eBook - ePub

England's Lost Eden

Adventures in a Victorian Utopia

Philip Hoare

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

England's Lost Eden

Adventures in a Victorian Utopia

Philip Hoare

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A kaleidoscopic story of myth, Spiritualism, and the Victorian search for Utopia from one of the brightest and most original non-fiction writers at work today.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is England's Lost Eden an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access England's Lost Eden by Philip Hoare in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia britannica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

StoriaSubtopic

Storia britannicaPART ONE

Green and Pleasant Land

Midway this way of life we’re bound upon, I woke to find myself in a dark wood

Where the right road was wholly lost and gone

Dante, The Divine Comedy

ONE

A Voice in the Wilderness

I am the voice of one crying in the wilderness,

‘Make straight the way of the Lord’

‘Make straight the way of the Lord’

John 1:23

When I was a boy, we’d often drive into the forest. With my father at the wheel of our Wolseley and my mother at his side, the world seemed as secure and bound and polished as the big old car itself. I would lie back and look up through the rear window at the trees passing hypnotically overhead. They seemed both remote and near as I looked out for a particular row of pines which reminded me of the day I lost my toy koala bear – his rabbit fur and shiny snout the source of deep solace – on scrubby cliffs above a Dorset beach where, for all the hours of searching, he was not to be found.

Now, forty years later, the westbound train crawls through Southampton’s outer suburbs, as if the city’s gravity were reluctant to let it go. This is the rear view, where England turns its back on itself, as if ashamed of its own history. Here the houses look into their few square yards, denying their communality with leylandii and larch-lap; here where subtopian dreams meet suburban reality. Then, gradually, the tarmac gives way to gravel, concrete to grass, allotments to wide heaths where pole-straight silver birch stake out new territory, screening the sky with their filigree bronze branches, standing guard over rutted ground riven with stony rills like frozen waterfalls. This land is open and limitless, laid bare in a way we have forgotten; we know contours only through gear changes, as our towns and cities gather together, seeking safety in numbers for fear of nature and its unpredictable ways.

At Brockenhurst, I haul my bike onto the empty platform. The forest station still seems rural, with its two-stop line to Lymington and a waiting room decorated with photographs by Julia Margaret Cameron, given in memory of her son and intended to beautify this connexion between London and her home on the Isle of Wight. But now visitors are greeted by letters spelt out in ballast on the side of the track Welcome to Brock. Beyond the village, with its butcher selling venison and its stockbroker-belt guarded by expensive cars, the B-road races the railway to the coast, while on the horizon the Island hovers where clouds should be, a lowering landmass separated by the unseen sea.

The wind is against me as I cycle over the open heath, and I’m grateful for the descent into the village of Sway, its outskirts marked by a tall stone cross. Remembrance wreaths still lie on the war memorial, their scarlet paper poppies faded by the sun and spotted by rain; propped up on the railing is a discarded hubcap. Dipping into the valley beyond, the lane darkens with tall trees. I turn off into Barrows Lane, where a hand-painted sign announces Arnewood Turkeys, but this is no ordinary farm building. Concrete where the rest of the forest buildings are brick, its classical proportions, domed roof and pillars resemble some strange escape from the Italian countryside. Beside it, in an overgrown field, is a stubby campanile, a plastic bag flapping from its unglazed window. Seemingly unfinished – as if its creator intended to return to his handiwork – this fairytale towerlet labours under an ivy burden. But it is dwarfed by the structure in whose shadow it lies, an eminence impossible to ignore, yet so unexpected that you could pass by without raising your eyes and miss it entirely. Reaching up out of the forest is an immense grey column, rising two hundred feet into the sky. Its very shape seems to change with the clouds – a sun-lit gnomon from one angle, a mad church steeple from another.

It is so bizarre that it seems completely detached from its surroundings. Over the road, a hard-hatted engineer perches at the top of a telegraph pole, barely aware of the tower that looms over him, just as I cannot remember it from my childhood visits to the forest. Perhaps it is a mirage, appearing only fitfully. Or perhaps it is part of some vast underground complex, some covert scientific experiment. The stillness of this unnamed country lane invites conspiracy: there is no sign of life, no one to acknowledge or explain this extraordinary structure. Omnipresent but forgotten, it refutes the curiosity of the modern world, as though gagged by its own mystery.

As I cycle on, past hedgerows which billow up like green pillows on either side, the tower’s shadow seems to follow me. The houses and cottages multiply as I approach Hordle. Here the roads have names, oddly evocative – Silver Street and Sky End Lane – but it is a disparate place, this arbitrary settlement rescued from the suburbs of nearby New Milton only by the proximity of the forest, whose presence is ever obvious and yet remote. These houses stand just outside its invisible boundaries, yet they cannot but be a part of it, as if its greenness were drawing them in, ineluctably.

I cross the busy east – west road, with its traffic hurtling towards Bournemouth, and ride up Vaggs Lane. Here the land is palpably higher, blown by secondhand gusts from the sea. Behind an orchard of exhausted apple trees is a petrified pine stripped of its bark, skeletal, as if lightning-struck. I knock at the door of a nearby house. A young teenage boy in combat trousers appears, restraining a dog.

‘Alright mate,’ he says, his chummy tone undermined by hesitancy and poshness.

I explain my mission. He points me back in the direction from which I came.

‘Are they friendly?’ I ask.

The boy shrugs: it was an old people’s home before the new owners took over. I retrace my tracks and pull up outside the gates. Opposite is a metal-barred entrance on which a notice has been pasted: NO DUMPING OUTSIDE THESE GATES BY ORDER OF THE DEPT OF THE ENVIRONMENT. Below it is a rusty white van, bits of old car engine, and an assortment of scrap metal and tin cans.

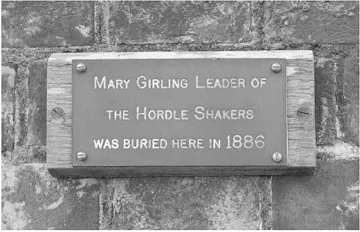

The gravel crunches as I walk up to the door. No-one answers the bell, but a pair of dogs growl at the side gate. The house is bigger than it appears from the road, the land around it lush pasture. I peer through the windows and try to imagine what this place was like a century and a half ago, when its inhabitants sought heaven on earth and this country lane erupted to scandal and sensation. Back down the lane I wander into the village churchyard, where gravestones stand shoulder to shoulder, many decorated with artificial flowers. Screwed to a buttress of the building, overlooking an oddly empty part of the churchyard, is a plaque of the kind made by shoe repairers in shopping malls.

Yet no trace of Mrs Girling’s grave remains. It is an absence which is doubly appropriate, for her followers claimed that three days after her interment, their leader rose from the dead.

Once these fields echoed to one hundred and sixty-four men, women and children speaking in tongues and dancing in ecstatic rites, living celibate, communal lives as they awaited the millennium. Now there is nothing left to show for their utopian aspirations: no buildings, no books, no artefacts; nothing more than this small plastic sign. How could the memory of Mary Ann Girling and her Shakers have vanished so completely? Surely it is no coincidence that just a few fields away, that conspiratorial tower rises over the trees, wreathed in its own dumb mystery. But as I look around me, the bare grass of the quiet Hampshire churchyard gives nothing away.

The facts of Mary Ann’s early life are equally unrevealing. She was born on 27 April 1827 in a cottage at Little Glemham, a village in rural Suffolk, between Woodbridge and Aldeburgh. It is a faintly threatening landscape of corn fields and black crows, often over-lowered by rain clouds which sweep in from the east, streaking downwards as if to suck water from the sea and unload it over the unsuspecting countryside. Mary Ann’s family, the Cloutings, lived in a cottage on Tinkerbrook Lane, an undulating country road now empty of the slate-roofed cottages which once lined it, long since consumed by the expanding fields of modern farming. But it is still bounded on one side by the estate and substantial brick mansion of Glemham Hall, and on the other by the river Alde, which widens into marshland before it reaches the sea at Aldeburgh. There, on a shingle spit, stands a pillbox-like Martello tower – the northernmost link in a chain to defend against Napoleonic invasion which stretched along the shape-changing Orford Ness and down the English coast as far as Hampshire. In Mary Ann’s time, the houses of the fishing village of Slaughden clustered round the tower; but like its outer defences, they were long ago lost to the grey-brown waters of the German Sea.

Both Constable and Turner painted this watery landscape, but in the early nineteenth century the lives of Suffolk’s ‘wild amphibious race’ were also recorded by the ‘poet of the poor’, George Crabbe, whose verse discerned the grimness as well as the beauty of this countryside and its people. Crabbe practised as a surgeon in Aldeburgh, and was addicted to opium, but later became a curate and preached in Little Glemham’s parish church, St Andrew’s, its characteristic Suffolk flint-knapped square tower rising over the land and its porch painted in gothic letters, enjoining worshippers, ‘This is the Gate of the Lord’. Inside, a neo-classical chapel and a white marble statue still bear testament to the master of Glemham Hall, Dudley North, Crabbe’s patron. Crabbe made his name in London with the help of friends such as Edmund Burke and Charles Fox; but in 1810 he wrote The Borough, and its tale of ‘an old fisherman of Aldborough, while Mr Crabbe was practising there as a surgeon. He had a succession of apprentices from London, and a certain sum with each. As the boys all disappeared under circumstances of strong suspicion, the man was warned by some of the principal inhabitants, that if another followed in like manner, he should certainly be charged with murder’. The story of Peter Grimes – who, it was implied, violated his charges – would provide Benjamin Britten with his opera. Its author – whom the Cloutings may well have heard preach in St Andrew’s – died in 1832, leaving his son, John, to become vicar of Little Glemham in 1840.

Like the New Forest, this corner of England has its own peculiarities. Its bleak, rattling coast stretches from Lowestoft to Felixstowe, passing the drowned churches of Dunwich and the ominous concrete bulk of Sizewell’s nuclear reactor which towers over black clapboard cottages that look as though they were painted with pitch. In Mary Ann’s day, the landscape was studded with windmills and church towers, a scene described by M. R. James in ‘A Warning to the Curious’: ‘Marshes intersected by dykes to the south, recalling the early chapters of Great Expectations; flat fields to the north, merging into heath; heath, fire woods, and above all, gorse, inland’. James’ eerie story, ‘Oh, Whistle, and I’ll come to you, My Lad’ – with its ghastly pursuer on the beach, ‘a figure in pale, fluttering draperies, ill-defined’ – was set on this coastline; Dickens’ collaborator, Wilkie Collins, another writer of mysteries, used Aldeburgh for his novel, No Name. And up the river Deben at Woodbridge, Edward FitzGerald, translator of The Rubiyat of Omar Khayyám, lived as an eccentric recluse, sailing his yacht in a white feather boa, eating a vegetarian diet, and mourning the death of his young friend, William Browne.

Parts of the Suffolk coast remain the least populated in southern England, yet its emptiness is as deceptive as the New Forest’s heath. In 1827, the year in which Mary Ann was born, ‘seven or eight gentlemen from London’ descended on the burial mounds at Snape, taking ‘quantities of gold rings, brooches, chains, etc’ away after their excavations; a century later, in the 1930s, a Saxon treasure trove would be discovered at Sutton Hoo, on the outskirts of Woodbridge. More recently, a mysterious circle of upturned oaks, reaching down to the watery otherworld of the ancient Britons, was found on the shore. Later, medieval Christianity produced its prophets: Julian of Norwich, the mystic and anchoress who endured ‘showings’ in 1370; and Margery Kempe of Kings Lynn who, thirty years later, was inspired by visions to renounce the marital bed, fine clothes and meat for communion with Christ. Modern science would discern other symptoms in these phenomena, but to the faithful of the fourteenth century, they were signs of a metaphysical universe.

They may have been lowly, but the Cloutings could trace their Suffolk roots back to the age of Julian of Norwich, when Wilmo Clouting was born, in 1327. In the five hundred years since, the family had barely moved fifteen miles, from the villages of Laxfield, Stradbroke and Saxmundham, to Orford – where Mary Ann’s grandfather, William, was born in 1760 – then inland to Little Glemham, where her father, also named William, was born in 1804.

Born before Victoria ascended the throne, Mary Ann came into a very different world to the one she would leave six decades later. ‘It was only yesterday, but what a gulf between now and then’, wrote William Makepeace Thackeray in 1860, looking back on his childhood. ‘Then was the old world. Stage-coaches … highwaymen, Druids, Ancient Britons … all these belong to the old period … We who lived before railways and survive out of the ancient world, are like Father Noah and his family out of the Ark.’ This often flooded corner of England was a remote, self-sufficient community in which lives were lived within themselves, as the reiteration of Suffolk surnames entered in the census and carved on village tombstones –...