eBook - ePub

High Tide

How Climate Crisis is Engulfing Our Planet

Mark Lynas

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

High Tide

How Climate Crisis is Engulfing Our Planet

Mark Lynas

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is High Tide an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access High Tide by Mark Lynas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze biologiche & Scienza generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Scienze biologicheSubtopic

Scienza generale1

Britain’s Wet Season

It was still raining, and York station was in complete chaos. The railway track was underwater both north and east of the city, and trains for Edinburgh, Newcastle and Aberdeen were terminating there, disgorging their tired and confused passengers into the mêlée. People dragged their luggage in and out of crowded waiting rooms as train after train listed on the display board was cancelled. Harassed staff tried to show passengers alternative routes via local buses, whilst others simply fled from the station concourse, pursued by angry travellers demanding to know how they could ever reach their destinations.

It was the beginning of November 2000. By the end of the month Britain would have experienced some of the heaviest rainfall and worst flooding ever recorded. On the miserable Friday night I arrived in York, newspapers and radio shows were already buzzing with speculation. This wasn’t normal, everyone agreed. Floods had come and gone before, and Britain was supposed to be rainy. But no one could remember anything like this. There had to be some new explanation.

October had also been a washout. On 11 October Kent, Sussex and Hampshire received ten centimetres of rain – more than a month’s usual average in a single day. Sixty government flood warnings were issued for the southeast of England, and the residents of Uckfield awoke to find their town centre under more than a metre of water. Lifeboats rescued people stranded in their homes, and one shopkeeper was washed away by the rising flood as he tried to open his shop door. Horrified neighbours looked on as he was sucked down the high street by the torrent. ‘He didn’t even have a chance to scream, the water was so fierce,’ one told a Guardian journalist. (‘“Unheard of” rain sweeps the south’ was the newspaper’s dramatic headline.1) Happily, the shopkeeper was later found clinging to a riverbank.

Close by, a supermarket’s windows caved in under the pressure of the water, and stock began to float off the shelves and away down the street. In Lewes, a town downstream on the same river, council staff had to drive around with a loudhailer warning residents in low-lying areas to evacuate to higher ground. Six lifeboatmen were lucky to escape with their lives when their boat was nearly trapped under a bridge.

And still it kept on raining. The government’s countryside minister, Elliot Morley, was one of the first to acknowledge something unusual when he visited the area the next day. ‘We seem to be having more violent weather patterns and we accept that it could be due to global warming,’ he said.2

Was the minister right? Had climate change indeed come home to Britain?

York was dark and eerily deserted. The heavy rain had turned to heavy sleet, and just a few cars splashed through the huge puddles that had gathered in the road. I walked along beside the old city walls, down towards the river.

The Ouse was almost unrecognisable. There was no sign of a riverbank – instead the water reached right round the buildings on both sides, and was almost touching the top of the arches of the road bridge. In the glow of the streetlights it looked as slick as oil, but also seemed to be moving impossibly fast, swirling forcefully around the stones of the bridge. In both directions streets which had usually led to boatyards, pubs and restaurants were deserted, the bustle of people replaced with lapping black water.

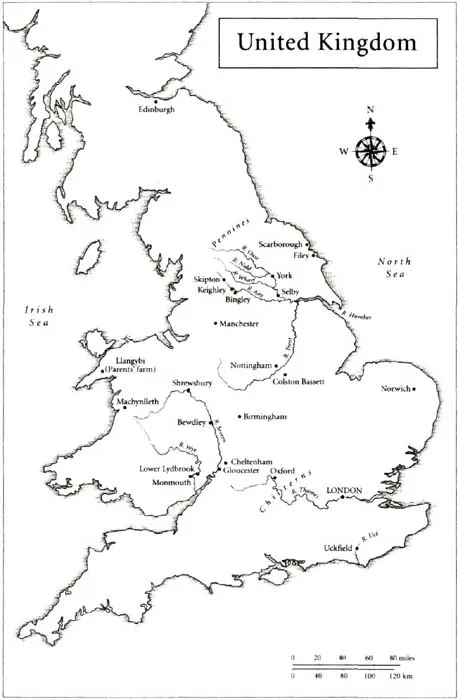

The worst of the rain had fallen two days earlier, when an intense depression – the remnants of an Atlantic hurricane – crossed the country, dumping several inches on the Pennine Hills. With the ground already saturated from previous deluges, the new water simply sluiced off into the rivers Nidd, Wharfe and Aire. The Aire valley was particularly hard-hit, and in the Yorkshire towns of Keighley, Skipton and Bingley families had been forced to camp out in leisure centres and bed and breakfast accommodation. Further downstream in Leeds the runoff overtopped embankments usually eight metres above the water level, turning city streets into canals temporarily reminiscent of Venice.

York is often hit by floods, but it was soon apparent that this disaster was off the usual scale. The day before I arrived, the Archbishop of York had paddled around his palace in a dinghy, whilst tourist rowing boats had been commandeered to evacuate an old people’s home. That day the water was within half a metre of breaching flood defences, which would have submerged another seven hundred houses.

On 2 November, as I peered over the bridge at the rising River Ouse, the nationwide floods were already the most extensive on record. But the worst was yet to come.

No one knew where I could catch a bus to Scarborough (the railway line was under a metre and a half of water at Malton). I found the coach almost by accident on the station forecourt, already besieged by bedraggled travellers, most of whom wanted it to be going somewhere other than Scarborough. Rain was still coming down in torrents and people hurried on board, shaking off their umbrellas on the bus steps. The journey took much longer than usual, and as we passed through the Yorkshire lowlands the darkness outside was inky black through the steamed-up windows.

My sister’s husband Steve was waiting in his car when we arrived.

‘The main road to Filey’s cut off,’ he said. ‘But there are other ways in on the country roads, so I’m pretty sure we’ll get through.’

As we left Scarborough the rain turned halfway back into sleet, and began to pelt down at an even more incredible rate. Steve had to slow right down, and with the headlights on full beam the drops falling from the sky seemed to unfold like curtains. Water was simply sheeting off the fields into the road, collecting in any dips and low points in large ponds. We passed a big roundabout near Filey which was almost entirely submerged. In the flashing headlights of an emergency vehicle I could see a stranded car in what looked like a lake. We tried several other routes, before finally making it through to Filey on the last open road.

The scale of the damage became clear next morning. Just across the street from my sister’s house is a small stream which runs down to the beach in a narrow cutting, next to a tarmac path which is shaded by trees in the summer. All the way down the valley the path had been ripped up – huge slabs of tarmac tossed around and dumped with piles of other debris on the beach. Rubbish was stranded a metre or so up the trees, showing how high the water level had reached. I hadn’t seen it happen, but it was clear that what had taken place in that quiet valley was virtually a flash flood. Filey was still officially cut off, and all the way along the back of the beach mudslides had fallen from the saturated cliff face. In the town itself, various front gardens had turned into small lakes.

Even then it didn’t stop raining. There was a brief respite for a couple of days, but weather reports identified another storm already gathering out in the Atlantic, where higher-than-average sea surface temperatures were giving the depressions more energy and moisture than usual. In York more than 4000 homes were evacuated as the river crested at levels unmatched in over a century. The tiny village of Naburn, just south of the town, became an island – veterans of the Mozambique floods from the International Rescue Corps were drafted in to help safeguard lives and belongings. Nationwide the death toll now stood at eight. In Naburn there was some good news: a baby was born, tended by a midwife also marooned on the new village-island, and the milkman was still able to make deliveries, albeit by Land-Rover.

On Sunday I returned to York – by road, since the railway was still cut off – to find a city under siege. The sense of crisis was heightened by crowds of sightseers, and by TV crews giving breathless live reports in front of the still-rising river. Brown water lapped around the foot of the castle mound, and in many riverfront streets pumps were fighting to extract water from basements, multiple hosepipes discharging back out into the road. On the west side of the river sandbags had been piled high along the tops of walls.

As I walked around, leaks were springing up everywhere, leading in some places to mini-waterfalls cascading down the bank of sandbags. On the other side of this fragile barrier thousands of tonnes of river water were perilously close to escape – a fact that seemed lost on all the people who, like myself, wandered around carelessly below river level to take pictures. Somewhere on the other side of the defences was a riverside park, though only trees and the tops of bushes testified to its continued existence.

York escaped complete disaster by a mere five centimetres that day, although a thousand properties had already been submerged. It was the worst flooding in four hundred years of records. The River Ouse had peaked five and a half metres higher than normal, and the city centre was only saved by the round-the-clock efforts of police, soldiers and firemen shifting 65,000 sandbags to hold back the water.

And York was far from alone – in Shropshire, Shrewsbury was also being hit hard, as was Bewdley in Worcestershire. Downstream from York a lake the size of Windermere, the largest in the English Lake District, had formed: as my train travelled south back down to Oxford, passengers gawped at the new inland sea (complete with large white-capped waves) which had obliterated fields for miles on both sides of the raised track.

As people cast around for a cause, different theories were advanced. Some blamed new housing developments on river floodplains, whilst others claimed that new farming practices meant that water ran off ploughed fields too quickly. But although both may have played a role, they were far from being the whole story. The truth was much more straightforward: Britain had simply been deluged with a staggering amount of rain.

More than three times the normal monthly average of rain fell in parts of the southeast and Yorkshire. Whilst in most places the deluges were judged to be a once in a century event, rainfall totals were sometimes so extreme that they far outweighed previously-observed natural variability. Plumpton in East Sussex recorded 144 millimetres in a single twenty-four-hour period, something that would be expected only once every 300 years,3 whilst the River Uck catchment in the same county had a thirty-day rainfall total that should only occur once every 650 years.4

Most floods come and are gone again in a few days at most. But in October and November 2000 storm relentlessly followed storm, leaving no time for the water to drain away. In England and Wales the September to December 2000 rainfall total was the highest since records began in 1766. In major river basins the floods were the most extreme of any ninety-day period on record, and for shorter time periods were only outranked by the March 1947 ‘Great Floods’ – which had been generated by rapid snowmelt and rain running off still-frozen ground, and thus were much briefer.5

But even very extreme events – which happen only once in a lifetime or even less – can still be part of the natural variability of the climate. A single flood, however dramatic and destructive, isn’t enough to convince a scientist that global warming is to blame. In order to be able to identify more clearly humanity’s telltale fingerprint on the climate, there has to be a trend – evidence of a definite longer and wider change for which other causal factors can be confidently ruled out.

THE ‘SMOKING GUN’?

As it happens, such evidence is indeed available for the UK. To find out more, I went to visit the climatologist Dr Tim Osborn at the Climatic Research Unit (CRU), part of the University of East Anglia. It was almost two years to the day after the start of the autumn 2000 disaster, and there was a hint of winter in the air as the London train sped through the Essex town of Colchester, past the River Stour saltmarshes and on through the flat Norfolk fenlands to Norwich.

As so often, Osborn confounded my expectations. No white lab coat for him: instead, a youngish, fair-haired man in shorts, trainers and a red golfing T-shirt was leaning over the balcony three floors above as I arrived at the round, glass-fronted CRU building.

‘Hello! Come on up,’ he shouted as I climbed the stairs. His room was strewn with back copies of the International Journal of Climatology and meteorology books, as well as sheafs of paper – many covered with impenetrable algebraic scribbles.

‘Sorry about the mess,’ he said as I sat down on a free chair. Then he swivelled his own chair round to face the computer screen. ‘Now, have a look at this.’

Osborn has spent years analysing nearly half a century of rainfall statistics. From a damp day in 1960s Blackpool to a torrential summer downpour in 1990s Devon, all these records were fed into his number-crunching computer. When spat out the other end into a series of graphs, these statistics – rather than just showing the usual random vagaries of the British weather – showed that something very unusual was going on. In fact the trend was so clear that even Osborn himself was ‘surprised’ by what it revealed.

What Osborn discovered was that over recent decades heavy winter downpours have indeed increased dramatically. ‘Over the period from the 1960s to the mid-1990s there was a doubling of the amount of rain that came in the “heavy category” in winter,’ he explained. ‘So in the 1960s something like seven or eight per cent of each winter’s rainfall came from what we call the “heavy” events, whilst by the mid-1990s that had increased to about fifteen per cent.’6

With more rain falling in a short time, river systems were unable to cope – and floods were the inevitable result. What’s more, this heavier winter rainfall was directly related to rising atmospheric temperatures.

Straightforward atmospheric physics suggests this could be the global warming ‘smoking gun’. The relationship between temperature and the air’s capacity to hold water vapour is not linear – in fact the air can hold proportionally more water as temperature rises.7 So in a given ‘precipitation event’, whether it is snow, hail or rain, more water is available to fall out of the sky over the same short period of time.

This is exactly what seems to be happening in Britain: as a result of global warming, more warm, saturated air rushes in from the Atlantic, causing stronger storms and heavier rainfall. As a result, the probability of heavy rainfall has doubled over the last thirty-five to forty years in southeast England, according to observations and analysis conducted by Osborn and his CRU colleague Mike Hulme.8

These aren’t one-off downpours, either. The frequency of prolonged five-day heavy rainfall events has also been increasing. In Scotland floods have been getting far more frequent over the last few decades, whilst in England and Wales there have been four major floods in the last twelve winters: 1989/90, 1993/94, 1994/95 and, of course, 2000/01.9 The match for 2000 isn’t perfect because the worst flooding came during the autumn – but the floods also lasted right through until January, just as the trend would suggest.

Osborn’s work also coincides with evidence from other parts of the world. Study after study has come to the same conclusion: that throughout Earth’s mid-latitudes, rainfall is getting heavier and more destructive. There has been a steadily increasing rainfall trend in the United States through the twentieth cen...