little talk she and I went downstairs and out of doors, found the birds still feeding there, and set the captive free.”14

Some of the lessons that Grinnell learned from Lucy Audubon—including the one that would later emerge as the central creed of his life—would not register for years. Indeed from the time Grinnell left the school of Grandma Audubon to the time he graduated from college, his life had the feeling of casual indifference and missed opportunity.

His wealthy parents sent him to the best secondary schools. In 1861, when George was 12, he began a two-year stint at Manhattan’s French Institute. At age 14 he enrolled in the prestigious Churchill Military School at Sing Sing. Churchill enforced a mild form of military discipline, but the accommodations were hardly spartan. The supplies that new students were instructed to bring to school included “napkin ring, bathrobe and slippers, mackintosh and umbrella, sponge and nail file.” For three years, Grinnell went obediently through the well-defined motions of the school. He eventually rose up the ranks t...