![]()

CHAPTER 1

BRIBERY AND CORRUPTION TODAY: PRACTICES AND CHALLENGES

Fabian M. Teichmann and Bruno S. Sergi

Thanks to non-governmental organisations, corruption has been widely investigated both in the media and by researchers. One prominent contributor is Berlin-based Transparency International, founded in 1993 and renowned for its activities in combatting and statistically monitoring corruption. Both grand and petty corruption are considered major obstacles to sound policy-making and economic growth. We agree with this widely held, though not unanimous, view. Yet until the end of the 1990s, paying a bribe to a public official was still considered normal and acceptable behaviour in many parts the world. For example, some facilitation payments (meant to ‘facilitate’ transactions) were tax-deductible in Germany.1 Despite facilitation payments being outlawed in most countries since the late 1990s, bribes are still unofficially demanded by public officials in certain countries.

Recent history indicates that bribing (foreign) public officials has been particularly prevalent among multinational corporations. The large size and complexity of public investments offers the necessary cover for corrupt projects and allows foreign public officials to maximise their utility. Multinational corporations have often accepted these conditions and adapted to them by paying bribes. According to a 2013 report by Ernst & Young,2 nearly half of workers across Europe, the Middle East, Africa and India think bribery and corruption are ‘acceptable ways’ to survive an economic downturn, particularly where the receiving party has discretionary power, both parties expect economic rents and the transaction takes place in a weak institutional environment. (Table 1.1, Table 1.2)

Table 1.1. Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index.

Country | Rank | Corruption Perceptions Index |

France | 23 | 70 |

Portugal | 29 | 63 |

Rwanda | 48 | 55 |

Italy | 54 | 50 |

Oman | 68 | 44 |

South Africa | 71 | 43 |

India | 81 | 40 |

Iraq | 169 | 18 |

Syria | 178 | 14 |

GLOBAL AVERAGE 2017 | 43.07 |

Source: https://www.transparency.org/research

Table 1.2. Key Public Sector Institutions Seen as Corrupt.

Public Sector Institutions | Saying ‘Most’ or ‘All’ Are[…] |

Police | 36% |

Elected representatives | 36% |

Government officials | 35% |

Business executives | 34% |

Local government | 33% |

Prime Minister/President | 32% |

Tax officials | 32% |

Judges and magistrates | 30% |

Religious leaders | 18% |

Source: https://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/publication/people_and_corruption_citizens_voices_from_around_the_world

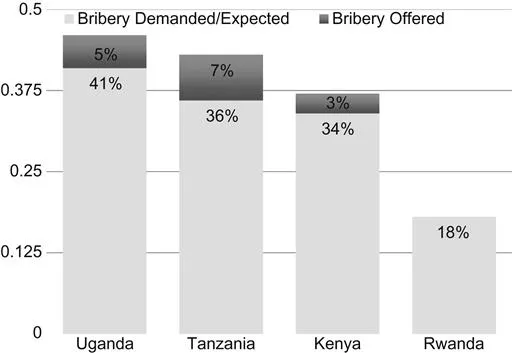

Today, corruption is still a problem both locally and worldwide, albeit to varying degrees. Affecting both developed and developing countries, corruption can be seen in a wide variety of nations at dissimilar stages of economic development and under various economic and political systems. According to the EU Commissioner for Home Affairs, an estimated 荤120 billion is lost to corruption annually throughout EU member states.3 The global cost is even higher. For instance, the cost of achieving the UN Millennium Development Goal on water and sanitation is increased by US$48 billion due to bribery.4 (Figure 1.1)

Figure 1.1. Citizens’ Experiences With Bribery EABI 2017. Bribery Demanded/Expected; Bribery Offered. Source: https://tikenya.org/east-african-bribery-index/

While statistical evidence supports the ongoing existence of the phenomenon, it is very difficult to determine its causes. Corruption seems most common in environments characterised by institutional inefficiency and weak private property rights. Capital-intensive natural resources, centralisation, reputation, history and levels of political competition all seem to be additional determining factors.

Furthermore, ‘soft’ factors, such as ethical failings or a lack of women in leadership roles, have also been associated with higher levels of corruption. However, evidence on women’s roles and bribery levels is inconclusive: for example, while women are commonly found in leadership roles in India, Ukraine and Russia, corruption levels remain extraordinarily high in these countries.

Multiple strategies to eliminate bribery have been considered, including increasing public debate and audit intensity. Others believe that paying commissions or higher wages to civil servants and fostering both freedom of the press and transparency within legal, administrative and electoral systems may also form part of the solution. Many past propositions, such as the idea that merely prosecuting money launderers would make it intolerable to use the proceeds of corruption, have proven ineffective since they can easily be circumvented, as will be illustrated below. Indeed, it might be concluded that, while many approaches towards eliminating bribery have been investigated, it seems to remain a predominant form of occupational fraud. Palpably, the proposed solutions have often failed.

It might also be inferred from experience that tackling corruption requires an interdisciplinary and transnational course of action. Despite widespread agreement that society could experience forms of renewal through removing corruption and prohibiting bribery, these phenomena are entrenched in various countries. It would be expedient to first analyse which attempted solutions have proved ineffective before then advancing alternative means of preventing bribery in multinational corporations. Thus, we will begin by examining four conventional approaches – legal, ethical, market-based and organisational – towards eliminating bribery.

CAUSES: AN INTRODUCTORY NOTE ON BRIBERY AND ITS ROOTS

Many theoretical approaches could be used to disentangle bribery in multinational corporations. Agency theory is particularly helpful, since it assumes that humans are self-interested and that ‘principals’ and ‘agents’ have differing interests. Here, we consider shareholders and board members as ‘principals’ and all other employees as ‘agents’.

Relationships between principals and agents are often considered problematic since the former bear responsibility for the outcome of tasks delegated to the latter, which is particularly challenging if an agent is unsupervised, since they might shirk or use the corporation’s resources for their own benefit, for example. In multinational corporations, ‘principals’ face the negative outcomes of acts of bribery. If the company is fined by regulators, shareholders’ entire investments and the positions of senior management may be jeopardised. Agents often face less risk since they typically do not hold shares in the company and often live in countries that allow them to evade law enforcement. Paradoxically, until their bribery is discovered, culpable employees often receive bonus payments for increased sales or performance resulting from their unlawful acts. Principals do not usually benefit to the same extent from bribery, and could simply buy stock options instead of shares if they wanted to increase their portfolio risk.

Agents wish to be compensated for acting in their principal’s best interests. This does not occur if the principal is interested in both productivity and compliance but only pays agents in relation to the former. Hence, linking an anti-bribery programme to an incentive system could arguably have the potential to prevent employees from shifting the majority of the risk onto the owners. Apparently, internal audits and control mechanisms should be used simultaneously to address agency problems. While incentive systems should continue to be tied to employees’ productivity, control of agents may be increased by introducing incentives for anti-bribery whistle-blowing. Agents could supervise one another and receive a bonus if they report an act of bribery.

As noted earlier, bribery continues to be prevalent in many countries: as illustrated in the Corruption Perception Index, it is commonplace in large parts of Eastern Europe, Africa and Asia. It also persists in the so-called Western world; one can frequently read about bribery scandals in many advanced Western countries. This is sometimes due to cultural reasons. For instance, corruption has been thoroughly evidenced in multiple judicial systems, which are characterised by judges demanding bribes. In affected countries, judges have often had to bribe commissions to be appointed to the judiciary. It is only natural for such judges to be both open-minded towards bribes and keen to recoup the money they spent to gain their position.

Many observers suggest that the chances of being caught and punished are rather low. Corrupt public officials rarely suffer the consequences of taking bribes. Hence, the expected utility of this unlawful act continues to be high, with disproportionate benefits from taking bribes and very low risk of being caught.

It is often argued that public officials’ salaries remain extraordinarily low in some countries, such as Ukraine or Moldova. Hence, they often need to take bribes to be able to finance reasonable living standards and manage their workloads. For instance, with regard to the latter, Eastern European judges frequently pay unofficial, additional salaries to professional staff members in their offices.

THE COSTS OF CORRUPTION

The deleterious consequences of corruption can be analysed on three levels:

- It can affect entire countries and have devastating effects on the public sector.

- It can inflict risks on private businesses.

- It can harm private citizens.

Corruption concerns both international and domestic policy-makers due to its many adverse effects on a country’s development. It is known to negatively impact a country’s efficiency, justice and legitimation of state activities, and to benefit a few at the expense of entire communities. Furthermore, corruption diverts public funds and fosters both inefficient use of resources and unfair income redistribution. Elevated levels of bribery discourage legitimate private business investments and inward foreign direct investment by increasing arbitrariness and reducing transparency. Hence, eliminating bribery is desirable from not only a legal but also an ethical perspective.

For multinational corporations, the excessive risks and uncertainty associated with corruption are partly related to the secrecy required to avoid detection, which may restrict the enforceability of agreements. For instance, multinational corporations could pay bribes but ultimately receive nothing in exchange if the receiving party does not feel bound to the deal; or they might encounter difficulties enforcing an entirely legitimate contract (not secured through a bribe) due to judicial corruption. At firm level, corruption may lead a company to become involved with, or otherwise be connected to, organised crime, partly because it can be challenging to distinguish corruption from business and politics in certain countries. Hence, tolerating corruption in multinational corporations can induce a corporate attitude that embraces criminal behaviour.

These negative consequences of corruption can cause frustration, unstable socio-political situations, and a lack of contentment among private citizens. Corruption tends to negatively affect people’s trust in government or management and can even lead to the collapse of political regimes or, in less stable countries, the loss of confidence in democracy itself. Unquestionably, corruption has overwhelmingly negative consequences, which is why various approaches have been undertaken with the aim of eliminating bribery.

Corruption might appear to generate some relatively positive consequences, such as an (temporary) increase in the efficiency of underpaid public servants, more significant willingness for compromise among politicians in challenging situations, and accelerated policy-making in certain circumstances; moreover, its negative relationship with growth might not hold true on a firm-level analysis. Nonetheless, its effects are found to be fundamentally contrary. For instance, while bribery might positively impact projects undertaken in a certain country and enable those without access to a strong network to make use of certain resources, it can also distort the prioritisation of projects and sacrifice greater goods for small benefits; this seems particularly apparent in less developed and emerging countries.

LEGAL ENVIRONMENT: THE OECD ANTI-BRIBERY CONVENTION

Devised by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions (hereafter, the ‘OECD Anti-Bribery Convention’) was adopted on 21 November 1997 and entered into force on 15 February 1999. It has since been supplemented on several occasions, including through the Principles for Managing Ethics in the Public Service (1998) and the Guidelines for Managing Confl...