eBook - ePub

The Secret Museum

About this book

The Secret Museum is a unique treasure trove of the most intriguing artifacts hidden away in museum archives from all over the world – curated, brought to light, and brought to life by Molly Oldfield in a beautifully illustrated collection.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art General

GOING BEHIND THE SCENES AT the museum devoted to the genius of Roald Dahl, I felt a little like Charlie Bucket must have felt, clutching his golden ticket as he walked through the wrought-iron gates of the factory belonging to confectionary wizard Willy Wonka.

Famously, Roald Dahl wrote in a writing hut, which he called his ‘nest’ or ‘womb’, in the garden of his home, Gypsy House, in Great Missenden, a pretty village in Buckinghamshire. Every morning, Dahl would wander out of his house, across the garden, and go through a yellow door into his hut. Inside, he had everything just the way he liked it. He sat in a wingback chair, which had been his mother’s and placed a specially made writing table covered in a green billiard-table cover over his knees, just so.

He had a heater taped to the ceiling in the winter and covered the windows throughout the year – one with a shower curtain, the other with curtains in a fabric covered in blackbirds. On the walls he taped letters from his family and other things he loved. On a low table to his right he kept curious objects – a metallic ball made up of crushed silver chocolate-wrapping paper, a cuneiform tablet and his own invention, the ‘Wade-Dahl-Til1’ (or WDT) valve.

When Dahl was living in New York, his son, Theo, was out in his pram, being pushed along by his nanny, when a taxi hit him. His skull was shattered and he started to go blind because of fluid on his brain. Dahl contacted Stanley Wade, a hydraulic engineer and Kenneth Till, a neurosurgeon. Dahl loved knowing what made things tick, had experienced brain injury first hand, and he imagined that, as a threesome, they could come up with something truly brilliant. The trio invented the WDT valve to help Dahl’s son recover. Three thousand children around the world were helped by their invention.

Also on the table, right beside his chair, he kept a mug containing six trusty yellow HB pencils and, above them, stuck to the wall, an electric pencil sharpener. He wrote with the pencils each day, on yellow A4 paper imported from America. As he wrote, Dahl stored everything – letters, notebooks, first, second and third drafts – in order, neatly tucked away inside his hut.

When the Roald Dahl Museum opened in the village just down the road from Dahl’s house, all of these letters, notebooks and drafts of stories were moved to the museum. They are kept under lock and key in a small room, next to the museum archivist’s desk. I went to have a look.

To get to the archive I went up some stairs leading off the courtyard of the museum. As the archivist unlocked the door, I looked out of the window of her office, down into a room of the museum below. It was filled with giggling children, and images of Dahl’s creations.

We stepped inside the room, filled with row upon row of grey boxes. Inside each box are piles of letters, photographs and drafts of stories, in which each of these creations was brought to life, with HB pencil, on that imported yellow paper.

The seeds of some ideas live in the pages of Dahl’s notebooks, two of which I saw. Each one is red, with the word ‘Masterpiece’ embossed on the cover. The books are filled with one- or two-line pencil scribbles: ‘a pale grey face like a bowl of porridge’, ‘a woman with one large muscular calf. What does this denote?’ and ‘man in bathtub using kite to channel electricity’. Each thought shimmers with potential.

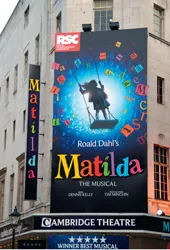

Some stayed in the notebook, while others were developed into stories, for instance, The BFG. I saw the moment Dahl thought of the character: he wrote the letters of the giant’s name in one of the notebooks and circled them. Indeed Matilda had been in his ideas book for 20 years before he began to write about her.

Each story took a while to get right. In an early draft of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, the Oompa Loompas were called Whipple-scrumpets. At first the BFG befriends a boy named Jody, rather than a tiny girl named Sophie who saw the giant at her window, catching dreams.

I pulled down the Matilda box because I was curious to see how that tale had evolved. I read through Draft 1. The story was called ‘The Miracle Child’, and Chapter 1 was called ‘Wickedness’. In this first version, handwritten by Dahl in 1986, ‘Matilda was born wicked and she stayed wicked no matter how hard her parents tried to make her good. She was just about the most wicked child in the world.’

Matilda plays the same tricks on her parents as she does in the published version, but her motivation is different: in the final draft she is trying to get her own back on her parents, who couldn’t give a stuff about her, whereas in the original draft she did these things simply because she was ‘wicked’.

The first draft is pretty short. There is hardly any mention of Miss Trunchball; Miss Honey is called Miss Hayes; and, at the end, Matilda dies. She discovers her magical powers – being able to move things with her eyes – in a class at school, and goes over to Miss Hayes’s house to investigate her new skills. On the way home to Matilda’s, she and her teacher see a car accident. Some children are trapped in a mini-bus, underneath a truck. With no time to lose Matilda lifts the truck off the mini-bus, using only the power of her eyes, and frees the trapped children. And then, exhausted from the effort, she dies.

It’s not the story of the unloved, imaginative girl rescued by an understanding adult that everyone loves today, and has a totally different ending. It took Roald Dahl ages to get the story he wanted to tell to come out right. He handed each draft of yellow papers to his secretary, Wendy. Then he’d annotate her typed pages and carry on. It wasn’t until Draft 6 that he was satisfied with Matilda. Perfection was a long process.

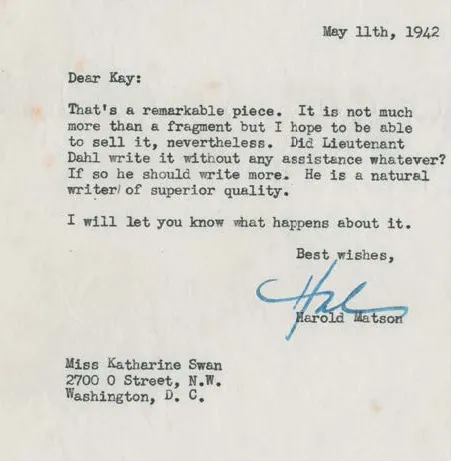

I wanted to know what the first item in the archive was, so I had a look and found a letter marked by the archivist as RDMSC RD 1/1/1. The letter is the first item in Dahl’s ‘Personal’ file. It was written by a New York literary agent, named Harold Matson, to Miss Katherine Swan, who was the writer C. S. Forester’s secretary. The letter tells an interesting story: the story of how Dahl became a writer.

The first story Roald Dahl ever wrote was a true one – which he embellished, with his nascent storytelling skills – about his time in the RAF in the 1940s. He was sent on a mission from Egypt to Libya. He hadn’t had much training, and on the final leg of the trip he crash-landed in the desert because he couldn’t see a runway, and was running out of fuel. He fractured his skull and nose and was unable to see. Luckily, a pilot called Peter had seen the plane coming down into the desert and rushed to the wreck to pull Dahl’s body out. Dahl carried on flying, but after severe headaches, a blackout and some time recovering in England he was transferred to an office job in Washington as an assistant air attache. On the first day of his new job, he was sitting at his desk wondering what on earth he was supposed to be doing when the writer C. S. Forester came in and asked him if he had any good stories about the war. America had just joined the Allies and the public was hungry to hear stories of heroic deeds.

Dahl and he got chatting, and Forester invited him out for lunch. They were so busy talking and eating that Forester forgot to take notes and so he asked Dahl if he would mind sending over some anecdotes about his crash in Libya, which Forester could then shape into a story. Dahl did so, but he wrote the story out in full. Forester thought the tale was brilliantly written and replied to Dahl with the life-changing question: ‘Did you know you were a writer?’

Forester sent the piece to his agent, Harold Matson, who then wrote this letter to Katherine Swan asking: ‘Did Lt. Dahl write it without any assistance whatever? If so, he should write more. He is a natural writer of superior quality.’ No wonder the letter is stored first in Dahl’s archives. I imagine it changed his life.

The second letter in the archives is Dahl’s reply to Matson, asking whether he’d like a piece about Greece. He asked to remain anonymous if his first story was published, as members of the RAF were not allowed to publish tales of the war. He also requested that if his writing was going to be illustrated, that the drawings of his plane be accurate. The next letter in the file is a reply from Matson saying that there was no problem about either anonymity or illustrations, and he had some good news: he’d sold the piece for £300.

It was published verbatim in August 1942 in the Saturday Evening Post. Dahl had called the story ‘A Piece of Cake’, but it was changed to ‘Shot Down over Libya’ to sound more dramatic. Dahl had changed details of the original story: being shot down made a better story than running out of fuel. Already Dahl’s love of exaggeration for the sake of a good story shone through. He continued to write, and Matson became his agent. Dahl told the whole story himself in ‘Lucky Break’.

Over his career Dahl wrote two novels, 19 short story collections, six film scripts, some television shows and a play. However, it was not until he moved to Buckinghamshire, asked a man named Wally Saunders (said to be the inspiration for the BFG) to build his hut and began writing fantastical children’s stories that his career really took off. How lucky that Forester popped in to meet Dahl, and Matson wrote this letter, number 1 in the archives, that set the wheel of stories, letters and ideas in motion.

His children’s stories are still loved by children of all ages. On my way from London to Buckinghamshire to visit the museum, I stopped for petrol. The Indian man at the till asked me:

‘Going anywhere nice today?’

I told him, ‘I’m going to the Roald Dahl Museum.’

‘Oh,’ he said, perking up. ‘I love that guy! I love his stories.’

‘So do I,’ I said. ‘Which is your favourite?’

‘Oh, the one with the boy who puts white powder in the drink.’

‘George’s Marvellous Medicine?’

‘That’s the one,’ he said, lifting his hands to the heavens and laughing. ‘That one could have me giggling all day.’

I told him, ‘I’m going to the Roald Dahl Museum.’

‘Oh,’ he said, perking up. ‘I love that guy! I love his stories.’

‘So do I,’ I said. ‘Which is your favourite?’

‘Oh, the one with the boy who puts white powder in the drink.’

‘George’s Marvellous Medicine?’

‘That’s the one,’ he said, lifting his hands to the heavens and laughing. ‘That one could have me giggling all day.’

[Matilda, the musical]

The first draft of Matilda, which I read at the museum, is a totally different story to the one everyone knows and loves today.

The first draft of Matilda, which I read at the museum, is a totally different story to the one everyone knows and loves today.

[Item 1/1/1]

I held it in my hand: the very letter that set Dahl on the path to being one of the world’s best-loved writers.

I held it in my hand: the very letter that set Dahl on the path to being one of the world’s best-loved writers.

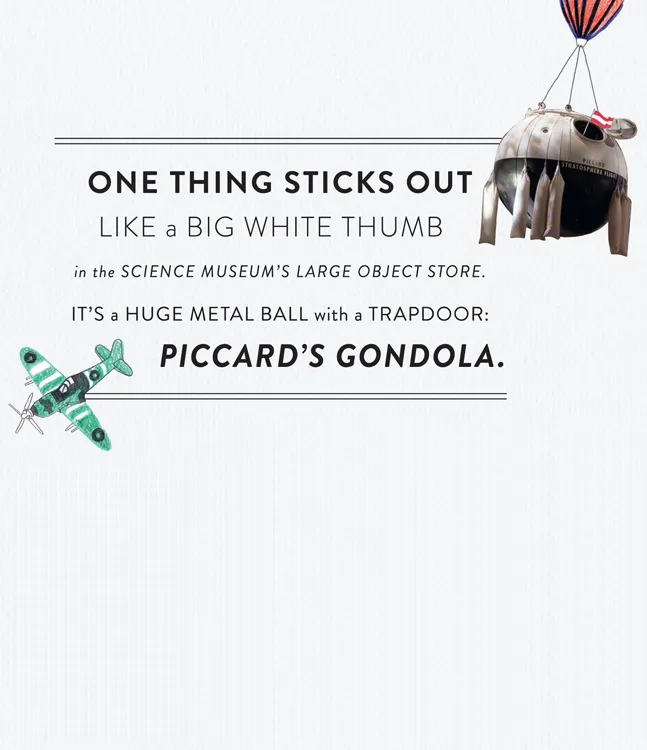

AUGUSTE PICCARD (1884–1962) WAS AN eccentric Belgian scientist. He was fascinated by the stratosphere – the layer of the atmosphere that begins 16 kilometres above where you are sitting now – and made this gondola to take him there. Using it like the basket of a hot air balloon, he attached it to a balloon filled with hydrogen and floated up miles into the sky. It’s amazing to stand in front of it and imagine Piccard climbing inside, shutting the door over his head and taking off.

Like many of the Science Museum’s large objects, Piccard’s gondola is stored in one of several aircraft hangars on an ex-RAF airfield in Wroughton, Wiltshire. It shares its berth with planes, including a Lockheed Constellation aircraft used to transport roadies and equipment on a Rolling Stones concert tour, and a very sleek plane designed by Burt Rutan (who also designed Voyager – the first plane to fly around the world without stopping for refuelling – as well as a hybrid flying car and space craft for Virgin Galactic). But the gondola has been higher than any of the aircraft in the hangars in Wroughton.

Piccard made his first trip to the stratosphere in 1931. He broke a world record for the highest any man had ever been and then crash-landed in Obergurgl, a little alpine town of 14 farms which, after a lifetime of sleepy obscurity, became known internationally when Piccard accidentally arrived. This gondola in the Science Museum’s behind-the-scenes collection was used for Piccard’s second journey to the stratosphere, when he reached 16,201 metres. He and his assistant took off one summer’s day in 1932, from just outside Zurich. The launch was filmed by a news team from Pathé and released under the title ‘10½ Miles Above the Earth! Professor Piccard and Dr Cosyns, safe & sound after world’s most daring & romantic scientific adventure’. In those days, science and adventure were still deemed to be ‘romantic’.

The newsreader says, in his old-fashioned broadcasting style, ‘The start was made at dawn from Diibendorf aerodrome near Zurich. The preparations for the flight began at midnight. And thousands of people had made the journey from Zurich in special trains, whilst a battalion of Swiss troops held down the guy ropes.’ He continues: ‘When all was ready he clambered inside the gondola, which contained a mass of scientific instruments, and gave the signal to let go. The balloon rose quickly and eventually climbed to over 10½ miles above earth. Just imagine – whilst we were sweltering in a heatwave, he was nearly frozen to death in 15 degrees Centigrade below zero.’ He ends: ‘From the practical point of view, Professor Piccard’s experiment is of the highest scientific importance. One of the things it will definitely do will be to enable better weather forecasts to be made, and won’t that be a boon when we are picking out our holidays!’

Watch the film online if you’d like to see Piccard leaning out of the gondola, waving goodbye with his hat in his hand. ‘Off we go into ze stratosphere,’ he seems to be saying (moustache blowing in ze wind).

Piccard was a funny-looking man. He had a bald head, with tufts of hair on e...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Dedication

- Introduction

- A GUTENBERG BIBLE ON VELLUM

- HARRISON SCHMITT’S SPACE SUIT

- THREE PIECES OF MARS

- A PIECE OF NEWTON’S APPLE TREE

- THE FIRST CULTIVATED PEARLS

- LAMOUROUXIA VISCOSA SEED FROM MEXICO

- THINGS BENEATH THE FLOORBOARDS

- A BEJEWELLED CROSS

- A HAIDA SHAMAN’S RATTLE

- FRANCIS CRICK’S SKETCH OF DNA

- TABLET K.143, SCHOOL EXERCISE BOOK OF ASHURBANIPAL, KING OF ASSYRIA

- VLADIMIR NABOKOV’S BUTTERFLY GENITALIA CABINET

- CHARLES DICKENS’S FELINE LETTER OPENER

- THE HEART TOKEN

- ITEM RDMSC RD 1/1/1

- AUGUSTE PICCARD’S BALLOON GONDOLA

- JASON JUNIOR

- UNDERWATER PAINTING BY ZARH PRITCHARD

- ANGLERFISH COUPLE

- THE FIRST GIRAFFE IN FRANCE

- A GREAT AUK EGG

- A GLASS JELLYFISH

- THE INTERIOR OF VASA

- FLAG FROM THE BATTLE OF TRAFALGAR

- A BLUE WHALE

- LOGBOOK OF THE KON-TIKI EXPEDITION

- WALLY HERBERT’S SLEDGE

- SONG 21

- EXU BOCA DE FOGO

- LIVINGSTONE AND STANLEY’S HATS

- HAWAI’IAN FEATHER HELMET

- THE LIENZO OF TLAPILTEPEC

- MIXTEC TURQUOISE MOSAIC SHIELD

- ALICIA (1965–67) MURAL BY JOAN MIRÓ AND JOSEP LLORÉNS ARTIGAS

- AN UNOPENED BOOK

- THE DIAMOND SUTRA

- TIBETAN ABBOT’S COSTUME

- TWO GOLDEN BEES, FROM THE GLASS PALACE IN BURMA

- SLAP-SOLED SHOES

- BLOOD’S DAGGER

- TELL HALAF SCULPTURES

- ALFRED NOBEL’S WILL

- SKETCHES OF CHURCHILL

- FRIENDSHIP BOOK

- TORAH ARK CURTAIN

- THE TOWER OF THE BLUE HORSES BY FRANZ MARC

- CHRISTMAS TELEGRAM FROM AGENT ZIGZAG

- A CHANNEL ISLANDS PILLAR BOX

- BUCKINGHAM PALACE SWITCHBOARD

- A LEAF OF GOAT EYE STAMPS

- THE TOOLS THAT BELONGED TO QUEEN VICTORIA’S DENTIST

- SKULL OF A TAPUIASAURUS MACEDOI

- HANDAXE FROM HOXEN

- A SERIES OF PAINTINGS BY OZIAS

- THE SPAULDING COLLECTION OF JAPANESE PRINTS

- VAN GOGH’S SKETCHBOOKS

- BOX IN A VALISE BY MARCEL DUCHAMP

- MARGARET FONTEYN’S TUTU

- STANLEY PEACH’S CENTRE COURT DESIGNS

- ORIGINAL DRAFT OF ‘AULD LANG SYNE’, ROBERT BURNS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- PICTURE CREDITS

- Copyright page

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Secret Museum by Molly Oldfield in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.