![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

This is a book about development issues. It asks how development has shown itself over recent decades and what it means to people on the ground. I wish to be sceptical about the term ‘development’ and to recognise that for some it has become a form of religion. I am aware of the dangers of simply carrying on with the assumption that it is unquestionably a good thing even if we cannot really explain precisely what it is. As Swiss scholar Gilbert Rist suggests, we should ‘not yield to ready-made appraisals … [which] take it for granted that “development” exists, that it has a positive value, that it is desirable or even necessary’.1 But it is indeed widely taken for granted that development is necessary – an entire industry of development has grown around the term, encompassing the mission statements, activities and finances of government departments, nongovernmental organisations, charities, international financial institutions, United Nations agencies and transnational companies. As Wolfgang Sachs suggests, development ‘denotes improvement, advance, progress; it signifies something vaguely positive. So it’s difficult to oppose it: who wants to reject the positive?’2

But Mexican activist and intellectual Gustavo Esteva refers to the era of development as the ‘new colonial episode’ and believes that ‘the four decades of development were a huge and irresponsible experiment which, judging by the experience of the majority of the world, has failed miserably’.3 This postdevelopment view supports the argument that development is an unequal and uneven process, and that as such it is an inherently political process. Like the terms globalisation and modernisation, development is predicated on Westernisation. As Hettne states, ‘In order to develop it was deemed necessary for the ‘new nations’ to imitate the Western model – it was a “modernisation imperative”’.4 This modernisation imperative began with US President Harry Truman’s inaugural speech to Congress in 1949, in which he cited large parts of the world as ‘underdeveloped’. So saying, he set off the race for development among Third World nations.

That process of Westernisation, or globalisation, pursued first a rather simplistic form of capitalism, in which development was more or less coincidental with industrialisation and all its attendant processes of technological advancement. The benefits of this process were supposed to trickle down to the poor majority and lift them out of their underdevelopment; but as Joseph Stiglitz (former chief economist at the World Bank) argues, the trickle-down mechanism ‘was never much more than just a belief, an article of faith’.5

As it happened, Western companies (predominantly those of North America and Western Europe) benefited most from this post-war race for development through their already relatively advanced technology. To advance further they needed raw materials and natural resources, found in abundance in Third World countries. To get access to those resources they required an infrastructure adequate to their techniques of production and distribution. To upgrade the infrastructure in Third World countries to an appropriate level loans were required, and these came from the international financial institutions (appropriately referred to as IFIs) established at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944 – the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and their offshoots such as the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). Bilateral loans from government to government and private loans also played a role in this process. Who better to carry out these infrastructural works than the Western companies which already had the technological capacity to do so? The results effectively involved a take-over of Third World natural resources, infrastructure and production by Western companies.

The loans for these developments were made to Third World governments so that they could pay the Western companies for these works, and the results included the Third World debt crisis. This crisis reached a peak of public awareness in the 1980s and early 1990s, but has since slipped off the Western public’s agenda. That does not mean that it has been resolved; far from it – many Third World countries are now permanently and unsustainably in debt to the IFIs. There are those who would argue that this was precisely the intention of the age of ‘development’ – Western capitalist domination and access to the natural resources of the rest of the world.6

Whether that was the deliberate intention or not, we need to ask whether the development intended has occurred for those who Truman identified as underdeveloped. Esteva suggests that despite its promises of widespread enrichment, development ‘for the great majority, has always signified the modernisation of poverty: the growing dependence on the direction and management of others’.7 Ivan Illich refers to ‘development as planned poverty’, and André Gunder Frank refers to, ‘the development of underdevelopment’.8

This perspective describes the theory of dependency which is best understood as a riposte to the free-market economics approach to economic development and international trade. Dependency theory sought to demonstrate how and why these relationships are highly unequal. The theory argues that Western capitalist countries have grown as a result of the expropriation of surpluses from the Third World, especially because of the reliance of Third World countries on export-oriented industries (coffee, bananas, gold and so on) which are precarious in terms of world market prices. The theory uses the notion of core–periphery relationships to highlight the unequal relationship, where the core is the locus of economic power within a global economy.

The most widely cited of the dependency theorists, André Gunder Frank,9 takes matters one step further with his notion of the ‘development of underdevelopment’, which stresses that it is the underdevelopment of the structures in Third World countries created by First World capitalist development that creates dependency. Above all, theories of dependency are in general agreement that the interdependence resulting from global economic expansion suppresses autonomous growth, resulting in unequal and uneven development.

Many development-related non-governmental organisations (NGOs) repeat this message, using evidence from their projects with partner organisations in Third World countries; and if the publicity material of such organisations is a part of your regular diet of information it is difficult not to become seriously concerned about the notion of development as well as the general state of world development. I should make it clear from the outset of this work, however, that, despite what you have read above, I am not against development per se. I have been involved in what is commonly called development work for the last three decades and, like many others so involved, I see it as representing some form of progress and improvement in the quality of life for many people. Experience in Central America, however, has made me aware of the failings and abuses of development, and of the way in which it is used as a theoretical construct to justify prevailing Western ideology.

The region chosen for this portrait of the difference between the theory and practice of development is that of Central America, and the following chapters examine some of the significant and topical activities which have emerged as major issues of contention and concern relating to the benefits of development. A few indicators relating to the ‘development of development’ in Central America are given below as an initial assessment of the region’s level of development.

Whilst there is a definite regional focus on Central America, the development issues covered here are no less relevant to other Third World regions which suffer the same factors holding back their development. Indeed, it can be reasonably argued that certain parts of the African continent are emerging from a particularly violent period of their history, as did most of Central America around two decades ago, and that these African nations are highly likely to serve as the next test bed for the imposition of economic policies from the West. They can therefore learn from the last 20 years of experiences of the Central American nations.

Measuring Development

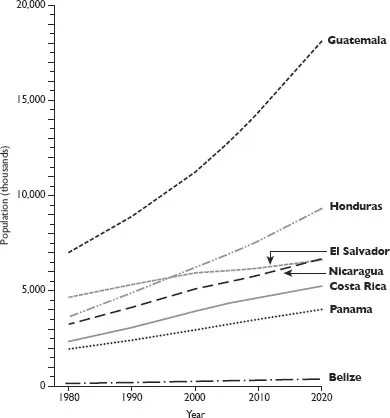

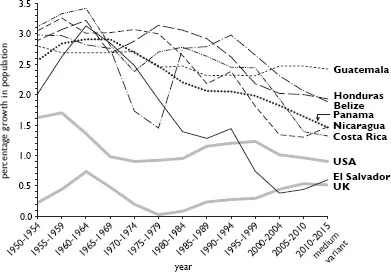

Figures 1.1 and 1.2 show population data and population growth for the Central American countries and the region as a whole, along with comparisons from the UK and USA. These data serve here merely as a point of reference for the tables and figures which follow, and which relate to issues and measures of development. As with definitions of development, there is considerable debate over measures of development. For many years, how far a country had progressed along the generally accepted line of Western development was measured in terms of its per capita gross domestic product (GDP), whose definition is given in Box 1.1. It is still measured in these terms, but the need to use other indicators in order to broaden our understanding of the term ‘development’, and to acknowledge that there is more to development than can be counted in currency, has become accepted even by the World Bank, which provides annual estimates of GDP.

The decade of the 1990s saw an increasing awareness of the need to incorporate human welfare, human rights and poverty reduction into the measurement of development.10 Hence the creation of the Human Development Index (HDI) and later the Human Poverty Index (HPI), compiled by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). In 1990 the UNDP published its first Human Development Report, which included its first calculation of HDI as a composite measure of life expectancy, literacy and per capita income.11 The composite measure is intended to reflect a general sense of wellbeing that people may or may not feel in their lives. The HPI was added later by the UNDP and reflects levels of deprivation in a country through the same variables used in the calculation of the HDI. (The specific definitions of HDI and HPI are also given in Box 1.1.)

Figure 1.1Central American Populations

Source: UN DESA (2009) ‘World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision’, New York: Department for Economic and Social Affairs.

Quite apart from differing definitions of development, a separate book would be required to examine thoroughly all the different assumptions, perspectives and indicators of development and their interpretations. This introductory chapter simply presents a summary portrait of the development levels of Central American countries through a selection of indicators. These are shown in Figure 1.3, which gives comparative data for the UK and USA in several of the charts. As can be seen in Figure 1.3, there is a general level of development in Central America as a whole (in comparison with two of the leading capitalist nations), and a number of significant differences between the seven regional nations.

Figure 1.2Population Growth Rates, Central America

Source: UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division,‘World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision’, New York: DESA. 2009.

Detailed comments about each of the graphs included in Figure 1.3 are not given here. The thesis of the book refers more to how these countries have reached their current levels of development or underdevelopment rather than to a spuriously precise description of those levels. Nevertheless, it would be wrong not to draw the reader’s attention to a number of significant points.

First, by various indicators the countries of Costa Rica and Panama stand above the rest of the region. In the case of Costa Rica, many commentators ascribe this higher level of development to the fact that in 1949 it abolished its army and initiated relatively ambitious programmes of social welfare, health care and education. This may indeed have been a factor in the country’s development, but it is noteworthy that nearly a quarter of its population still lives below the poverty level. Moreover, the US has done all it can to militarise Costa Rica, first in the 1980s as it tried to develop a southern front in its war against the Sandinista government of Nicaragua, and secondly, in 2010 in its agreement with the Costa Rican government to station over 6,000 US troops and part of its naval force in Costa Rican waters in its war on drug trafficking (see Chapter 9).

In the case of Panama, the higher indicators might be explained by the strong US influence over the Panama Canal Zone until the end of the twentieth century. The two-tier society created through US control of the canal zone skewed the distribution of wealth within the country, leading to greater inequality than in other Central American countries. This is most easily observable in Panama City where there is a chasm between the wealth associated with work in the canal zone and the scores of international banks on the one hand and the rest of the Panamanian population on the other.

The second feature of Figure 1.3 which stands out is the consistent difference of scale between the Central American nations and the USA and UK. There is a significant quantitative difference in the richness of life experienced in these two groups of countries. I accept Vandana Shiva’s point that there is a distinction between poverty as subsistence and misery through scarcity and want,12 but it is highly likely that for the majority of the region’s poor this quantitative difference in the richness of life is also felt qualitatively.

A third point of relevance here is the failure of most of these statistics to show the level of inequality within each country. Inequality is important because it negates progress in poverty reduction, erodes the efficient functioning of government institutions and public services, leading people to lose faith in their participation in society. Referring to the second half of the twentieth century, Dirk Kruijt describes the Central American economies as ‘characterised by a stark contrast between a small number of the very rich and masses of the desperately poor ...