eBook - ePub

The Dawn Watch

Joseph Conrad in a Global World

Maya Jasanoff

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Dawn Watch

Joseph Conrad in a Global World

Maya Jasanoff

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Dawn Watch an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Dawn Watch by Maya Jasanoff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

NATION

ONE

NO HOME, NO COUNTRY

THREE WEEKS BEFORE CHRISTMAS, 1857, a friar from the Carmelite monastery in Berdychiv, Ukraine, walked in sandals over the ice-glazed ground to perform the baptism of a firstborn son.1 He sprinkled the infant three times with holy water, christening the baby with the names of his mother’s father Józef, his father’s father Teodor, and a hero of Polish patriotic literature, Konrad. God has regenerated you, said the priest to Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski—anointed with a family’s history and hopes.2

The baby’s father, Apollo Korzeniowski, swelled with a sense of occasion. The birth of a first child makes history for any parent, and Apollo experienced it as profoundly political too: a moment to reflect on the destiny of his nation, Poland, which had ceased to exist as a state. Berdychiv had once been part of the independent Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, but at the end of the eighteenth century the Commonwealth had been swallowed up by its neighbors in three giant gulps. Now Austria ruled the southern province of Galicia; Prussia governed the northwest; and Russia had snatched everything else, a huge tranche of land encompassing nearly all Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine—recovered lands of the Russians, said Catherine the Great; “stolen lands,” said the Poles.3 Almost overnight, Ukraine’s Poles became a pebble in the boot of Europe’s most autocratic empire.

Apollo was a writer by vocation; he made the political into the poetical. He composed a song for the christening day. “To my son,” he began, “born in the 85th year of Muscovite oppression”:

Baby son, sleep without fear.

Lullaby, the world is dark,

You have no home, no country …

Baby son, tell yourself,

You are without land, without love,

Without country, without people,

While Poland—your Mother is in her grave.

Forget about joy, pride, relief, or any of the other happy emotions a parent might express on the safe arrival of a healthy child. Apollo’s lullaby was a dirge for a baby orphaned at birth, in mourning before he’d had a chance to live. Apollo approached the future as through a tunnel. There were restricting walls, Russian imperial rule; there was a light at the end, Polish independence; and the challenge was to keep going until you got there. That’s why he liked the motto “ubi crux, ibi poesia”: where there’s a cross, there’s poetry—or as he used it, where there’s a cause, there’s hope. He urged bravery and resilience, devotion and patience. “The time will come, the days will pass,” he concluded, and by God’s grace, Konrad would see Poland resurrected.4

Apollo meant his verses to inspire. Yet as he cradled this warm parcel of balled fingers and buttoned eyes, he couldn’t possibly anticipate how these words would resonate—how psychological darkness would torture Konrad, how loneliness would trail him, how far he’d travel into other lands, among distant peoples, before finding some kind of home. Apollo couldn’t imagine how his encouragement might read in retrospect like a curse.

THERE’S AN OLD POLISH EXPRESSION about the town where Konrad Korzeniowski was born on December 3, 1857. When you tell someone to “send a letter to Berdychiv,” you mean “send a letter to nowhere”—you’ll never reach me.5 The saying plays on Berdychiv’s nineteenth-century position as a “somewhere,” particularly for the town’s then-majority population of Jews. Berdychiv hosted numerous trade fairs every year, making it a routine stop for peddlers with no permanent address. If they said “send a letter to Berdychiv,” they meant send a letter to a place I’m going—you’ll definitely reach me.

The world is made up of “nowheres” and “somewheres”—but which counts as which depends on what “where” you look from. The story of Konrad’s life, and the world in which he lived, was a story of nowheres colliding with somewheres. At the time of his birth, the failure of a bank in Ohio touched off a financial panic that toppled firms in Hamburg.6 British troops struggled to suppress a rebellion in India. Indian troops sailed to Canton to threaten Chinese imperial officials.7 Chinese settlers rebelled on a river in Borneo, in a Malay state ruled by a European.8 European cloth and guns were traded up the Congo basin for ivory by villagers who’d never seen a white person.9 An American filibuster was booted out of Nicaragua. American-made steamboats plowed up the rivers of South America, and a locomotive built in Leeds pulled the first train out of Buenos Aires.10

Though Konrad would grow up to follow quickening, lengthening routes of trade, money, and people, into every continent, his journey started in a place, Poland, that was literally nowhere on a map of Europe, wiped away by the partitions of 1772, 1793, and 1795.11 But to Konrad’s fervently nationalist parents Apollo and Ewa, Poland was the only somewhere that mattered. The worldview they gave their son resembled a kind of tunnel vision.

History sits heavily on some backs. Konrad’s family stumbled into the nineteenth century under its weight. They belonged to a privileged class of landed gentry, the szlachta, that traced its descent back to the mythical founders of the Polish nation. Encompassing one in ten Poles, szlachta might be rich as princes or poor as peasants, but every one of them enjoyed rights ranging from a coat of arms to freedom from arbitrary arrest. Every male szlachcic was eligible to hold government office and got to vote for representatives to parliament, which in turn elected the king.12 Once considered the civic spine of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a “republic of nobles,” szlachta lost their privileges in the Russian Empire, and felt a special responsibility to restore an independent Polish state.

Konrad’s parents grew up in the shadow of defeat. In 1830 nationalists launched a major insurrection in the Polish-majority heartland around Warsaw (called the Congress Kingdom) but were beaten back by the Russian army in 1831. The tsar abolished the province’s parliament, imposed military occupation, and clamped Russification policies onto education, law, and religion. The regime went on to confiscate the estates of five thousand szlachta, deport eighty thousand civilians to Siberia and points east, and force a hundred thousand Polish soldiers into brutal military service in the Caucasus. More fortunate were ten thousand or so insurrectionists who emigrated, swelling the ranks of the Polish nation in exile, capital city Paris. There, politicians plotted their comeback to the resonant cadences of the refugee Adam Mickiewicz’s poetry, and the tunes of the émigré Fryderyk Chopin’s mazurkas and polonaises.13

What do you do when your history has been hijacked, your language suppressed, your religion marginalized, your mode of life scorned and straitened? The two most important men in Konrad’s life—his father Apollo Korzeniowski and his maternal uncle Tadeusz Bobrowski—came up with two different answers. On the Bobrowski side of the family, Konrad learned of forebears who tried to make the best of a bad hand. Konrad’s maternal grandfather judged the 1830 insurrection “the height of folly” and stayed put in Ukraine while his rasher friends rushed to join.14 His reward was relative wealth. When he died in 1850 he left six thousand acres and 360 male serfs to offset his debts, as well as a distillery, tavern, mills, and a stable of exceptionally elegant horses.15 Konrad’s uncle Tadeusz, then only twenty-one, took over as head of the Bobrowski family. Tadeusz loathed the Russians as much as anyone, but accepted tsarist rule as a hard truth. He invested his political energy instead in practical questions like land reform and peasant emancipation.16

On the Korzeniowski side of the family, Konrad learned of relatives who fought back. Konrad’s paternal grandfather, a veteran of the Napoleonic wars, raised a cavalry regiment in 1830 at his own expense and rode off to fight the Russians. His penalty was financial ruin. The family had to move away from their handsome ancestral estate and settle in a different district, where Konrad’s grandfather scraped along by working for the government, managing another Pole’s confiscated land.

Konrad’s father Apollo, just eleven years old when the rebellion failed in 1831, experienced national defeat as personal calamity. He found solace in the verse of Romantics such as Mickiewicz, who sang of Poland as the “Christ of nations” and filled a generation of young szlachta with odes to faith, courage, resistance, and love.17 As a student of languages at St. Petersburg University in his early twenties, Apollo joined a thriving literary underground where Polish students swapped censored texts in smuggled foreign reprints (called “blotting paper”), or manuscripts painstakingly copied by hand.18 Apollo began to publish himself: a play, a volume of poems, and a translation of his favorite French author, Victor Hugo.19 Literature gave him what the army had given his father: a place to find meaning, to act on beliefs, to fulfill a sense of duty. If you had no power in politics, you could use the power of poems—and if autocrats wanted to censor your words, you could resist them by speaking into silent pages, passed furtively among friends under false covers.

Tadeusz Bobrowski, ever the pragmatist, detected in Apollo some of the empty-headed utopianism that had ruined Apollo’s father, “always ready without a moment’s thought to mount his horse and drive the enemy from our land … Everyone knew that some time ago this szlachcic had fought well—and few stopped to ask whether he could think well.”20 For Tadeusz, to be a noble was to inherit a political fantasy. One’s duty was to get on with reality. He scoffed at Apollo for always trumpeting his szlachta status by “rather pretentiously” including his noble clan name, Nałęcz, when he signed his name.21 But it wasn’t mere snobbery that made Apollo do it. To be a noble, for Apollo, was to inherit a tradition of political freedom. One’s destiny was to reclaim it.22

Apollo returned from St. Petersburg in 1846 to the daily tedium of managing an estate in rural Ukraine. He loathed living among provincial, unpoliticized rustics.23 “I sometimes think that I have landed in the wild forests of America where hordes of monkeys mock a stray human being,” he complained.24 Two objects of love sustained him.

The first was Ewa Bobrowska, Tadeusz’s sister. Born in 1831, she was only sixteen when they met, yet already a great beauty, and “educated at a higher level than was common for our women in her day.” He was smitten. She was “his Beatrice, … full of charm and intelligence, a refined Ukrainian girl with the heart of an angel.”25 With his sharp conversation, urbane tastes, and striking, some said ugly, looks, Apollo cut a dash in provincial drawing rooms. But it was one thing to have him to tea, quite another to have him court your daughter. Ewa’s mother “suspected him of having a frivolous temperament and irregular habits,” while her father “found him lacking in practicality and resourcefulness,” more likely to be wasting his time “reading, writing and riding than working.” To put Apollo off Ewa’s scent, her father took him on social calls around the district, hoping he’d fall for another girl, but Apollo “always managed things cleverly enough so that either the young woman herself or her parents did not take to him.” Though her family didn’t yet detect it, Ewa, too, was captivated, and “spurned all other suitors’ advances” for Apollo’s sake.26

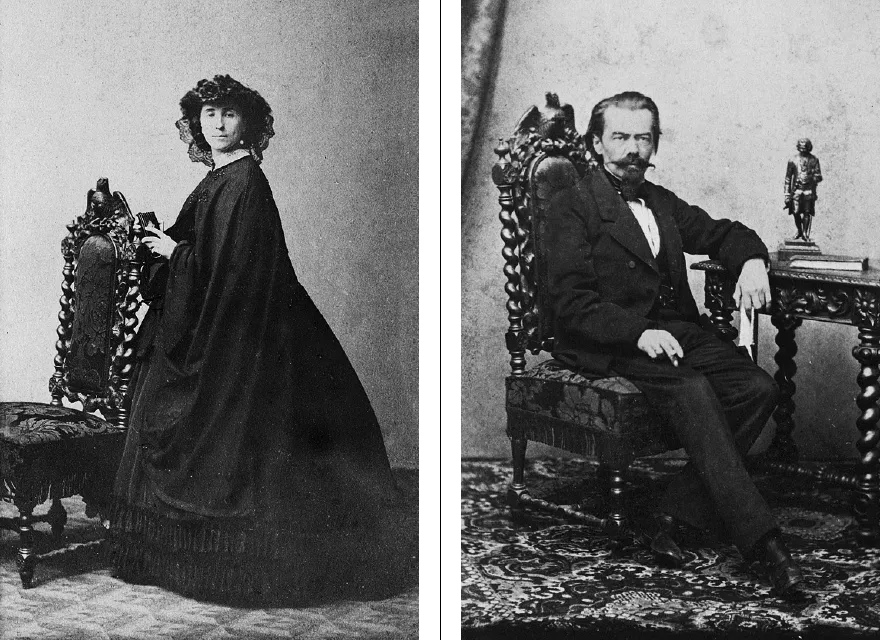

LEFT: Ewa Korzeniowska, née Bobrowska.

RIGHT: Apollo Korzeniowski.

Apollo remained equally steadfast in his pursuit of his other great passion, Poland. He wrote, watched, and waited for the moment to rise. Would it be 1848, when democratic revolutions swept across Europe? Not yet. Or 1854, when Britain and France launched a war against Russi...