![]()

Part I

Art World

![]()

Introduction I:

Welcome to Our Art World

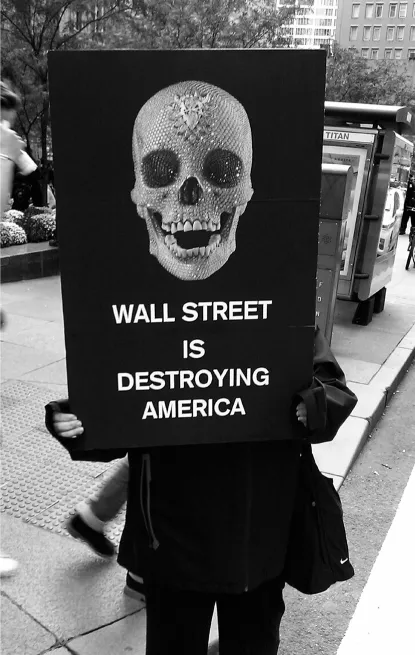

Figure 4 Protester with Damien Hirst sign during the first week of Occupy Wall Street, September, 2011

(Image Chris Kasper, 2011)

Having died twice, the artist is neither modern nor postmodern, yet caught in the order of time conditioned by her relation to the symptom, her relation to the art world.

Marc James Léger1

How does the growing embrace of socially engaged art practice by mainstream culture relate to unprecedented fiscal indebtedness among students and artists? And what do we make of provocative claims that Occupy Wall Street was in fact a contemporary art project? Part I examines these entwined issues through the common denominator of our art world, a term difficult to define, yet ubiquitous in use. For people directly involved in it, the art world is a familiar space (or system, or economy) that stands apart from the so-called real world and yet is also increasingly entangled with the real world (which curiously appears less and less real itself of late). This introduction argues that the art world must be analyzed as a “totality” whose features are simultaneously more exposed and less exceptional thanks to the broader crisis of deregulated capitalism and erosion of liberal democracy at the start of the twenty-first century.

City of God

One phrase, the art world, appears throughout this book with great frequency and for two reasons above all. First, it designates a field of cultural practice and, second, it delimits my chosen area of critical enquiry. Most often the expression is used in commonsensical way, appearing with adjectives such as “contemporary,” “mainstream,” “institutional,” or “elite” preceding it. It was not until after my early essays were completed that I further qualified what the art world actually means analytically. In 2007 I wrote: “By the term art world I mean the integrated, trans-national economy of auction houses, dealers, collectors, international biennials, and trade publications that, together with curators, artists and critics, reproduce the market, as well as the discourse that influences the appreciation and demand for highly valuable artworks.”2

Two features of this definition color my subsequent research into contemporary art. First, is the implied lack of impartiality evident from the definition’s focus on the art world as a set of business relations within a capitalist marketplace. No doubt this bias has its roots in my own development as an artist, writer and activist lending all my writings a partisan, anti-capitalist tendency. Likewise, most of my writings engage with the absence/presence of a countervailing sphere of invisible or overlooked art production and its history, a missing mass that makes the art world possible in the first place. Thus, my point of view has primarily been one of constantly looking up, from down below, or looking in perhaps from a marginalized but parallel dimension of artistic dark matter. The second contention made here is that the art world is an integrated system of production, and not, as some postmodernist critics contend, merely a bundle of overlapping practices, discourses or subcultures with varying degrees of autonomy, connectivity and interdependence. For even though the art world may appear piecemeal, it is, as is capitalism, a totality that is typically visible only as localized phenomena or in a fragment, which is, in Adorno’s terms, “that part of the totality of the work that opposes totality.”3 Or, to place a bit of spin on a maxim by György Lukács, despite its fragmented semblance our art world is an objective totality of delirious social relations.4

To clarify this point, it is helpful to consider a famous definition of the art world, made by the philosopher Arthur Danto in a celebrated meditation on Warhol’s Brillo Boxes. As Danto put it, “the art world stands to the real world as the City of God stands to the Earthly city.” In order to gain admission, Warhol’s Brillo Boxes required an indiscernible difference to mark them out from other mass-produced commodities (although Warhol’s boxes were, in fact, built from wood and silk-screened, an issue that Danto overlooked). Danto’s solution is devastatingly simple: “To see something as art requires something the eye cannot descry—an atmosphere of artistic theory, a knowledge of the history of art: an art world.”5

This definition of the art world is very well known, but its full implications are rarely discussed. In the opening stages of his thought experiment, Danto introduces “Testadura,” the “philistine” who cannot see the artwork, just another object. It is helpful sometimes to remember that very few people are born speaking art theory, or reeling off the lineage of contemporary art. That is to say, we are all “philistines” at some point. It is art education that shows artists the City of God, though it doesn’t let them through the gates. Instead, perhaps, it reveals the art that seems now to be everywhere: in the underwhelming objects, in gatherings, even perhaps in an Occupy Wall Street (OWS) protest. Stranger still, this art has been stripped bare, first via a long process of artists questioning the power relations that inhabit the theories that they inherit and, second, by the myth-melting processes of capital. To understand these contradictions, it is necessary to view the art world with Testadura’s bluntness as I do, from “below.” The key axis of Part I, therefore, is between the art school, where everything is learned, and the museum, where initiates forget they ever had to learn anything as they perform the rituals of art.6

Danto’s Artworld thesis appeared in 1964, and since then these cultural rituals have been integrated into those of capitalism. As architectural historian David Joselit recently suggested, a new wave of museum construction seems to “function as the art world’s central banks.” Designed for cities “around the world by star architects like Frank Gehry, Renzo Piano, Jacques Herzog, and Pierre de Meuron”: “in a time of economic instability, precipitated by worldwide financial failures since 2008, people now see art as an international currency. Art is a fungible hedge [that] must cross borders as easily as the dollar, the euro, the yen, and the renminbi.”7

Perhaps it was Haacke’s real estate mappings, real-time projects and critical provenance tracings of Monet and Seurat paintings in the early 1970s that first indicated all that what was once so solid, including works of art, were beginning to melt into thin air. “There is nothing so edifying,” writes W.J.T. Mitchell, “as the moral shock of capitalist cultural institutions when they look at their own faces in the mirror.”8 And along with notions of cultural privilege the idea of artistic autonomy was also dissolving. Since then, these moments of breakdown and demystification have only accelerated. To this assault was added museum interventions by Art Workers’ Coalition and the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, artistic deconstructions by Daniel Buren and Michael Asher, the cultural utilitarianism of Artists Placement Group, theories of institutional critique from Art & Language, museum maintenance performances by Mierle Laderman Ukeles, and the dematerialization of art world privilege via Lucy R. Lippard’s copious writings. A bit later on came the critical practices of Martha Rosler, Carol Condé and Karl Beveridge, Mary Kelly, Alan Sekula, Fred Lonidier, Conrad Atkinson, Artists Meeting for Cultural Change (AMCC), Art Against Apartheid, the militant art journals Red-Herring and The Fox, and still further on Political Art Documentation/Distribution (PAD/D), Black Audio Film Collective (UK), Group Material, followed by John Malpede’s LAPD (Los Angeles Poverty Department), Bullet Space, Artists Meeting Against US Intervention in Central America, Guerrilla Girls, and Gran Fury, so that by the end of the Cold War a process was unfolding whereby the previously unseen (I do not mean unseen as in unseeable, but instead intentionally unseen) conditions of cultural labor began to be foregrounded. All of this was paralleled by the rise of a social history of art in the US and the UK starting in the 1970s with figures such as T.J. Clark, Carol Duncan, Linda Nochlin, Frances K. Pohl, Andrew Hemingway, Alan Wallach, Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock.

Rather than “new,” as the “avant-garde” is often defined, this self-critical artistic work represented a disenchanted revelation of the power that sustains the art world. At the same time, these moments of resistance were spurred along by changes in the working conditions of art as capital subsumed artistic practices into its own forces of production. On the one hand, art has been stripped bare by critical artists who have labored to reveal the workings of power within it. On the other, the speculative incursions of oligarchs who want to put the “City of God” to work as a kind of eternalized asset class have turned autonomous art into an unregulated investment market. And here we arrive at this book’s central observation. Culture’s internal aesthetic character is now manifest as so many flagrant, unconcealed and utterly ordinary attributes, so many data points, so that the desire by 1960s artists to transform their elite social position into that of a “cultural worker” has finally been fulfilled. Today artists are simply another worker, no more or less. We might best describe this new mise en scène as simply bare art.

Ironically, the activities of critical artists have been assisted by capital’s own hegemonic reach, in which it “mobilizes to its advantage all the attitudes characterizing our species, putting to work life as such,” explains Paolo Virno, or as Jameson explains following Marx, capital is “the first transparent society, that is to say, the first social formation in which the ‘secret of production’ is revealed.”9 The “secret” of artistic production is also revealed to be social production, a disclosure that has occurred as the pursuit of surplus value comes to dominate all fields of human activity. Like a hallowed covenant we reluctantly pledge ourselves to follow, there is little time or need now for older, ideological facades and cover stories. Claustrophobic, tautological, our bare art world is our bare art world is our bare art world. It emerges in successive and accelerating states of shadowless economic exposure following capital’s ever-quickening swerves from crisis to crisis—the oil crisis and stagflated 1970s, the Savings & Loan meltdown 1980s/1990s, the dotcom bust 2000s, Argentinian default at about the same time, and of course the “Great Recession” starting late in 2007 with 8.7 million lost jobs between 2008 and 2010. But this does not mean all artists like it. As Caroline Woolard of BFAMFAPhD asked with added incredulity, “what is a work of art in the age of $120,000 art degrees?”10

Clearly a growing number of previously invisible cultural producers have begun to see themselves as a category in and for themselves as the social nature of art is unavoidably made visible. Like some weird redundant agency, this no-longer dark matter is commonplace—the art fabricators, handlers, installers whose own art practice always takes a back seat—and simultaneously bristling with a profound potential for positive change as well as an unpredictable and deep-seated sense of resentment. Tuition-indebted artist and co-founder of Occupy Museums Noah Fischer sums up the situation with frustration: “The contemporary art market is one of the largest deregulated transaction platforms in the world—a space where Russian oligarchs launder money, real estate tycoons decorate private museums for tax benefits, and celebrities of fashion, screen, and music trade cash for credibility.”11

Pushing Back

Capitalist communication networks serve to quicken and thicken these resistant formations so that groups such as WAGE (Working Artists and the Greater Economy), Occupy Museums, Gulf Labor, Debtfair, Arts & Labor, MTL (Nitasha Dhillon and Amin Husain), Decolonize This Place and BFAMFAPhD, among others, openly acknowledged that they are indeed an art labor force whose work should not simply benefit the 1% of the art world’s global superstars and mega-galleries. Speaking as artist and organizer of WAGE, Lise Soskolne bluntly lays out the view of a bare art world from below:

Even though it is made up of a for-profit and a non-profit sector, the world of art is an industry just like any other. All of its supporting institutions, including philanthropy, contribute to its perpetuation and growth as such, and all those who contribute to its economy by facilitating the production and distribution of art products, including and especially artists, are wholly unexceptional in their support for and exploitation by it. The role of art and artists within this multibillion-dollar industry is to serve capital—just like everyone else.12

While some artists organize for better “working conditions,” others parody enterprise culture, cunningly montaging the leftovers of a broken society into “mock institutions”: DIY organizations that sometimes work as well as or better than the bankrupt institutions their founders initially sought to mimic. Debtfair derides the concept of the Art Fair by offering an open invitation to all artists in Houston, Texas, to submit work while also relaying their level of student debt: “Total debts amongst the artists are tabulated in a running tally while identifying the institutions in which these debts are rooted, [thus] while many feel isolated by their economic reality, Debtfair works to build solidarity and community around our shared economic conditions.”13

At this point, we must pause to consider how these forces of resistance actually exist within an art world that is so intimately tied to the interests of the 1%. And consequently, does the past, present and anticipated future defeat of artistic opposition just return us to the age-old complaint...