![]()

1

An introduction

Introduction

In this first chapter I introduce the study area, the Irish Sea zone, and detail how I have defined this area in this volume. This is not the first study to consider the Irish Sea zone and as such I also summarise previous studies of this area. I outline what this volume hopes to achieve with a consideration of the Neolithic of the Irish Sea zone, in particular a study of the landscape settings of the chambered tombs of this area, which is the focus of the volume.

Introducing the study area

To start off with, I would like to discuss why I have chosen the Irish Sea zone as a study area and then describe how I defined this study area. I should state from the start that the aim of this volume is not to suggest that the Irish Sea zone is, or ever was, a bounded entity. I am also not trying to claim that there was such a thing as a shared Irish Sea cultural identity. However, all archaeological studies require boundaries of some kind, this study being no exception and there are a number of justifications for choosing the Irish Sea zone as an area of study. Firstly, apart from early culture-historical approaches (e.g. Piggott 1954), there has been a tendency in the past (although with some key exceptions: see below) to study either side of Irish Sea separately. Scholars have tended to study either one side or the other of the Irish Sea zone. This is in part due to long-standing and excellent traditions of the study of prehistoric remains in Ireland, England, Scotland and Wales, which reflect modern political administrative boundaries (e.g. the survey work done by the Royal Commissions). However, the Irish Sea area has clearly been important for many thousands of years. From more recent periods, there is clear evidence of interaction (see various papers in Bowen 1970).

In this study I have used a number of criteria to help define the Irish Sea zone. Partly, the Irish Sea zone is simply those parts of the landscape which border onto the sea. There is of course an issue here: how ‘close’ does one have to be in order to be considered in the study? I did not want to use a simple cut-off distance (e.g. sites must be a maximum of 10km from the sea in order to be included) as sometimes this approach is too rigid and does not take into account the evidence. A good example of how such an approach is inappropriate is in relation to the setting of chambered tombs. There are examples where a site is located on the coastline, but the sea is not visible. At such a site you could argue that the main focus is not the sea, although quite clearly this site should be included in the study. However, sites located much further away from the sea often have spectacular views with wide vistas of the sea. At these sites you could suggest that the sea was a major focus of the landscape setting of the site, but if they fell outside a random cut-off distance then they would not be included. A more contextual definition was therefore required.

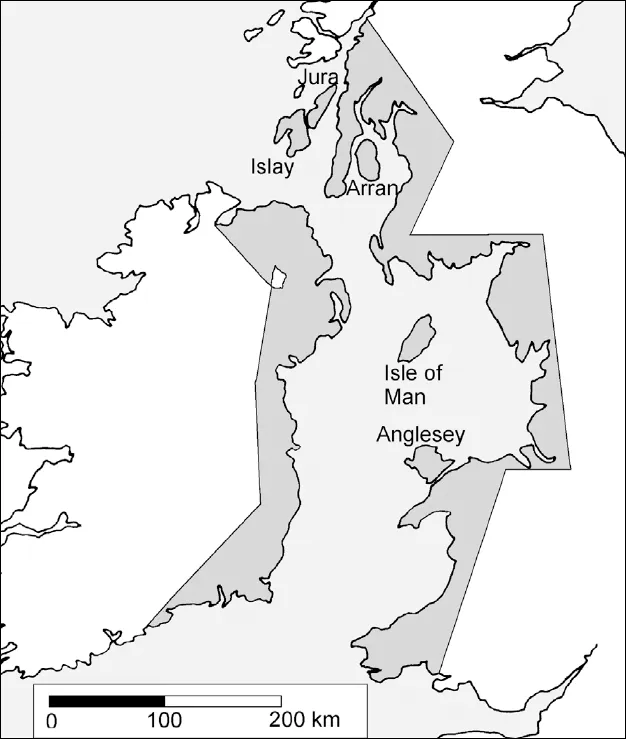

However, the precise definition of the study area was ultimately defined by the chambered tombs themselves. The focus of this volume is, after all, on the early Neolithic chambered tombs, and there is a clear and distinctive distribution of these sites in the Irish Sea zone. There is a clear distribution of monuments on the eastern seaboard of Britain, with a ‘blank’ area beyond: this blank area has been used to mark the boundary of the Irish Sea zone in this study. On the eastern side, I have taken the Irish Sea zone to comprise west Wales (as defined by the distribution of chambered tombs), the west coast of northern Britain (essentially Merseyside, Lancashire and Cumbria, none of which have any early Neolithic chambered tombs), and coastal south and western Scotland (as defined by the distribution of Clyde cairns). This eastern side of the Irish Sea incorporates a number of islands with chambered tomb architecture: Arran, Islay and Jura all have chambered tombs, as does Anglesey. The Isle of Man sits at the very heart of the Irish Sea zone (see Fig. 1.1).

The western side of the Irish Sea zone was initially harder to define. In Ireland, the distribution of chambered tombs alone does not define the study area. This is because there is no clear and obvious break in the distribution of monuments, particularly in the north where court cairns are found across the northern part of Ireland (from Antrim and Down to Mayo and Sligo). Yet by taking into consideration the classification of the sites and their overall topographic setting, it was possible to define the edge of the study area. There are differences between the central court cairns of western Ireland and the single façade court cairns of eastern Ireland, which made it obvious that there were real differences between east and west in the broadest sense. In the north, the final decision was informed by the topography: Lough Neagh acts as a good cut off point in the centre of northern Ireland and there are less monuments to the west of it. All of the monuments in counties Antrim, Down and Louth were therefore included, as were most of those in Armagh and Derry, with a couple in Tyrone. Only one court cairn is to be found south of Louth all the way down in County Waterford, which was also included. Ultimately, then, a combination of topography and the distribution of different styles of court cairns defined the Irish Sea zone in the north. Portal and passage graves within this area were also visited, although there are only a few of these sites.

Figure 1.1. The Irish Sea zone: the areas included in this study

In the southern half of Ireland there are two different dominant styles of monument: dolmens and passage graves. The passage graves were easy to deal with here: the larger passage graves are almost certainly later in date than the earlier traditions of dolmens and court cairns. Therefore, I removed the large middle Neolithic passage graves from the distribution. This left just dolmens which cluster quite clearly in the south-east of Ireland anyway. So, in the southern part of Ireland, this creates a very clear distribution of sites, incorporating the modern day county boundaries of Dublin, Wicklow, Carlow, Wexford, Kilkenny and Waterford (see Fig. 1.1).

So while the case study area presented in this volume is based around the distribution of megalithic architecture, as we will see other similarities either side of the Irish Sea also suggest that this zone is a worthy study area (see chapters 3 and 4). The selection of this study area was further justified once the results of the study were completed (see chapters 6 and 7) and I will discuss the entire area once again in chapter 8.

The significance of the Irish Sea zone

This is not the first piece to examine the Irish Sea zone as a case study. In fact, there is a long history of research into the area which suggests that this was an area of considerable significance in the past. An early reference to the Irish Sea is by Mackinder 1902 (in Bowen 1970) who referred to it as the ‘British Mediterranean’. The Mediterranean of course has been an important waterway for thousands of years, enabling trade and the movements of people from all the adjacent landmasses as well as being the focus of settlement. This idea was subsequently picked up by others (e.g. Crawford 1912; Fleure 1915), and in 1932 Fox’s The Personality of Britain suggested considerable interactions across the Irish Sea in the past (Fox 1932). In an important paper, Davis (1945) discussed the distribution of monuments around the Irish Sea zone and possible movements around this area by sea. This paper really marks the heyday of considerations of the Irish Sea zone within a culture-historical framework, an issue discussed and debated by many in the 1950s and 1960s (e.g. Daniel 1941; de Valera 1960; Piggott 1954). At this stage, the search was on for pinpointing the origins of various culture groups in Britain which were thought to originate in the Mediterranean. The Irish Sea was considered one of the areas which saw primary colonisation which then spread to other parts of the British and Irish Isles, an idea which culminated with the publication of The Irish Sea Province in Archaeology and History (Moore 1970).

The edited volume by Moore (1970) was already rather outmoded when published as the late 1960s saw an increased emphasis on regional variation and less explicit discussion of the movements of people across the Irish Sea. Regional sequences were investigated in detail at this time, divided up along modern political boundaries: de Valera’s work in Ireland (de Valera 1960; de Valera and Ó Nualláin 1961; 1964; 1972), Henshall and Scott’s work in Scotland (Henshall 1963; 1972; J. Scott 1969) and Lynch’s work in Wales (Lynch 1969b; 1972). These pioneering studies have led the way for later scholars to consider regional sequences in ever increasing detail, and an understanding that things were not the same throughout this area (see subsequent chapters for details). This is not to suggest, however, that the Irish Sea zone has fallen completely out of favour. Two papers in the late 1980s/early 1990s again highlighted the importance of the Irish Sea zone as an area of interaction and exchange in prehistory (Lynch 1989; Waddell 1991) and a subsequent edited volume has further considered these issues (Cummings and Fowler 2004c). Throughout the volume I return to the issue of interactions across the Irish Sea, again in more detail in the final chapter.

Overall aims of the volume

At one level, the volume is designed to give a broad and simple introduction to the Mesolithic and Neolithic of the Irish Sea zone. It is aimed to provide a summary of previous work for students who are less familiar with this area than the Neolithic archaeology of, say, Wessex or Orkney. It also offers a starting point for those wishing to read more extensively about the Irish Sea zone. The main focus of the volume is on the early Neolithic chambered tombs of the region and that an understanding of these monuments cannot be gained without a broader consideration of their landscape settings. I look in detail at the landscape setting of the chambered tombs of the Irish Sea zone, both overall and in more detail through a number of specific case studies. My consideration of landscape has been inspired by recent archaeological and anthropological literature on the significance of landscape (see chapter 6), yet the scale of analysis incorporates a much wider area than has been previously considered by these approaches. One aim is therefore to try and incorporate my landscape analysis into a broader understanding of the Neolithic sequence in this area and beyond.

Other key themes are considered and addressed throughout the volume:

– | What was the late Mesolithic background against which the Neolithic began in the Irish Sea zone? Were there already hints of a worldview or mindset that might have been amenable to adoption of Neolithic things, including the construction of monuments? |

– | Following on from that, how does a consideration of chambered tombs and landscape articulate with our understanding of the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition? |

– | How does studying the landscape setting of sites enable us to see regional differences or long term trajectories for the development of the Neolithic in different parts of the Irish Sea zone? |

– | What might have been the nature of contact across the Irish Sea zone in the Neolithic? Were people regularly in contact, or just occasionally? Furthermore, how might people on one side of the Irish Sea have conceived of people on the other side? |

– | What does a study of the chambered tombs of the Irish Sea zone in their landscape setting tell us about the Neolithic, but also what are the shortcomings of looking at this type of evidence only? What are the future research questions we should be addressing in this area if we are to further our understanding of the sequence here? |

All of these issues are raised at various points in the volume, and then returned to at the end of the book in chapter 8.

Dates and dating

One of the great frustrations with the data sets considered in this volume is the lack of a good series of dates (see chapter 4). Radiocarbon dates exist, but not in the quantity that one would wish for. Many dates have large deviations which mean they are not particularly useful, and others come from potentially contaminated sources. This is a frustrating situation, but of course one that is paralleled in other parts of the country.

Throughout the volume I refer to different periods in general terms. The bulk of the volume considers evidence from the early Neolithic, defined here are 4000BC–3400 BC. It is this period that sees the construction of what I describe here as the early Neolithic chambered tombs of the Irish Sea zone.

Late Mesolithic c6500 BC–4000 BC

Early Neolithic c4000 BC–3400 BC

(Within this the Earliest Neolithic is c4000 BC–3800)

Middle Neolithic 3400 BC–2900/2800 BC

Late Neolithic 2900/2800 BC–2400 BC

Conclusion

In this first chapter I have introduced the Irish Sea z...