![]()

Lecture 1

Preliminary discussion

Although this is a course in archaeology, it also deals with many problems which derive from biology, including the study of bones, the decomposition of the corpse and the products of decomposition. Our task is to use these studies in order to understand cultural phenomena, which bring us back to the sphere of archaeology and, more specifically, funerary archaeology. This approach was developed in France twenty-five years ago in the early 1980s when rescue archaeology was being established. Initially this new subject was called ‘l’anthropologie du terrain’. This formulation was very successful due to its apparent clarity for French archaeologists, ‘l’anthropologie du terrain’ being the discipline in which the person studying human bones, the anthropologist, whilst being a biologist does not only work in the laboratory but also in the field, i.e. on archaeological excavations, in order to participate directly in the collecting and recording of data.

Today however this expression should be abandoned, in order to prevent confusion with other disciplines. In France and other neo-Latin countries, following the definition that has long prevailed along the lines established by Paul Broca, anthropology is the discipline that studies the human being in his/her biological dimension. In Anglo-Saxon and northern European countries however, anthropology takes into account both biological and cultural dimensions of human behaviour. In the U.S.A., for example, the term ‘anthropology’ has the same meaning that we give to ‘ethnology’ and the adjective ‘physical’ must be added to distinguish the area of the discipline which primarily concerns biological parameters. This meaning is gaining increasing international acceptance. Archaeology therefore, in its ‘ethnological’ approach to the study of ancient populations, is called ‘Palaeoethnology’. If we consider the time dimension, archaeology is then an anthropological discipline like history or linguistics. Moreover from the archaeological point of view, ‘field’ refers to ‘excavation’. But an anthropologist-biologist who goes for example to Africa to study the demographic consequences of rubella vaccination also carries out ‘fieldwork’ which is different from excavation. To avoid confusion Bruno Boulestin and I (2005) therefore suggested the use of the term ‘archaeothanatology’, since ‘thanatology’ studies the biological and social components of death.

The simplest and most direct way to understand the nature of a discipline is to sample its bibliography. The first step naturally is to identify the authors of works published in this area. Generally however articles on burials are written by the archaeologists who excavated them and are rich in information of an archaeological type which relates to their specific training. This may differ from country to country and, even within a single country, between universities. Archaeological education is generally based both on learning to read stratification (the point of departure for all archaeological activity), to recognise layers, stratigraphic units, fills and so on. Another area concerns the analysis of material culture such as grave goods (e.g. weapons, pottery) and architectural structures. Training which includes the study of human bones is rare. There are not many university courses in osteology for archaeologists, in France at least. This subject is more specifically taught in biology and, above all, in medicine.

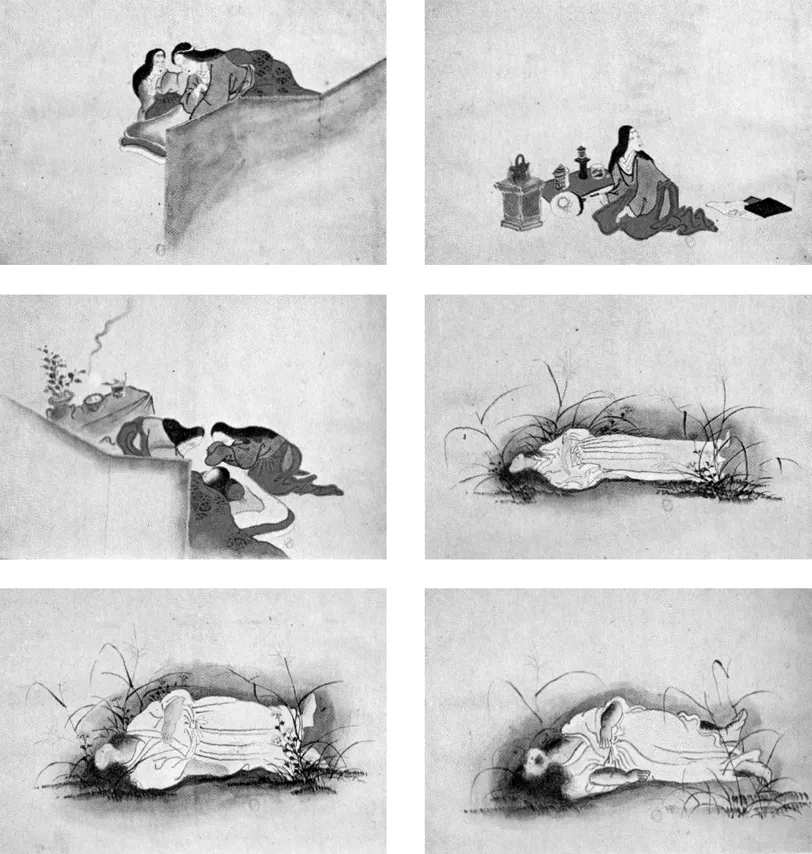

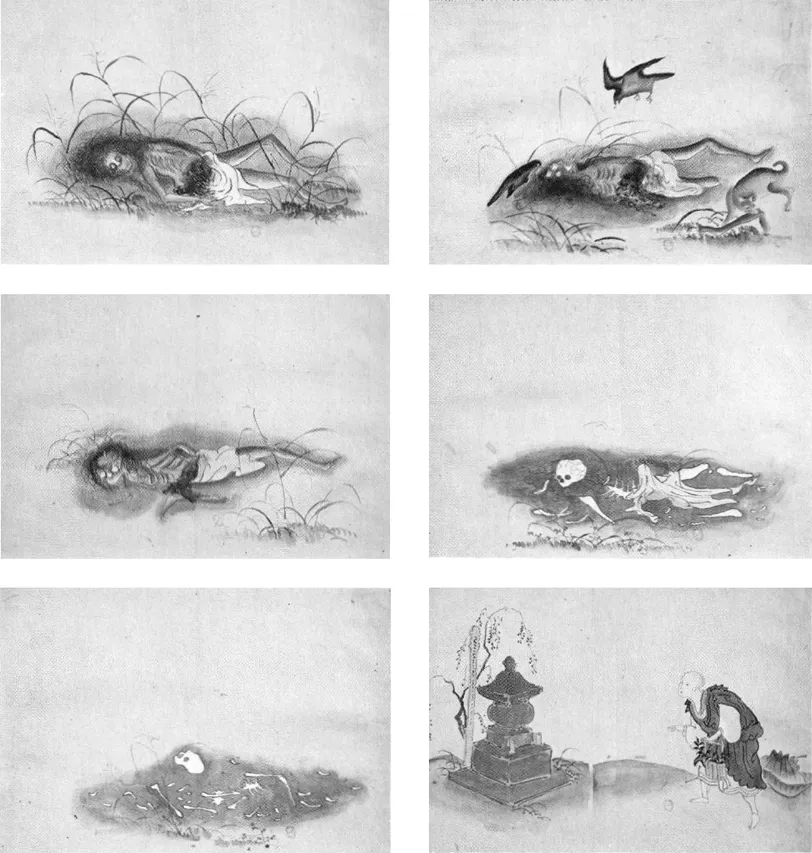

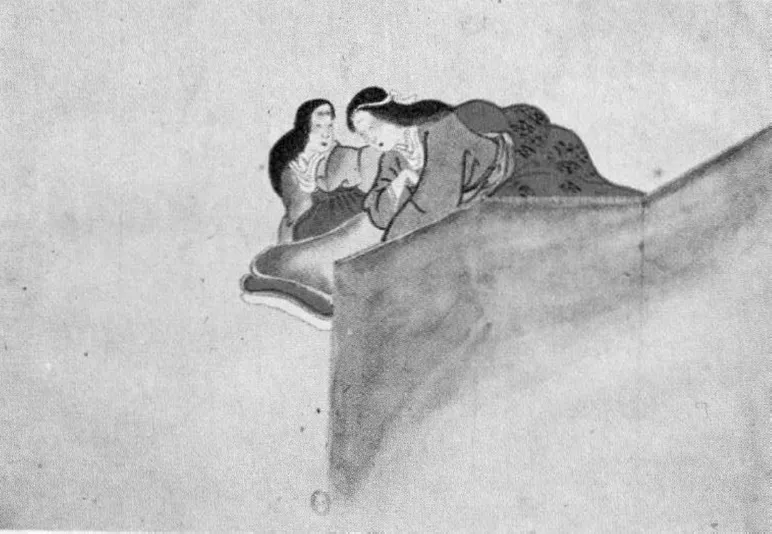

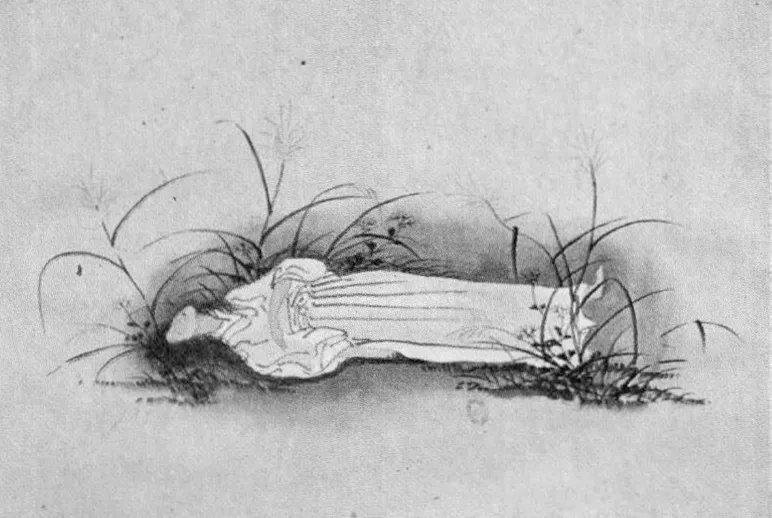

Figure 1. Japanese watercolour of the early 19th century (from E. Georges (1982) Voyages de la Mort. 265, Paris, Berger-Levrault). Photograph by J. L. Charmet.

When reading specialist publications we often then face a clear inversion in the hierarchy of importance of the different elements of the burial. The impression is often given that a corpse accompanies the brooch or the vessel, but the most important element of the burial is not the furnishing but the deceased: the brooch is not buried, but the deceased with the brooch.

The objective of ‘archaeothanatology’ is to reconstruct the attitudes of ancient populations towards death by focusing on the study of the human skeleton and analysing the acts linked to the management and treatment of the corpse. These are intended to enable the survivors to overcome the pain of this final parting and the unbearable anxiety that the bodies of relatives or friends are doomed to decompose. For that reason, funerary archaeologists should have a training to be applied in the field which is not limited to collecting human bones and taking them to laboratories. The responsibility for this disfunction should not be laid at the doors of archaeologists alone. In the past (and often still today), many anthropologists conceived of their work as being restricted to the laboratory and their dialogue with archaeologists was limited to asking where the bones came from and their date. Having obtained this information, the anthropologist applied the methodology of his/her own discipline, beginning what s/he considered to be his/her work, measuring morphological, morphometric and, if necessary, pathological characteristics of the bones. We should not forget that morphological anthropology is also a historical discipline, in that (like archaeology) it aims to understand the history of populations. Yet this approach to historical knowledge is situated at the very general level of population dynamics. It contributes in only an incomplete way to the understanding of the individual funerary complex.

While on the one hand archaeologists often lack sufficient training in anatomy to record the data related to the arrangement of human remains, on the other anthropologists/biologists do not have a real insight into archaeological issues, and the deceased is therefore excluded from overall assessment of the tomb. The bones are treated as extraneous elements, often published in appendices and therefore totally dissociated from the archaeological analysis. This is an epistemological aberration: the dead body is the raison d’être for the tomb and the central element around which, and in function of which, the acts were performed which funerary archaeology aims to reconstruct. The methodological choice for ‘l’anthropologie du terrain’ or ‘archaeothanatology’ consists simply of placing the deceased at the centre of interest in the tomb. This does not mean an undervaluing of the importance of grave goods, the social dimension of which is linked directly to funerary ideology and which often provides information for dating the grave. The fact that individual burials comprise perfect examples of closed contexts has given grave goods an essential role in reconstructing the relative chronology of different types of artefacts. But to use the grave goods found in the tomb to study, for example, the geographical distribution of an object (such as vessels from a particular production centre), belongs to economic rather than funerary archaeology.

1.1. Funerary archaeology and corpse taphonomy

To understand a burial is to bear in mind, above all, that skeletons were once corpses. To illustrate this point, we shall examine an early nineteenth century Japanese watercolour (Figure 1) comprising 12 vignettes showing the decomposition of a corpse which the artist must have carefully observed to represent so faithfully. Figure 1a represents the phase before death, with a woman lying on her bed protected by a screen. In Figure 1b, a servant or a relative seems concerned and alert. The following image (Figure 1c) shows the woman, now dead, and people beside her intent on the pre-burial treatment of the corpse, while an incense burner smokes on a table. This phase will interest the archaeologist who investigates the society in which the woman died and the causes of her death.

Figure 1a. Detail of Figure 1, first scene.

Figure 1b. Detail of Figure 1, second scene.

Figure 1c. Detail of Figure 1, third scene.

Figure 1d. Detail of Figure 1, fourth scene.

The following image represents the funerary deposit proper (Figure 1d): the corpse has been placed in an open space, a garden. The woman is laid on her back, dressed in a white tunic. Her left forearm is folded on her chest. Decomposition starts at the very moment of death, but sometimes may begin while the subject is still alive, when necrosis of tissue that is no longer supplied with blood takes place. The decomposition of the corpse takes place because of the action of two general factors, endogenous factors operating inside the corpse and exogenous factors working outside it. The endogenous factors are primarily bacteria, as well as fungi, mostly found along the digestive tract of the deceased. While we are alive our body keeps their proliferation under control but after death these micro-organisms multiply rapidly and attack the body of the individual. There are two immediate consequences, temperature increase and the production of gas. The corpse swells, increasing in volume (Figure 1e) and some parts become coloured brown and grey by post mortem lividity (Figure 1f). In an open space the swollen abdomen can even burst if the temperature is high enough (Figure 1g). This phenomenon does not occur if the corpse is buried in the ground. In the image we see that the upper left limb, initially laid on the chest, has fallen to one side. Therefore, the position of the skeleton in excavation may be different from the one which it assumed when deposited. Organic elements, such as clothing, generally decay together with the corpse. Figure 1h shows the intervention of exogenous elements. For example birds, like corvidae, may alight on a dead body to eat what remains of the eyes. A dog also carries off part of the lower right limb in its mouth. Figure 1i shows a corpse, partially defleshed, without its left leg and right foot. The exogenous elemen...