![]()

One

Troubles of an Anthropologist

The Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena

In August 1986, Alice Auma, a young woman from Gulu in Acholi in northern Uganda, began raising an army, which was called the Holy Spirit Mobile Forces (HSMF).1 From a local perspective, she did this on orders from and as the spirit-medium of a Christian holy spirit named Lakwena. Along with this spirit who was the Chairman and Commander in Chief of the movement, other spirits – like Wrong Element from the United States, Ching Po from Korea, Franko from Zaire, some Islamic fighting spirits, and a spirit named Nyaker from Acholi – also took possession of her. These spirits conducted the war. They also provided the other-worldly legitimation for the undertaking.

In a situation of extreme internal and external threat, Alice began waging a war against Evil. This evil manifested itself in a number of ways: first, as an external enemy, represented by the government army, the National Resistance Army (NRA);2 and secondly, as an internal enemy, in the form of impure soldiers, witches, and sorcerers.

In November 1986, Alice moved to Kitgum and took over 150 soldiers from another resistance movement, the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA), which was also fighting the government. In a complex initiation ritual, she purified these soldiers of evil and taught them what she termed the Holy Spirit Tactics, a special method of fighting invented by the spirit Lakwena. She instituted a number of prohibitions, called Holy Spirit Safety Precautions, also ordered by the spirit Lakwena. With these 150 soldiers, at the end of November she began attacking various NRA units stationed in Acholi. Because she was successful and managed to gain the sympathy of a large part of the population even outside Acholi, she was joined not only by soldiers (from other movements), but also by peasants, school and college students, teachers, businessmen, a former government minister, and a number of girls and women.

The HSMF marched from Kitgum to Lira, Soroti, Kumi, Mbale, Tororo, and as far as Jinja, where they were decisively defeated at the end of October 1987. Alice had to flee to Kenya, where she was granted political asylum, and she is alleged to be living in northern Kenya today.

The war in northern Uganda did not come to an end with her defeat, however, for the spirit Lakwena did not give up. He took possession of Alice’s father, who continued fighting with the remaining soldiers of the HSMF until he surrendered to the NRA in 1989. In addition, Lakwena took possession of a young man named Joseph Kony, who continued the war against the NRA up to the present.

Mass Media and Feedback

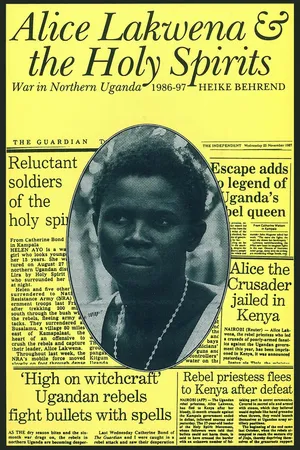

When I began my work, the subject of my research, Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement (HSM), had no place in the books and articles of my colleagues; it had not yet been taken up in scientific discourse. But I did not have the privilege of writing the first text on the movement, for the HSM had already been created by the mass media.

In 1986, when a young woman in Acholi, in northern Uganda, began creating an army on orders from a holy Christian spirit, this was not really noted as an event. Not until she had inflicted severe losses on the government army in several battles, especially the battle at Corner Kilak, and marched on the capital, Kampala, was she seized upon not only by the local but also by the international mass media. The press created the images and stereotypes that would shape discourse on the HSM. In local and international headlines, Alice was designated as a rebel or voodoo priest, a witch, a prophetess, a former prostitute, the future Queen of Uganda, and a Jeanne d’Arc in the Ugandan swamp. Jeanne d’Arc, too, was called a saint and a prophetess and was reviled by her enemies as a prostitute and a witch.) Her movement was depicted as a bizarre, anachronistic, suicidal enterprise in which hordes armed only with stones and sticks were conducting a senseless struggle.

The reporting addressed a topic that will be treated extensively in what follows, namely witchcraft and sorcery. In New Vision, a Ugandan daily paper loyal to the government, Alice was called a witch doctor as early as 21 March 1987. And on 3 April 1987, one could read: ‘The extraordinary casualties rate suffered by the rebels is largely explained by their continuing reliance on witchcraft as a means of primitive mobilisation.’ This was followed by a report that provides a typical example of war propaganda:

Alice murdered a child in a ghastly ritual sacrifice after the second attack on Lira 21 March [1987]. Lakwena found a woman who had twins and took one of them. The child was then killed and its liver eaten by the rebel soldiers. The sacrifice3 was intended to strengthen rebels through witchcraft . . . (New Vision, 3 April 1987).

It is commonplace that charges of witchcraft and cannibalism are among the stereotypes used to designate those to be excluded: the other, strangers, and enemies (cf. Arens 1980). War propaganda in the First and Second World Wars also employed this theme (cf. Fussell, 1977:115ff.).

The Holy Spirit soldiers did not remain uninfluenced by the mass media. They listened regularly to the radio, especially the BBC and Deutsche Welle. They also read newspapers and magazines. They heard and read the reports and reportage on themselves and their struggle. Their own significance was conveyed to them in the media.4 They learned how they were seen by others and attempted to live up to, as well as to contradict, the images drawn of them.

In an interview Alice – or rather, the spirit Lakwena – granted reporters a few days before her defeat at Jinja, she tried to correct the picture the media had sketched of her and her movement. She announced in the Acholi language (which one of her soldiers, Mike Ocan, translated into English) that the spirit Lakwena was fighting to depose the Museveni government and unite all the people in Uganda. She said that the war was also being conducted to remove all wrong elements from the society and to bring peace, and that she was here to proclaim the word of the holy spirit (Sunday Nation, 25 October 1987). In addition, she demanded balanced reporting (Allen, 1991:395).

Alice and the Holy Spirit soldiers were aware of the power of the mass media, and tried to build up a counterforce to meet it by setting up a Department of Information and Publicity within the HSM. It produced leaflets giving information on the goals of the movement, distributed them among the populace, wrote letters to chiefs and politicians, and also collected information. A radio set was available and a photographer took pictures of prisoners of war, visitors, captured weapons, and rituals. The Holy Spirit soldiers wrote their own texts. They kept diaries; the commanders and heads of the Frontline Co-ordination Team (FCT) drew up lists of casualties, recruitments, and gifts from civilians; they kept minutes of meetings and composed reports on the individual battles. And the chief clerk, Alice’s secretary; wrote down what the spirits had to say when they took possession of Alice, their medium. Individual soldiers also noted in school notebooks the twenty Holy Spirit Safety Precautions, rules the spirits imposed on them, as well as prayers and church hymns. And pharmacists, nurses, and paramedics noted the formulas for various medications invented by the spirit Lakwena.

The HSM documented itself and produced its own texts in answer to the mass media. Composing these writings was an act of self-assertion, an attempt to have their truth, their version of the story prevail against others. In a certain sense it was also a magical act with which they fixed a reality that became more real through the very act of writing.

But even the attempt to shed the images and stereotypes of the mass media had to take their power into account. Some of these images remained powerful even in the opposing texts.

Field Research in a War Zone

Ethnography is currently conducted in a world in which the commodities of the Western and Eastern industrial countries – such as Coca-Cola, transister radios, sunglasses, clocks, cars, etc. – are found everywhere, including on the peripheries. And although it appears as if the differences between the various cultures are increasingly being levelled to produce a homogenous world (Kramer, 1987:284), ethnographic works have shown (cf., for example, Taussig, 1980; Appadurai, 1988; Werbner, 1989:68; Comaroff and Comaroff 1990) that the people of the so-called Third World adopt and transform these wares in their own independent way. The commodities develop their own life-history and their own meanings; sometimes they are transformed into status symbols or are integrated in a sacred exchange, thus even losing their character as commodities. Torn from the context of our culture, they confront us again in another context, one which is foreign to us. We think we recognize them as our own, and yet, when we look at them closely, they appear alien or at least alienated.

It is no longer ethnographic comparison that brings the objects of our culture and of other cultures together; rather, they confront us side by side, already brought into a new context in cultures which are foreign to us. Perhaps recognizing familiar things in a foreign context allows us to define more precisely the difference that exists between the meanings which are familiar to us and the new meanings in another context.

Not only goods produced in the West, but also mutual information and knowledge of each other reach the peripheries of our world via the mass media. In this way, the anthropologist and the subjects of his field research are a priori familiar and known at the same time as they are strange to each other (Marcus and Fischer, 1986:112). As already noted, the mass media also affect what we have up to now called ethnographic reality. They deliver pre-formed images to be relived. They create feedback. Ethnographic reality can no longer be assumed to be ‘authentic’; rather, we anthropologists must consider how it is produced – and what models it imitates.

Since centres and peripheries influence each other, we can no longer speak of independent, self-sufficient cultures, which were long the classic analytical units of ethnology (ibid). And thus the dichotomy, so customary in anthropology, between the ‘traditional’ and the ‘modern’ has also lost its validity (cf. Ranger, 1981).

It is already becoming apparent that in future, anthropologists will increasingly be confronted with an (ethnographic) reality that they themselves (together with the subjects of their research) have created. When I talked with Acholi elders in northern Uganda, I could not fail to note that my discussion partners had already read, and were reporting to me from, books and articles that missionaries, anthropologists, and historians had written on their culture and history. Thus I encountered in their answers not so much authentic knowledge as my own colleagues – and, in a sense, myself. I also discovered that a number of local ethnographies and historiographies already existed that had been written by Acholi like Reuben Anywar, Alipayo Latigo, Noah Ochara, Lacito Okech, and R. M. Nono,5 to mention but a few. The texts of Europeans, especially those by missionaries from the Comboni Mission, by Crazzolara on the history of the Lwo (1937), and by Pelligrini on the history and ‘tradition’ of the Acholi (1949) found entry into these indigenous texts. So I had to ask myself whether the Acholi elders were telling me their or our story (cf. Bruner, 1986:148f.) and what that meant for distinguishing the interior (emic) from the exterior (etic) view (ibid). Bruner, who sought an answer to these questions in his research on the Pueblo Indians of the United States, assumes that Pueblo Indians and the anthropologists who write about them share the same discourse.

My position is that both Indian enactment, the story they tell about themselves, and our theory, the story we tell, are transformations of each other; they are retellings of a narrative derived from the discursive practice of our historical era (Foucault 1973), instances of never-ceasing reflexivity. (Bruner, 1986:149).

I agree only with part of this statement. For one thing, Bruner neglects the historical perspective, which is precisely where we can trace how a dominant discourse takes over. For those ethnographed, the subjects of our field research, do not share our discourse from the beginning. They put up resistance to their colonization and ‘invention’ (Mudimbe, 1988) and designed counter-discourses, even if (as will be shown in this study) these finally confirmed the hegemony of the European discourse (cf. Comaroff and Comaroff, 1991:18). But it is precisely the history of the hegemony of our discourse which also makes clear the difference that arises from the often original interpretation of the dominant discourse that the ethnographed come up with. In future, noting this difference as precisely as possible may be the ethnographer’s primary goal.

From the outbreak of the fighting in May and June 1986, northern Uganda became increasingly isolated from the rest of the country. The NRA government declared the Acholi District a war zone. Roadblocks controlled access. Transport and trade collapsed almost completely towards the end of 1987. As early as March, the NRA forced a large part of the population in Acholi to leave their farms and take ‘refuge’ in camps or in the city. But, I was told, many fled less from the so-called ‘rebels’ than from the soldiers of the NRA, who plundered, stole livestock, and burned houses, supplies, and fields.

In November 1989, I was able to visit northern Uganda – Acholi – for the first time. Most of the more than 150,000 refugees the war had created had now returned to their villages and begun to cultivate their fields. Following a government offer of an amnesty and a peace treaty with another resistance movement, the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA), thousands of ‘rebels’ left the bush, returning to their villages or joining the NRA and militias to fight against their former allies. A few bushfighters who refused to surrender joined up with the Holy Spirit soldiers of Joseph Kony. They conducted a guerrilla war, staging ambushes here and there or daring an occasional attack.

The NRA seldom managed to catch Holy Spirit soldiers, and all too often vented their frustration on the local populace. After each defeat, they took vengeance on innocent people. The result was that the population indeed sympathized more or less with the Holy Spirit soldiers, though they too degenerated more and more into marauding bands of thieves.

In November 1989, Gulu, the capital of Acholi District, was a city ‘occupied’ by the NRA. Trucks carrying soldiers and weapons careered down the main street. Soldiers sat in small bars, rode bicycles, or strolled the streets in groups, singing songs. Some had tied chickens they had acquired to the handlebars of their bicycles, carried them in their knapsacks, or strapped them to the counter of the bar while they drank. The traces of the war had not been eliminated. Many houses lining the main street had been destroyed, their facades burned, the pavements torn up, the street signs perforated by bullets and twisted, and the central roundabout, once planted with glowing red bougainvillea, now consisted of nothing but a heap of stones. The scantily covered dead were carried on stretchers through the city followed by weeping relatives. One woman told me there had been too many dead taken by the war and now by AIDS as well.

While the war continued in the territory surrounding Gulu, and distant gunfire could often be heard, in the afternoons, and especially in the evenings, the sound of machine gun fire also emanated from the video halls in town where low-budget American films or karate films from Taiwan staged a reprise of war. These films provided the models avidly imitated by Holy Spirit soldiers and government troops alike. Soldiers I got to know gave themselves names like ‘Suicide’, ‘Karate’, ‘007’, and ‘James Bond’. And a spirit who liked to introduce himself as ‘King Bruce’, after the karate hero Bruce Lee, fought in the Holy Spirit Movement of Joseph Kony.

I did not pitch my tent in the middle of an Acholi village, as Malinowski exhorted, but took up my quarters in what had been a luxury hotel in town. I was advised to do this because I was told that the Holy Spirit soldiers still made the territory around Gulu insecure. Especially at night, ‘rebels’, militiamen, and government soldiers moved about in small groups plundering farms. Since they all wore the same uniforms, one could never be sure who the plunderers were. In the evenings, many people, ...