Thing 1A. The ceremonial regalia of emperor Maxentius during excavation in 2005. Photo courtesy of Clementina Pannella.

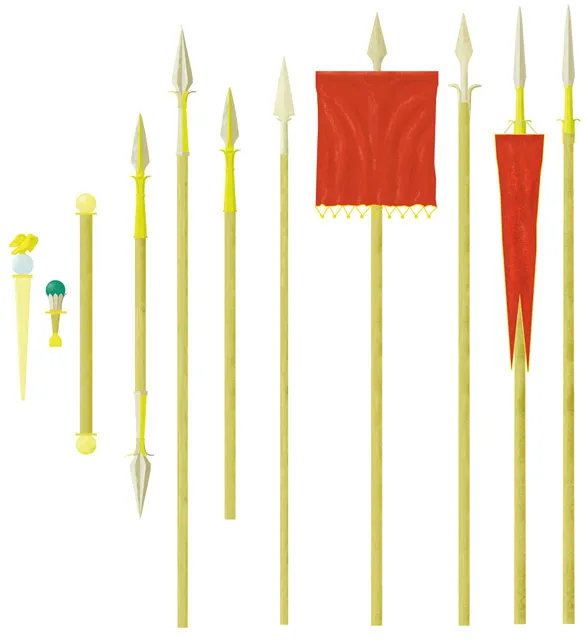

Thing 1C. Ceremonial lance heads in oricalc and iron. Image courtesy of Clementina Pannella.

1. The Ceremonial Regalia of Emperor Maxentius (?)

Rome, early fourth century

Thing 1B. Oricalc and

iron scepter head with glass

sphere. Photo courtesy

of Clementina Pannella.

In July 2005, archaeologists excavating at the base of the Palatine Hill in Rome, just below the palace of the Roman emperors, made the discovery of a lifetime. In the packed-clay floor of a basement room built almost two thousand years ago, they found the ceremonial regalia of a Roman emperor, hastily buried in a hole dug into the floor and never recovered. There were ten objects, three of them scepters of varying shapes and sizes. One featured a gilded green globe cradled in a floral setting of iron and oricalc (a golden-colored alloy of copper and zinc similar to brass); the second was crowned with a large (10 centimeters diameter) sphere of chalcedony, a milky-blue, semiprecious stone; the third apparently consisted of a wooden shaft capped at both ends with globes of greenish glass speckled with gold, of which only the globes remain. Alongside the scepters were two six-bladed spearheads of iron and oricalc, and an assortment of smaller spearheads in iron or a combination of iron and oricalc, most with projecting “winglets” at the base designed for attaching banners and pendants. The objects themselves were apparently wrapped in such banners, judging by the fossilized remains of purplish silk and linen found clinging to most of the items, and then buried inside leather-lined wooden cases.

The dirt used to fill and cover the hole contained a coin of the emperor Diocletian minted in AD 298, as well as shards of pottery datable to around AD 300, placing the moment of the objects’ burial in the early fourth century. During this period, only one emperor lived at Rome who was neither in a position to pass on the symbols of his office to a successor, nor to be buried with them. This was Maxentius, the son of the retired tetrarch Maximian, who ruled over Italy and North Africa between 306 and 312, when he was disastrously defeated and killed by the army of the rival emperor Constantine at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. Probably in the immediate aftermath of the battle, someone close to the defeated emperor took the scepters and other ceremonial insignia from the palace and hastily buried them nearby.

What is perhaps most surprising about the imperial regalia is the relative cheapness of their materials. Oricalc was hardly inexpensive (and a relatively difficult alloy to make), but it was far less costly than gold and even silver; its golden color made it an attractive substitute, evidently, for the real thing. While there are traces of gold leaf probably from the wooden shafts of some of the items, the quantity of precious metals used was minimal, and among the remaining finds only the unusually large Chalcedony sphere was really valuable. The workmanship is highly competent, but certainly nothing unusual by the standards of the age.

In order to understand these objects better, we might try to see them as the product of their particular time and place, and of the changed political circumstances that had prevailed in the Roman Empire since the murder of the last member of the Severan dynasty, Alexander Severus, in 235. Over the ensuing fifty years, we know of nearly fifty individuals who were acclaimed emperor and supported by enough troops to make their claim viable. Many never achieved widespread recognition and were quickly killed, and even most of those recognized as legitimate by their contemporaries also died violently within a few years. The result was near-anarchy: recurring civil wars raged across the empire. Following the return of relative stability with the reign of Diocletian (284–305) and the establishment of the Tetrarchy in 293, there remained four emperors and four separate imperial courts, and further pretenders to the throne. Hence, supplies of resources continued to be strained to the limit, especially the precious metals needed to pay the troops and maintain the infrastructure of the empire.

Yet emperors sought, more than ever, to bolster their tenuous authority by every means possible, including wearing rich costumes and participating in elaborate court ceremonies. When Maxentius was (illegally) proclaimed emperor in 306 by troops loyal to his father, he found himself, like so many others over the preceding seventy-five years, needing to convince all who saw him, and ultimately his rival claimants to power, that he was a “real” emperor. To do so, he needed to act the part.

But since Maxentius was proclaimed in Rome, where no emperors had ruled for decades, suitable imperial regalia may not have been available. In an age when emperors were primarily distinguished by their purple cloaks and crowns, other accoutrements of power such as scepters and standards may simply not have been hoarded or preserved with great care. There is little to suggest that Roman emperors passed down such objects to their successors, or that they became more prized and sought-after with age and the legacy of past owners. Nonetheless, Maxentius needed ceremonial regalia to play his role to the fullest. At a time when precious metals were badly needed to pay the army and fund his grand new public buildings in Rome, he evidently settled on cheaper materials. The best craftsmen in the city were doubtless employed, skilled laborers to be sure, but with no prior experience of making such things.

We might see the finished products as, essentially, props, objects whose value lay in the means of their display and their connection to the person of the emperor, rather than their intrinsic worth. Hence, when Constantine’s troops entered Rome, their main value would have been as trophies, symbols of Maxentius’s defeat. Those loyal to Maxentius buried them instead, to save their ruler a final disgrace.

Further Reading

The only publication of the remarkable 2005 find is C. Panella, ed., I segni di potere. Realtà e immaginario della sovranità nella Roma imperiale (Bari, 2011). S. MacCormack, Art and Ceremony in Late Antiquity (Berkeley, 1981) is a masterful overview of the choreography of power. On the reign of Maxentius and his rapport with the citizens of Rome, M. Cullhed, Conservator urbis suae: Studies in the Politics and Propaganda of the Emperor Maxentius (Stockholm, 1994), is fundamental. J. Curran, Pagan City and Christian Capital (Oxford, 2001), analyzes Rome’s fourth-century transition from a Maxentian to Constantinian city.

Thing 2A. Circus races mosaic pavement from the Villa del Casale, overview. Image courtesy of Enrico Gallocchio/the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

2. Circus Races Mosaic Pavement

Villa del Casale, near Piazza Armerina, Sicily, ca. 300–350

The most popular spectator sport across the Roman Empire was chariot racing, a fast-paced, chaotic, and dangerous mad dash of seven laps around a long, hairpin-shaped track inside a stadium called a circus. The largest and most famous racetrack in the Roman Empire, the Circus Maximus in Rome, was located adjacent to the palace of the Roman emperors on the Palatine Hill. It had a track 580 meters long, with room for more than 100,000 spectators in the stands. (Some estimates put capacity higher still, at 200,000 or more.) Races typically featured chariots with a single driver pulled by a team of four horses, called a quadriga, usually competing in groups of four. At Rome, where chariot racing began at least as early as the sixth century BC, there were four principal teams, known as “factions” and distinguished by their colors: red, white, green and blue, each with many thousands of supporters. By the second and third centuries AD, these factions had become empirewide entertainment corporations, organizing games and spectacles and attracting local supporters in cities across the empire.

Fans of these teams were bitter rivals, and the streets of cities such as Rome, Constantinople, Antioch, and Alexandria were often the scene of bloody clashes between hundreds or even thousands of especially die-hard supporters. (Comparisons to modern soccer hooliganism are in some ways apt, though today’s hooligans are tame in comparison to their late Roman and Byzantine predecessors.) Especially successful charioteers, such as Porphyrius of Constantinople (ca. 500), were the leading celebrities of their day, megastars whose names and images appeared on cups, plates, medallions, children’s toys, and countless other accoutrements of daily life found in households from one end of the Mediterranean to the other.

Some people even decorated their houses with chariot-racing scenes. By the early fourth century, wealthy members of the Roman elite customarily owned one or more large country houses, or villas, furnished with heating systems, bath complexes, and large reception and dining halls, and decorated opulently with marble, paintings, statues, and mosaics. Mosaics were made of tiny cubes of glass or stone, called tesserae, inserted into a mortar backing; multicolored tesserae were often arranged to form decorative patterns or figural imagery, with each individual tessera functioning much like a single pixel in a modern digital screen. Because mosaics were durable, resistant to abrasion and wear, and waterproof, they were especially common on floors. This floor-mosaic depicting chariot-racing scenes was laid around AD 300–350 in a monumental villa at Piazza Armerina, high in the hills of central Sicily. It covers the whole floor of a rectangular vestibule, situated between the residential wing and the bathing complex.

Our mosaic is exceptionally large—23.5 by 5.75 meters, with millions of tesserae!—appropriately since it depicts the Circus Maximus of Rome. At the far right, there is a triangular group of three temples located outside the circus proper. Just to the left appears the curving line of the starting gates, or carceres, with twelve arched bays. In the center of the racetrack, we see the raised divider around which the teams circled, the euripus, its sides sheathed in colored marbles and bristling with statues, with groups of three conical posts (metae) marking the turn at each end. At far left, in the curved end of the stadium (the best seats, where the most accidents occurred), a few spectators appear.

The mosaic actually comprises a composite sequence of four different scenes. At far right, behind the carceres, two charioteers, red and green, prepare for the race; the green driver at left receives his helmet and a whip from an attendant. Moving left, we see the start of the race: the red, white, green, and blue chariots dash from the starting gates and head for the right-hand side of the euripus. Then, midway along the upper straightaway, the scene changes abruptly to show the winning charioteer, his whip-arm raised in celebration. A trumpeter salutes him with a flourish, and a second man waits to hand him a palm frond, the traditional symbol of victory. The other three teams walk slowly behind, the red just behind the green, the blue and white directly beneath them, yet to round the turning post. Finally, at the far (left) end of the track, the chariots are shown in the midst of the race. The white and blue teams, to the left of the obelisk, trail behind the green and red teams, which have already made the turn around the far post onto the bottom straightaway. The red team has just crashed, the driver sprawling face-first into the dirt in a tangle of reins, while the green chariot squeaks past, swerving dangerously.

The size and unusually rich interior décor of the Piazza Armerina villa have led some to suggest that it was built by an emperor, perhaps Maximian or his son, Maxentius. However, it may just as well have been the country residence of a rich Roman senator, the most ambitious of whom continued into the fifth century to fund races in the Circus Maximus as a means of enhancing their family’s prestige and popularity, and achieving high political office for themselves and their offspring.

Such entertainments, which were often accompanied by distributions of food, money, and prizes to the spectators, were one of the few ways in which the ruling class—the empire’s “one percent” who controlled most of its wealth—gave back to the urban masses. They also provided a rare channel for direct communication between rulers and ruled, a venue where an emperor, provincial governor, or other high official could address (via a herald), and actually be heard by, tens of thousands of people, and where those multitudes, chanting in unison, could express their views with relative impunity. Following the model of Rome, the circuses at the cities where the emperors most often resided beginning in the later third century (Trier, Milan, Thessaloniki, Sirmium, Constantinople, Nicomedia, Antioch, perhaps Ravenna) were also placed next to palaces, allowing rulers to proceed directly to their box in the circus. In AD 331, the emperor Constantine even decreed that he be sent transcripts of the chants voiced by crowds in attendance at games and other public...