- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Battle Castles by Dan Snow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

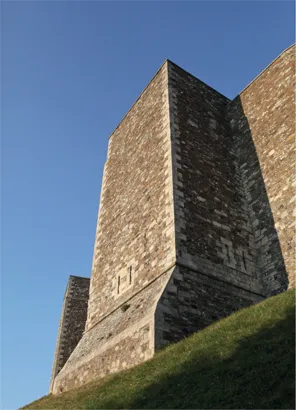

The sun sets on the concentric defences of Dover castle, the ‘key of England’

On 22 May 1216, King John stood disconsolately on the Kent shore at Sandwich. A few days earlier a terrible storm had scattered the powerful fleet which he had gathered to defend his realm and to keep an invading army at bay. From his vantage point he could now see, anchored off the coast a little to the north, the invasion fleet of Prince Louis, the son of the French King and claimant to his own throne. The prince had landed safely on the Isle of Thanet the day before. Exactly 150 years after the first Norman invasion, an army from France was yet again trying to unseat the King of England. With a sizeable fifth column to assist him, the prince came at the invitation of an English rebel army, determined to make John pay for what it deemed his arbitrary and tyrannical rule.

After sounding his trumpets on the beach, King John fled south back to Dover, leaving his bewildered followers behind. His formidable castle – begun by his father, Henry II, continued by his brother, Richard I, and latterly King John himself – would become a crucial stronghold in the coming struggle. The castle was besieged not once, but twice, by Louis’ substantial armies. At times it seemed that this great bastion was all that stood in the way of Louis’ formal recognition as King of England. It was in relation to the events of 1216 that the chronicler Matthew Paris later described Dover Castle as ‘clavis Angliae’ or ‘the key of England’.

John, King of England (1199–1216) has gone down in history as one of the worst English rulers, in large part because he presided over the fall of the Angevin Empire

© The British Library Board

A thirteenth-century illustration of Thomas Becket’s infamous murder at the altar in Canterbury Cathedral. King Henry II bitterly regretted the incident

© The British Library Board

THE MURDER OF BECKET AND THE BUILDING OF DOVER CASTLE

The origins of Dover’s construction and pre-eminent status are to be found in the reign of Henry II, and a political crisis even more famous than that which afflicted his son. At dusk on 29 December 1170, the Archbishop Thomas Becket was brutally hacked to death by a party of knights in his cathedral church at Canterbury. According to an eyewitness, his brains were scattered across the floor while the monks sang Vespers in the choir above.

Whether or not he had deliberately incited the murder, Henry II was universally held responsible and was later to make an astonishing public penance. This formidable man, described by a contemporary as having ‘a large, round head, grey eyes that glowed fiercely and grew bloodshot in anger, a fiery countenance and a harsh, cracked voice’, submitted to three lashes from each member of the cathedral’s eighty-strong monastic community.

Within days of the archbishop’s sensational murder, word spread that Becket was working miracles from beyond the grave, encouraging a cult that attracted international attention. In 1179 the King of France landed at Dover to make a pilgrimage to Canterbury and was conducted to and from the shrine by Henry II himself. The following year the saint’s tomb was made the centrepiece of a new cathedral being built at Canterbury.

Henry II, King of England (1154–89) is frequently hailed as one of England’s greatest monarchs. Under his rule the Crown’s dominions on the continent grew rapidly and the English legal system evolved considerably

Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland, MS 700, f. 72r.

It can hardly have been a coincidence that Henry II started to pour money into the castle at Dover soon after Louis’ visit. This strategically-placed castle straddled the approach to Canterbury from the Continent. Here at Dover, the hub of one of Europe’s most important communication routes, Henry needed to respond architecturally to the burgeoning cult of his great rival and critic. The sheer scale of the project in financial terms speaks clearly of its perceived importance. Over the following eight years, the royal financial accounts record a total expenditure of nearly £6,000 on Dover Castle, from an estimated royal income of about £10,000 per year. These accounts, known as the Pipe Rolls, got their unusual name from the tradition of attaching each year’s record to the last and the document being rolled into a pipe shape. Dover could plausibly claim to be the single most expensive secular architectural commission of Henry II’s long reign.

The castle’s location and site had been chosen carefully by Henry. It offered the shortest sea-crossing between England and the European mainland. Set on a hill above the mouth of the River Dour it was a natural place to fortify, and previous castles are known to have existed on the site. There may have been an Iron Age hill fort. By about the year 1000 there was certainly a fortified settlement, if not a castle, within the U-shaped ditches, dropping to the sea, which still define the modern site. Not long after the Norman Conquest a chaplain of William the Conqueror, William of Poitiers, wrote of a castle at Dover which ‘stands near to the sea on a rock which is naturally steep on all sides’, and which had been ‘patiently chipped away with iron tools, so that it is like a wall of towering height equal to the flight of an arrow on the side washed by the sea’.

The Roman ‘pharos’, or lighthouse, within the grounds of Dover Castle. It was one of two beacons for guiding sea traffic, and may have stood at almost twice the height it does today

Castles which would prove significant during the invasion of Prince Louis of France in 1216

What Henry II created here was a massive keep, or great tower, within its own enclosure or bailey. At over 27 metres high and 30 metres square it was one of the largest ever constructed in Britain. It was the pinnacle of a building tradition in which castles were built with a powerful central keep (the walls at Dover were in places nearly seven metres thick) which both provided accommodation for high-status residents and served as the core defence in times of crisis (see The Keep box). Dover was the final link in a chain of such fortifications which ran along the route between London and this most important port for shipping to the continent: from the Tower of London through Rochester and Canterbury to Dover. Its form, moreover, echoed and was echoed by royal castles across the Plantagenet Empire.

The fact that the buildings at Dover were laid out to the north of the old castle enclosure removed the need to demolish the most important of the existing buildings. There was a small Anglo-Saxon church, known as St Mary-in-Castro. Immediately next to it, there was also an ancient lighthouse, or ‘pharos’, wrongly believed to have been built by Julius Caesar as his treasury in Britain, which lent prestige and symbolism to the site (though it was probably built between AD 117 and 140).

Dover Castle’s Great Tower. The walls of Henry II’s keep are over six metres thick in places – wider, on average, than the top of the Great Wall of China

Unusually for the period, the walls of Henry II’s great tower and inner bailey were punctuated by a multitude of rectangular towers. Pale Caen stone from Normandy, in precisely-cut blocks, was used to finish the central section of the entrance façade and to create stripes across the other three sides. A late-twelfth-century traveller arriving across the Channel, being confronted by this fantastical, turreted structure rising up from the white cliffs, must have found this hugely striking and impressive. The fact that these bailey towers incorporated arrow loops within their lower storeys created a second level of defence beneath the wall walks – a novel idea in mid-twelfth-century English castle design. The configuration today reflects the fact that in the eighteenth century the loops were reordered to cater for muskets.

To either end of Henry’s new bailey were two gates, each protected by a walled outwork. Such gateway fortifications, or ‘barbicans’, were a relative novelty in castles of this period. The term derives from the Arabic words bab (gate) and khan (courtyard or enclosure) – perhaps the most convincing connection made between the European Crusades in the Middle East and English castle architecture.

On the north side, Henry’s keep was laid out with stripes of light Caen Stone and dark Kentish Ragstone, used for strength but also for decorative purposes

The southern barbican formed a combined defensive structure with the older defences in the area of the Roman pharos. There is evidence of changes to the ancient buildings at this period: architectural fragments from St. Mary in Castro are similar to those found in the great tower. Beyond the northern bailey gate and barbican, meanwhile, was a timber bridge, one support of which remains encased in a later masonry ramp. This bridge probably led to an outer gate on the landward tip of the castle enclosure, the site of the castle’s future great north gate.

A reconstruction of how Dover Castle’s defences may have looked in the early thirteenth century

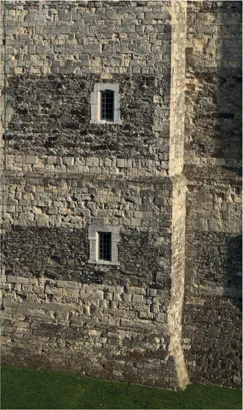

Arrowloops in the lower section of an inner wall tower. With the advent of gunpowder weaponry, crenellations were removed from the top of the tower

The Palace gate on the south side of the inner wall

Besides the new fortifications, Henry was evidently concerned to create domestic apartments that could accommodate royal visits and important guests. The rooms of the great tower itself were luxuriously appointed, with their own piped water supply. The private rooms, furthermore, reveal an intriguing insight into the castle’s early history. Among the rooms of the great tower were two chapels, with rich architectural sculpture identical to that found in the works at Canterbury Cathedral (which were being carried out at the same time). Revealingly, we know from a slightly later document that one of the chapels became dedicated to the man who had enraged Henry in life, but whose death had forced him to repent and to confront a growing international pilgrimage network centred on Canterbury: St Thomas Becket.

A stone bridge now stands where a timber bridge once led to the inner wall’s northern barbican

The northern barbican as seen from the inner wall. Attackers were confronted by a long diagonal route to the King’s Gate while under attack from the wall’s defenders in this ‘killing zone’

The Pipe Rolls record that the senior mason responsible for the work at Dover from 1181 was Maurice ‘the engineer’; he was, most likely, also the principal architect. This was almost certainly the same Maurice ‘the mason’ who worked on Henry’s great tower at Newcastle-upon-Tyne from 1168. In fact, however, though there are points of similarity between the planning of Maurice’s towers at Dover and Newcastle, in terms of architectural detail they are quite different. The contrast suggests that in both cases locally engaged masons influenced the architecture of the respective buildings. At Dover, the style of the architectural sculpture suggests, as we have seen, that the masons working on t...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Dover Castle

- 2 Château Gaillard

- 3 Krak Des Chevaliers

- 4 Conwy Castle

- 5 Malbork Castle

- 6 Gibralfaro Castle

- Keep Reading

- Contributor Biographies

- Further Reading

- Acknowledgements

- By the Same Author

- About the Publisher