![]()

1

The power of the dead in classical Sparta: The case of Thermopylae1

Polly Low

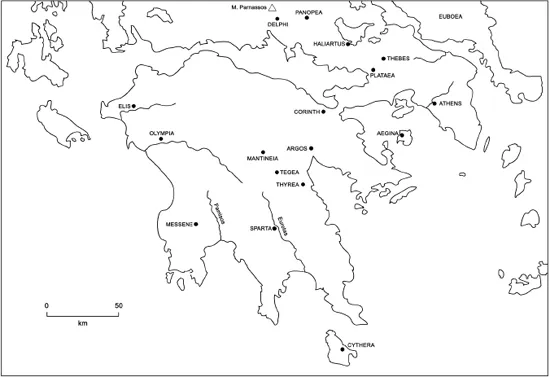

The battle of Thermopylae, in 480 BC, was an atypical event in Spartan history – a conflict fought far beyond Sparta’s normal sphere of influence or interest, at unusually uneven odds, and with an uncharacteristically (if not uniquely) lethal outcome: the remnants of a small Greek force consisting most famously (though not exclusively) of 300 Spartan citizens fought to the death in an attempt to thwart, or at least delay, the southward progress of a massive invading Persian army (Fig. 1.1). The afterlife of the battle is no less striking: the modern obsession with the event stretches back at least as far as the mid-eighteenth century (Macgregor Morris 2000), and its portrayal as a ‘battle that changed the world’ is still a prominent theme in contemporary scholarship (Cartledge 2006). As this chapter will attempt to show, this fascination is not purely a modern phenomenon. The battle of Thermopylae and the dead of Thermopylae occupy an unusually prominent position in the Spartan commemorative landscape throughout the classical period (480–323 BC), and beyond. Exploring the origins, changing shape, and wider implications of that prominent position is one of the chief concerns of this chapter.

But there is always a danger of making an unusual phenomenon into a unique and isolated one, and another, equally important, aim of this chapter is to show how the commemoration of the battle and its dead fits into the larger picture of Spartan funerary and commemorative practice. When seen as a whole, the commemoration of Thermopylae is certainly out of the ordinary in both form and scale, but its constituent elements are not entirely revolutionary. By placing this particular set of commemorative actions in their wider context, it is possible to say more (or at least to ask more questions) both about the reaction to Thermopylae, and about Spartan attitudes to burial, commemoration and monumentality at a more general level.

An important disclaimer must be made before proceeding any further. The evidence for classical Spartan commemorative practice, in general, and the commemoration of Thermopylae, in particular, is elusive in the extreme. A good deal of what follows is therefore devoted to the rather mundane task of attempting to unravel the matted clump of material which relates to the nature and location of some of the Spartan monuments and commemorative events associated with the battle and its dead. Even so, muchremains extremely unclear, and a good deal of what is said here should be counted as extremely speculative. I would argue, however, that such speculation is nevertheless worthwhile, not least because it forces the questioning of a tendency, which stretches back at least as far as the late fifth-century BC (Thucydides 1.10), to claim that the Spartans had no interest in constructing the sort of ideologically or emotionally charged monumental landscapes that were characteristic of other Greek poleis.

Thermopylae and its dead

Only one thing is known for certain about the immediate fate of the Spartans who died at Thermopylae: ‘they were buried on the spot where they fell, and a memorial was set up there to them’ (Herodotus 7.228). This memorial included the epigram, attributed to the contemporary poet Simonides, which famously summed up the paradigmatically Spartan qualities of single-minded duty and patriotism up to and beyond the point of death in the service of the city: ‘Foreigner, go tell the Spartans that we lie here obedient to their commands.’

Even this description is not entirely unproblematic. There is, for example, no obvious answer to the question of how exactly the burial was arranged. There were no Spartans left to look after their own dead, and the victorious Persians, far from being interested in following the usual Greek custom of allowing burial to a defeated enemy, went so far (according to Herodotus 7.238) as to mutilate the corpse of the Spartan king Leonidas. But even if the passage of the Spartan dead from battlefield to grave was probably a slower and more complicated process than Herodotus’ brief notice suggests (Wade-Gery (1933, 72) argues for a gap of at least eighteen months between battle and burial) there is no reason to doubt the basic veracity of the story. Burial and commemoration at or near the site of the battle was standard Spartan practice (Pritchett 1985, 243–6) and Herodotus’ description of the memorial is consistent with (though not identical to) the version later provided by Strabo (9.4.16; see Clairmont 1983, 223).

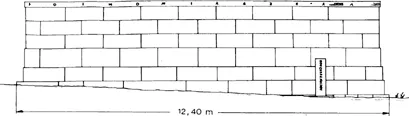

Up to this point, the treatment accorded to the dead of Thermopylae does not differ significantly from that which would be expected for the dead of any Greek battle, and their commemoration is comparable to that which the Spartans are known to have provided for their own dead elsewhere – the best-preserved example being the monumental grave constructed in the Athenian Kerameikos for those Spartans killed in the fighting in Athens in 404/3 BC (Fig. 1.2; Willemsen 1977).

The first hint at the existence of a more elaborate or sustained approach to the commemoration of the battle comes in Herodotus’ (7.224.1) claim to have found out the names of all the Spartans killed at Thermopylae:

Leonidas, proving himself extremely valiant, fell in that struggle and with him other famous Spartans, whose names I have found out, since they were worthy men. Indeed, I have discovered the names of all three hundred.

Herodotus does not say how he came to discover this information, but, if it is safe to assume this claim to knowledge is not a bluff, then there seem to be two main possibilities: either he saw the names written on a commemorative stele (whether at Thermopylae or, perhaps more plausibly, at Sparta; see below pp. 5–6), or the list of names had become part of the oral tradition of the Spartans. These two options are not mutually exclusive: it is possible to hypothesise for Sparta (as for Athens (Ebbott 2000, 93–94)) a scenario in which oral performance of inscribed names formed a key part of a the preservation and cultivation of collective memory. The fact that Herodotus was able to discover these names might, therefore, point towards the existence of some sort of deliberate commemorative effort, focussed on the preservation of the memory of all those (not just the axioi, the ‘worthy’ or famous) who fought and died in 480 BC (Ball 1976).

Stronger evidence for the existence of a commemorative festival for the dead of Thermopylae comes in a fragment of Simonides (fr. 531) reported by Diodorus (11.11.6):

Of those who perished at Thermopylae

All glorious is the fortune, fair the doom;

Their grave’s an altar, ceaseless memory’s theirs

Instead of lamentation, and their fate

Is chant of praise. Such winding-sheet as this

Nor mould nor all-consuming time shall waste.

This sepulchre of valiant men has taken

The fair renown of Hellas for its inmate.

And witness is Leonidas, once king

Of Sparta, who hath left behind a crown

Of valour mighty and undying fame.

Much is unclear about the form and purpose of this poem. The scale of the original work is unknown; it is possible that this passage formed only a part of a (perhaps much) longer piece (Flower 1998, 369). More importantly for the purpose of this discussion, there is considerable uncertainty as to the context which should be reconstructed for the poem’s performance. It is not impossible that the work was intended for private,relatively informal performance, perhaps in the context of a symposium or (in Sparta) syssition (Podlecki 1968, 258–262). It seems more likely, however, that the poem was delivered (at least initially) in a more formal, civic context; the reference to ‘this sepulchre’ (sekos) implies that the poem was intended to be delivered at or near some form of shrine commemorating the dead of the battle (Flower 1998, 369; Molyneux 1992, 186). If this reading is correct, an obvious question follows: where was that shrine (and the commemorative festivals associated with it) located?

The possibility that some sort commemorative activity was focussed on the site of the battle (and burial) cannot be ruled out. But if such commemorations did take place, then it is striking that they – unlike, for example, the commemorations centred on the other major land-battle of the Persian Wars, the Battle of Plataea (Jung 2006, 225–297) – have left almost no trace in either the archaeological or literary record. Later sources suggest that Thermopylae retained its importance for the Locrians (Strabo 9.4.2), and perhaps also the Thespians (Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. Thespeia), but later Spartan commemorative activity at the site is invisible, an absence which is all the more notable given Sparta’s interests in the region in later years (most apparent in her efforts in the 420s BC to establish a colony at Heraclea Trachinia; see Thucydides 3.92–3). Simonides’ poem seems to fit that general pattern of Spartan disengagement from the physical site of the battle. The fact that the location of the battle needs to be specified by name implies that the poem is being delivered somewhere else, perhaps at a panhellenic sanctuary or at Sparta itself (Bowra 1933, 279). Indeed, as Steiner (1999) persuasively argues, the poem as a whole can be seen as a representation or exploration of the consequences of commemorating the dead in a location that is distant from their physical remains. The tomb itself is replaced by the altar and, by extension, the commemorative festival which is centred on it. Physical markers of grieving and bereavement – the winding-sheet, the ritual lament – are overshadowed by rituals of praise and glory, and mourning for the dead is supplanted by praise and exhortation, ‘transmuting grief into celebration’ (Steiner 1999, 392).

This theme of the separation of commemoration from the physical remains of the dead can be pursued, and tied more closely to commemoration within Sparta itself, by turning to a much later piece of evidence: a brief comment made by the geographer Pausanias (3.14.1, late second century AD) in the course of his description of the monuments of central Sparta:

Opposite the theatre are two tombs; the first is that of Pausanias, the general at Plataea, the second is that of Leonidas. Every year they deliver speeches over them, and hold a contest in which none may compete except Spartans. The bones of Leonidas were taken by Pausanias from Thermopylae forty years after the battle. There is set up a slab with the names, and their fathers’ names, of those who endured the fight at Thermopylae against the Persians.

Pausanias’ comments must, for obvious reasons, be treated with caution as evidence for the form (or even existence) of these monuments in the classical period (and there are, as will be discussed below, p. 8, specific problems with his account of the return of Leonidas’ remains). Nevertheless, his reference to the existence of a stele listing the names of the Three Hundred does deserve some attention.

It is tempting to assume that the list of names Pausanias reports seeing must be a fifth-century BC monument (perhaps even the source of Herodotus’ information; see above p. 3). However it is equally, perhaps more, likely that this stele was a later construction: the Roman-era fascination with the Persian Wars in general is well documented (Alcock 2002, 74–86), while a specific interest in lists of the dead is also now becoming apparent (a stele apparently listing the names of the Athenian dead of Marathon has recently been found at the villa of Herodes Atticus in Arcadia, although full details of the inscription (SEG 41.425) have not yet been published). But even if the list seen by Pausanias were not original, the fact that such a list existed (or could be created) so long after the battle must be significant, and gives further, albeit still circumstantial, support to the theory (outlined above) that deliberate effort was invested in remembering the names of the dead of Thermopylae.

More significantly, the existence of such a list supports the view that the commemoration of the battle allowed space for the remembering both of the collective – the ‘Three Hundred’ as a distinct and special group – and of the individuals who made up that collective. And – in a Spartan context – it is precisely this combination of collective and individualising commemoration which marks the treatment of the dead of Thermopylae as something unusual. Commemoration, in Sparta, of individual Spartan war dead is well attested: both literary (Plutarch, Lycurgus 27.1–2, Moralia 238d) and epigraphic evidence reveals that those who died in war were allowed an inscribed memorial in Sparta. But these monuments were irregular, scattered and probably associated with private or family commemoration. Where the Spartans are seen providing civic, collective commemoration to their war-dead, the memorials seem to focus, precisely, on the collective: the dead of the ‘Battle of the Champions’, for example, were reportedly commemorated with hymns sung at the annual Spartan ‘festival of the naked youths’ or Gymnopaedia (the testimonia, all late, are collected by Pettersson 1992, 43), but these dead are an anonymous mass – any scope for commemorating an individual has been effaced. Although, therefore, the scope for individualisation allowed by a simple list of names might...