1

Tax Evasion and Avoidance

Modern corporations are not independent of the state, but intricately connected with it in many ways. Yet our political leaders generally behave subserviently to businesses bosses, so that corporate power dominates political power. Much of this results from manipulation of the corporate form itself. Nowhere is this seen more clearly than in relation to taxation.

The revenues lost through tax avoidance, including those relating to corporate practices, are hard to estimate, but the European Union claims ‘the level of tax evasion and avoidance in Europe to be around €1 trillion [£830 billion or US$1.25 trillion]’,1 equivalent to 7–8 per cent of the gross domestic product (GDP) of all EU member states. The US Treasury has estimated its tax gap (tax avoidance, evasion and arrears) to be $385 billion.2 A large number of corporations, including Amazon, Apple, eBay, Facebook, Google, Microsoft and Starbucks, have been on the radar of parliamentary committees for avoiding taxes through complex organisational structures.3 The amounts are a stark reminder of how tax avoidance forms an integral part of corporate profitability.

It is sometimes argued that companies should not be taxed at all, since taxes are a cost which they pass on to their customers. This rests on the mistaken view that a company is no more than a bundle of contracts. In reality, a company is a form of property protected by the state. The privilege – it should not be regarded as a right – of incorporation gives shareholders the protection of limited liability, justified by the advantages of enabling the combination of factors of production for large-scale economic activities. This protection enables companies to reap super-profits from economies of scale and scope, and to accumulate large concentrations of capital. Unless their profits are taxed, they will grow even bigger, further distorting competition. Furthermore, if companies were not taxed, the corporate form could easily be used to shelter all kinds of income from taxation.

Behind a wall of secrecy corporations are able to devise complex schemes to boost their profits and meet incessant stock market pressures to report higher profits. Tax avoidance also personally benefits business executives because their remuneration and status is often related to reported profits. In these tasks, corporations are advised and guided by an established tax avoidance industry fronted by accountancy firms, lawyers and financial services experts.4 The system sustains a vast army of professionals engaged in both avoidance and evasion not only of tax but also banking and financial and other forms of regulation, resulting in enormously wasteful expenditures for both firms and governments.

In a globalised world, the distinctions between domestic and global are blurred, and almost all big companies are able to play the tax avoidance games. A few examples will help to illustrate the issues

Corporate Tax Trickery

Within major corporations, the taxation department/division often acts as a profit centre. It is assigned profit and revenue generation targets, and the promotion and the salary increments of its members often depend on meeting the targets. The promotion of tax avoidance schemes by a highly profitable division within Barclays Bank is a telling example, which unusually led to a public rebuke from the government. This rebuke might have curbed two tax avoidance schemes but does not deal with the corporate love affair for tax avoidance or tax havens. A 2013 report published by Action-Aid, summarised in Box 1.1, chastised Barclays for promoting investment in Africa through tax havens, all with the aim of increasing corporate profits and depriving millions of people of much-needed education, healthcare and social infrastructure.5

It is not just financial institutions: other corporations can also arrange their financial affairs in ways that avoid taxes. Companies can use their ownership structures to effectively shift profits and avoid taxes. A good example of this, as shown in Box 1.2, is the strategy adopted by a US private equity firm to enable it to capture and relocate the finances of Boots the Chemists, a major pharmacy chain in the United Kingdom, and to save around £1 billion in tax.

Corporate tax avoidance is not just a problem in the United Kingdom, but an issue wherever the corporate form has taken hold. US companies like Enron and WorldCom used offshore havens and artificial royalty programmes and management fees to reduce taxable profits.6 The Chinese government claims that ‘Tax evasion through transfer pricing accounts for 60 percent of total tax evasion by multinational companies’.7 A Chinese government official added that ‘almost 90 per cent of the foreign enterprises are making money under the table. … most commonly, they use transfer pricing to dodge tax payments.8 A former senior fellow of the Brookings Institution has argued that transfer pricing is used by virtually every multinational corporation to shift profits at will around the globe.12 So in the next section we look at the root cause of the ease with which companies are able to shift profits and avoid taxes.

Box 1.1 Tax avoidance promotion by Barclays Bank

Barclays Bank, a UK-based major international financial institution, came under public scrutiny because of the mismatch between its profits and taxes. For the years 2010–12, Barclays reported pre-tax profits of £5.7 billion, £3.2 billion and £4.8 billion respectively, but paid UK corporation tax of £147 million in 2010, £296 million in 2011 and £82 million in 2012.9 One of the reasons for the mismatch between profits and tax is the existence of its tax division, which generated revenues of more than £1 billion a year between 2007 and 2010. One of its roles was to craft tax avoidance schemes. In 2012, the UK government took the rather unusual step of blocking two tax avoidance schemes which could have enabled Barclays and/or its clients to avoid around £500 million of UK corporate tax.10 A Treasury press release referred to both schemes as ‘highly abusive’ and ‘designed to work around legislation that has been introduced in the past to block similar attempts at tax avoidance’.11 The first scheme was designed to ensure that the commercial profit arising to the bank from a buyback of its own debt would escape corporation tax. The second scheme involved the use of authorised investment funds (AIFs), and sought to convert non-taxable income into an amount carrying a repayable tax credit in an attempt to secure ‘repayment’ from the Exchequer of tax that has not been paid.

International tax avoidance by multinational or transnational corporations (TNCs)13 exploits the tax haven and ‘offshore’ secrecy system, which was originally devised by and for them. However, tax havens are now also used for all kinds of evasion, not only of taxes, but of other laws, facilitating money-laundering for public and private corruption, terrorism, and other criminal activities. The offshore system has particularly distorted the finance sector, as an element in shadow banking and other techniques which contributed to the excessive leverage, helping to feed the bubble which caused the financial crash of 2007–09.

Box 1.2 The takeover and detaxing of Boots the Chemists

Boots was set up in Nottingham in the United Kingdom in 1849, and in July 2006, after a merger with Alliance Unichem plc, it became known as Alliance Boots. In 2007, the merged entity became the subject of the largest-ever leveraged buyout, led by the US private equity firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. LP (KKR). KKR acquired Alliance Boots for about £12 billion through its holding company in Gibraltar. The company continued to trade in the United Kingdom with the same brand name but was reincorporated in the low-tax canton of Zug in Switzerland. KKR holds its stake in Alliance Boots through various funds and finance companies located in the Cayman Islands and Luxembourg.

The acquisition was funded by a debt of £9 billion, and most of it has been left on the balance sheet of the UK operations. This potentially enables the company to write off the interest payments against profits even though profitable activities are carried out in other places, often low-tax jurisdictions. Alliance Boots operates in 25 countries and has an annual turnover of £22 billion. It has virtually no revenues in Zug and about 68 per cent of its trading profits come from the United Kingdom. The leveraged buyout and the loading of debt to the United Kingdom enabled the company to virtually eliminate its corporate tax liability in the United Kingdom in 2008. A report published by War on Want and UNITE states that the uneven allocation of the debt and the resulting tax relief on interest payments has enabled Alliance Boots to reduce its taxable income by some £4.2 billion for the six years to 2013. This has reduced the company’s UK tax bill by between £1.12 to £1.28 billion.14

Outdated Principles in International Tax Law

These problems result from a deep structural flaw in the international tax system. This flaw is the failure to treat multinationals according to the economic reality that they operate as integrated firms under central direction.15 Instead, a principle has become gradually entrenched that they should be taxed as if they were separate enterprises in each country dealing independently with each other. This can be referred to as the Separate Enterprise – Arm’s Length Principle (SE-ALP). For example, FTSE100 companies have 34,216 subsidiary companies, joint ventures and associates, including 8,492 in tax havens that levy little or no tax on corporate profits.16 Under the current practices, they are all treated as separate taxable entities even though they have common shareholders, boards of directors, strategy, logos and websites. This not only allows but encourages multinationals to organise their affairs by forming entities in suitable jurisdictions to reduce their overall effective tax rate by a variety of means.

Companies say that they only obey the rules decided by governments. But this is disingenuous. Business advisers and lobbyists are also heavily involved in designing the rules. Perhaps even more importantly, they are also central to moulding how the system works in practice, through the mutual understandings of business representatives and regulators. These technical specialists form a closed community of interpretation, reinforced by the movement of individuals from government service to working as business advisers – and less often in the other direction.

International tax treaty provisions are still based on models drawn up under the League of Nations in 1928, when international investment consisted mainly of loans.17 The treaty models gave the state of residence of the investor the primary right to tax the income from investment (interest, dividends, fees and royalties), while the host country where the business was located could tax its profits. Some multinationals had emerged by the 1920s, and the rules were adapted for them, by requiring branches and affiliates in different countries to be treated as if they were independent entities dealing at arm’s length. However, to prevent ‘diversion’ of profits, the treaty models provided that tax authorities could adjust their accounts, and national laws gave them powers generally to ensure that the levels of profit of branches or subsidiaries of foreign firms were similar to those of local competitors, or a fair reflection of their contribution to the firm as a whole.

Locating Offshore and Profit Shifting

The multinationals that developed in the last half-century are very different. As business organisations they are highly integrated and centrally directed, but in legal form they consist of often hundreds of different affiliates. In the past few decades tax-driven corporate restructuring has mushroomed, using complex structures designed to take advantage of national tax rules, especially regarding where a company is considered to be resident, and where the sources of its income are. In simplified terms, three stages and types of structure can be identified.

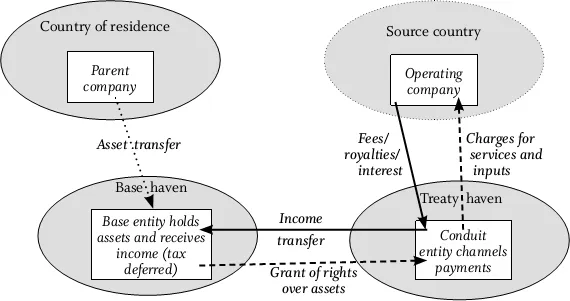

Figure 1.1 Basic tax avoidance strategies

First, and most basic, is a ‘stepping stone’ arrangement (see Figure 1.1). An operating affiliate in a source country can make payments of fees for services such as headquarters management, royalties for intellectual property rights (IPR), and interest on loans, all of which are allowed to be deducted to reduce its taxable business profits. These payments flow to one or more affiliated holding companies, in a country with suitable tax treaties, such as the Netherlands, Switzerland or Singapore, so they will be subject to no or low withholding taxes. The bulk of the income is passed through this conduit, leaving it with a nominal level of profit, to a ‘base’ affiliate in a classical tax haven, such as Bermuda or the Cayman Islands, which does not tax such profits. This ensures low effective tax rates for the firm’s foreign earnings, if they do not need to be repatriated to finance dividends to shareholders. They can be retained for reinvestment by making loans to the firm’s affiliates, even to the parent, which also means that the interest can be deducted from income.

This ability to finance expansion through lightly taxed retained earnings has long been a major competitive advantage for multinationals. Next, they began to reorganise their operations to exploit tax advantages offered by states. In the 1990s, competition to attract inward investment led many countries to provide tax holidays, which were attractive especially for mobile businesses.18 For example, computer chip manufacturer Intel opened major manufacturing facilities in Puerto Rico, Malaysia, the Philippines, Ireland and Israel, all of which offered tax holidays.19 This type of avoidance was harder to combat than the basic ‘stepping stone’ arrangement, because these affiliates were not mere letter-box companies receiving only ‘passive income’, which is a key criterion in national laws on ‘controlled foreign corporations’ (CFCs) enacted by the United States and a number of other countries to combat tax avoidance. It is difficult to treat such an affiliate as a CFC so as to make its income directly taxable as attributable to its parent because it is engaged in active business.20 Multinationals have, of course, also lobbied to limit the scope of the passive business definitions, so that many financial services activities have been excluded. Consequently, the profits of hedge funds and private equity firms can be treated as arising in zero-tax countries, such as the Cayman Islands, simply because their transactions are booked by an affiliate there, even though the investment decisi...