eBook - ePub

Deep Cultural Diversity

Gilles Paquet

This is a test

Share book

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Deep Cultural Diversity

Gilles Paquet

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Political commentator and public policy analyst Gilles Paquet examines the benefits and drawbacks of Canada's multiculturalism policy. He rejects the current policy which perpetuates difference and articulates a model for Canadian transculturalism, a more fluid understanding of multiculturalism based on the philosophy of cosmopolitanism which would strengthen moral contracts and encourage the social engagement of all Canadians.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Deep Cultural Diversity an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Deep Cultural Diversity by Gilles Paquet in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Política cultural. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Analyzing Diversity

1

The Problematique of Cultural Pluralism

From the dew of the few flakes that melt on our faces we cannot reconstruct the snowstorm.—John Updike

Betting on diversity is a moral and political act. It is “the celebration of human possibilities.” This position is based on the beliefs that the best way in which individuals can make a good life for themselves is to have a plurality of values at their disposal; that cultural plurality is an asset; and that it is the role of the state to create the conditions in which diversity can blossom (Kekes 1993). However, this entails the necessity of imposing limits, for not all possibilities are reasonable. Differences breed not only social learning but conflicts. Particular identities rooted in cultural differences may generate tension. The challenges are to build new forms of identity that are likely to be workable, and to promote coexistence and cooperation in an increasingly pluralistic and interdependent world.

Promoting common citizenship and a sense of belonging in contexts where a mosaic of deeply different cultures and identities prevail is often mentioned as the panacea. This is more easily stated that done. This world of diversity is plagued with problems that prevent understanding and consensus. Both a loose problematique and a preliminary lexicon might provide ways to feed an intelligent conversation on these issues.

A Loose Problematique

Plurality is a general recognition that diversity is a new reality in modern societies and is the bedrock on which “modern culture” must be built. Yet these three words can be frustratingly opaque. What is “culture”? What is “diversity”? What is “plurality”?

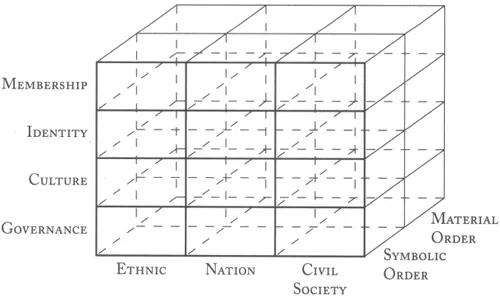

The role of a problematique and of a lexicon is not to provide answers but rather to generate a toolbox that will permit the formulation of relevant questions. Without a framework and a clear vocabulary, or, at least, a clear view of the confused nature of the vocabulary in good currency, one cannot conduct a useful conversation. To help us map the territory, we have identified three major dimensions in a classificatory scheme, as presented in Figure 2.

The first dimension pertains to the dichotomy between material and symbolic orders. This notion has emerged clearly from the works of Raymond Breton, among others, and has contributed to a broadening of the debate on culture in Canada (Breton 1984). The insistence on the importance of the symbolic order allowed the discussion to escape from the traps of traditional analyses of interest groups’ demands for material or financial gratifications, and to focus equally on problems of collective identity (traditions, customs, norms, and so on) that are embedded in the forms and styles of private and public institutions. It has reaffirmed something that is often forgotten: that the symbolic order underpins the workings of the material order and is also a prime target of government interventions (Tussman 1977).

Figure 2. The Main Dimensions of Cultural Pluralism

For Breton and others the construction of the symbolic order is as important as the construction of the material socioeconomy. Citizens traditionally have sought a certain concordance between their private way of life (their “culture”) and the style of their public environment (their “national identity”). Their demands for status (recognition within the public space) will often be as vociferous as their demands for access to a good life. Governments of plural democracies must be increasingly involved in monitoring and understanding the symbolic order, both in response to demands by diverse groups, and as a way to temper the potentially destructive behaviour of different and often hostile groups by acting on their representations and perceptions. These more inclusive analyses have helped in providing interpretations built on acknowledging a shift of emphasis from “material” to “symbolic” ethnicity in the recent past, and on the growing centrality of competition for status (Gans 1979). Membership and identity have roots in both material and symbolic life. Naturally such dimensions either flourish through the development of culture and institutions, or fade away.

The second broad axis of the problematic gauges the increasing degree of tightness of a social arrangement: from membership, which may be regarded as a minimal set of conditions for belonging to a club (the difference between members and strangers), to identification/identity, involving the subjective recognition of some salient features as the basis for self-categorization, to culture, which represents a more or less “formalized” set of rules, laws, customs, and rituals, to institutions, which amounts to the development of a stable pattern of social interaction (Walzer 1983; Edwards and Doucette 1987; Roberts and Clifton 1982). The notions of membership, identity, culture and institutions are extremely difficult to define precisely. Some scholars have anchored essentialist definitions in certain selected traits. Others have insisted on some primordial features as determinant. A third group has defined these notions fundamentally in a relational way, as shared differences that are the results of negotiated arrangements (Drummond 1981-82). In the first two instances a number of ethnographic features are said to provide the basic or dominant characteristics necessary to qualify for membership (Nash 1989). In the last case membership, identity, and culture are in the nature of a persona, which is the result of a creative and interactive process through which relationships are constructed and evolve in a manner that makes them matter of conventions and agreements with outsiders (Goldberg 1980). In that sense, membership, identity, and culture may be regarded as increasingly complex, and stylized forms of arrangements or social capital (Coleman 1988). This symbolic capital simultaneously provides the basis for differentiation, structuration, and integration: it serves as a way to provide a basic partitioning based on negotiated differences, but also as a basis for assembling those disparate elements into a coherent whole (Porter 1979; Lussato 1989).

Since de facto heterogeneity may generate a segmentation of the social space into disconnected groups, and since such segmentation may well degenerate through multiplex relationships into cumulative processes accentuating and crystallizing such segmentation, an increasing degree of balkanization and anomie of the segments may ensue (Gluckman 1967; Laurent and Paquet 1991). Consequently, it is crucial that conventions be negotiated vigorously, and that the pattern of rights and obligations of each party be spelled out. Membership is going to be easier to negotiate than identity, and identity easier than culture, but corresponding to these different degrees of cohesion there is some sort of “moral contract” (Paquet 1991-92).

The third broad axis of the block identifies three complementary and yet intricately interwoven principles of social integration: ethnicity, nationality, and civil society. These are different grounds on which these moral contracts are negotiated or arrived at. The case of ethnicity used to be regarded as quite distinct because of the fact that membership was perceived as rooted primarily in physical characteristics and the material order. However, as ethnicity has tended to become more and more symbolic there has been a growing importance given to the symbolic order in defining ethnic boundaries. In that sense, ethnie, nation, and civil society are different ways of anchoring membership and identity that may be regarded as tending to become substitutes, or at least the basis for a complex compound, rather than being the basis of absolutely non-intersecting foundations. They are valid bases for discussing membership, identity, culture, and institutions, but, depending on what is the hegemonic or dominant terrain, the “moral contract” will contain a different set of collective rights and obligations. Determining the valence of each terrain becomes crucial.

Building a Lexicon

The ambiguity of a number of key concepts has always hampered discussion in the past, so some clarification may be useful at this time.

Pluralism is probably the most troublesome of these concepts. The word is used loosely, and there is no corpus stating clearly what a pluralist society is or what its fabric should be. We may approach it by way of the notion of the open society, developed and expounded by Bergson and Popper (Bergson 1932; Popper 1942), connoting societies that have escaped the dominance of holistic values and have managed to put the individual at centre stage. This has translated into the following characteristics: a private sphere for the individual, who enjoys freedom within that sphere; the principle of private property; the rule of law to regulate the relationships between individuals and states; and restricted power for the state, so that society is never allowed to become “closed” (Reszler 1990). A pluralist society, however, goes beyond this notion of negative freedom and calls for “an ensemble, composed of compartments freely agglomerated,” in which the constituent parts retain a good portion of their original autonomy, and are regarded as “irreducible domains in permanent interaction,” so that “each particular sphere finds its expression in a partial power” and there is a multiplication of allegiances corresponding to this division of powers (Reszler 1990).

At one extreme of the spectrum of pluralism, then, one may posit complete relativism and the cult of diversity qua diversity. This entails a multiplication of allegiances and a gamble on solidarity emerging as a result of a multiplicity of competitive focuses in the different cultural groups. At the other extreme, one may posit the unitary and closed society. One may imagine a gradation of intensities and interpretations of pluralism between these two poles.

Another central concept at the root of our notion of modern society is liberalism, with its central concept of individual autonomy that is meant to override, or at least firmly constrain, the emergence of any communal authority or cultural rights that may exclude non-adherents. Liberalism as a political philosophy provides an interpretation of what it means to belong voluntarily to a cultural community. Liberals, with their uncompromising defence of individual rights, have been somewhat hostile to group rights and even more to minority rights. Yet, in relatively more “enlightened” or “generous” versions of liberalism, nothing denies group rights, cultural rights or minority rights. All depends therefore on the notion of liberalism in good currency.

Thus, in Trudeau’s Canada, it was felt that “liberal equality was incompatible with the permanent assigning of collective rights to a minority culture;” this notion of liberalism posited the “idea of collective rights for minority cultures as both theoretically incoherent and practically dangerous” (Kymlicka 1989), for these rights would be deviations from the strict principle of equal individual rights. Kymlicka has argued that this is a truncated understanding of liberalism. If separation is a “badge of inferiority” in certain circumstances, “in Canada, segregation has always been viewed as a defence of a highly valued cultural heritage” and thus cannot be regarded as a “badge of inferiority.” Consequently, Kymlicka challenges the traditional view of liberalism and argues in favour of a broadening of liberalism to take minority rights into account. This is the same argument that Kolm has developed in connection with cultural rights (Kolm 1985).

At the centre of this reframing of liberalism is the value of cultural membership. This is a primary good for Kymlicka: in his view, if an individual is stripped of his/her cultural heritage, his/her development is stunted. This implies that a liberal view of equality need not be insensitive to social/cultural endowment: “members of the minority cultures can face inequalities that are the product of their circumstances or endowment … and … certain collective rights can be defended as appropriate measures for a rectification of inequality of circumstances.” What is required is a set of constitutional provisions that would be “flexible enough to allow for the legitimate claims of cultural membership, but which are not so flexible as to allow systems of racial or cultural oppression.”

While a liberal argument may be provided for cultural membership, the limits to be imposed on the use of such an argument are unclear. Some have used it to defend the equality of all minority rights, others have defended them only if they are rooted in shared projects, and others still would restrict its ambit to groups facing clear inequality of circumstances. Ralf Dahrendorf has referred to “wet” and “dry” liberalism to connote the looser and tighter versions of the liberal theory (Dahrendorf 1988). In a “dry” liberal system community rights do not exist, but in a “wet” liberal system they may. Yet these rights remain ill-specified and, given the divergence of views even among jurists on the question of the differences between private and public, or between civil society and the state, it is hardly surprising that so many incommensurable cases have been defended with equanimity on the basis of the same doctrine.

The debate on secession rights for minorities (Buchanan 1991) may provide a useful forum for the clarification of the terrain, but liberalism is likely to be a most unhelpful arbiter. Individual rights and collective rights have become so intermingled since the New Deal of the 1930s (Ackerman 1984) that any Solomonian effort to separate them, or to establish a definitive order or hierarchy in those rights qua rights, is bound to be futile (Bouchard 1990; Dumont 1990).

Liberal democracy’s emphasis on rights and on negative freedom— protection against interference with individual choices—has led to a phenomenal reductionism. Democracy, which originally meant putting the active citizen at centre stage, through government of the people, by the people, for the people, has expropriated citizens of this central governing work, which was part and parcel of being a citizen, in “rights societies” (Tussman 1989). Participation and, with it, the emphasis on positive freedom—being able to do this or be that, and the duty to help others in that respect (Sen 1987)—has been virtually excised. The whole range of notions of membership, identity, culture, and institutions connotes a sense of participation in ethnie, nation, or civil society that has consequently remained rather obscure and underdeveloped.

Charles Taylor has argued that there is a cleavage between “rights societies,” where the dignity of each individual resides in the fact that he or she has rights, and “participation societies,” where freedom, agency, and efficacy come from the fact that the individual has a recognized voice. This participatory model obviously presupposes “a strong sense of community” (Taylor 1985). For different societies, this process of identification with the community may be more or less important a characteristic. Moreover, the participatory institutions embodying it may not be equally congruent with the ethnie, the nation or the civil society. Different degrees of allegiance and belonging may spell out a multiplicity of identities based on the relative salience of these different communities in the life of citizens. This plurality of identities, or the legitimization of “hybrid identities” based on a plurality of participations in ethnie, nation, and civil society, has not developed evenly across national territories.

The rationale for participation is the very same that underlies the notion of group rights. Denise Reaume has provided a persuasive argument for the participatory nature of a number of goods, such as the maintenance of a language community (Reaume in Lafrance 1989). This complements the argument put forward by Taylor. This approach makes sense both of group rights and of the obligation for a substantial number of the group to participate. Michael McDonald has used a parallel line of argument to show that the “sharing of nomos and narrative makes possible public spaces that are common property,” and that rights to protect the existence, identity, and integrity of the communities sharing that nomos are as important as individual rights (McDonald in Lafrance 1989).

Culture connotes a whole way of life, so it would be unduly reductive to define it only on the basis of ethnicity, or with reference to an idealized and aseptic notion of civil society. Culture is more usefully defined in terms of communication. Social systems are those constituted as operating through communication. Culture is defined by how individuals and groups communicate through language and solve problems. Language is indeed a central operational common denominator, or the matrix on which culture is erected. Cultural values are underlying reference points in all these communication activities. Building on this communication notion of culture, cultural identity acts as a set of boundaries that, while facilitating communication within a community, may in fact frustrate communication with “the outside,” with those who are not part of the cultural group. In an “open society” that allows for respect for diversity, social cohesion, and nondiscrimination, language is a vector of communication, exchanges, and mixing (Bouchard 1999).

Fundamentally, each individual bases his or her own experience and action upon selections made by his or her ancestors to decomplicate reality. This cultural heritage enables each individual not to have to reinvent complexity reduction strategies anew in each generation, but it also requires that such choices and innovations be transmissible. As differentiation and diversity increase, the world visions of the different groups also become more differentiated and diverse, and the media of transmission also become differentiated. The challenge is to understand these different media of transmission, and the extent to which they may combine to ensure adequate learning, and complementary and not conflictive cognitive expectations. Moreover, while in traditional undifferentiated societies transmissibility was ensured through a shared construction of reality (community, religion, family, and so on), in differentiated societies the most significant media may be structures built on money, power, and other such factors, and one must be able to identify the relative efficiency of these different channels and their relative valence.

The Leverage of Cultural Diversity

As a general proposition, cultural diversity is regarded as a new reality that has to be taken into account in collective decision-making. It is also regarded by all, whether as a result of personal conviction or as a result of some degree of political correctness, as generally desirable. Yet the discussion dries up very quickly and drifts into generalities as soon as anyone tries to define, explicitly and verifiably, how cultural diversity is likely to improve the economy, society or the polity.

Indeed, as conversations proceed it generally becomes clear that, for many, diversity is primarily a constraint on social development, a problem to be managed. The arguments used indicate that the very fact of acting to preserve or maintain diversity—or homogeneity, for that matter—is regarded by some as an effort to stop the evolution of societies at a certain stage and to prevent the further development of heterogeneity—or, the other side of the same coin, to prevent the further erosion of homogeneity—instead of allowing the dynamics of evolution to prevail. While many observers are quite willing to bet on diversity, they feel that there is a need for the state to manage, or, at the very least, to monitor and accompany, this new reality, in order to prevent unintended consequences that might arise from such diversification being conducted too fast or without due diligence. For this latter group it is not reasonable to allow this process to proceed unattended. Indeed, this is perceived as being the case, not only because of the potential damage that it might generate, but also because of the fact that one cannot expect the highest and best use of diversity to emerge organically.

For yet another group of observers, diversity can only mean the end of consensus. Consequently, it must be tamed. While no one questions the reality of diversity, few would seem ready to accept unlimited diversity without significant safeguards, and yet very few feel strongly enough to make a specific case of the matter. This explains the cacophony, confusion, and malaise that erupted, for example, during the current debate on accommodements raisonnables (“reasonable accommodations”) in Quebec when a bold group dared to put a specific proposal about such safeguards on the table. As for the degree of diversity that can be regarded as appropriate, given the nature of the safeguards, little consensus emerges except at the highest degree of generality: that the optimal degree of diversity might not be the maximum degree, and that accommodements raisonnables need not be specified, for they simply exist.

To the extent that governments and states have diminished powers, they lose both their roles as protectors of civilization and as promoters of a pluralistic society. There is obviously no longer any guarantee that governments and states will either accept the responsibility of shouldering these roles or be able to perform them well. We have seen recently a sufficient number of states that have been character...