eBook - ePub

The Economics of Regional Security

NATO, the Mediterranean and Southern Africa

- 348 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Economics of Regional Security

NATO, the Mediterranean and Southern Africa

About this book

This important book explores the threats and challenges to regional security, for Nato, in the Mediterranean, and in the sub-Saharan countries, namely southern Africa. Written and edited by leading researchers, the volume's significance lies in its demonstration of how concepts from economics and other social science disciplines can be applied to important issues of defence, conflict and peace at the regional level.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

NATO

1 The economics of European defense procurement

Introduction

This chapter deals with two issues involving both Europe and NATO. First is the contribution of defense economics to policy formulation, focusing on choices, procurement policy, defense industries, and alternative industrial policies. The second concerns the economic implications of extending the Single European Market (SEM) to defense procurement. This involves a statement of the policy problem, consideration of alternative scenarios, an evaluation of collaboration, and the prospects for creating a European Union defense industrial base.

European and NATO defense equipment markets: the need for difficult choices

Defense policy has to respond to two pressures, namely, constant or falling defense budgets and equipment which is both costly and becoming costlier. For example, the four-nation Eurofighter combat aircraft is estimated to cost over £13 billion for total development and £40.2 million for unit production costs (1997–98 prices; see HCP 695, 1998). Moreover, equipment costs are rising so that on a unit for unit basis, new equipment costs far more than the equipment which it replaces. Typically, the unit production costs of equipment (combat aircraft, warships, missiles) have risen at some 10 percent per annum in real terms, resulting in a doubling in costs every 7.25 years (Kirkpatrick, 1995; Pugh, 1993). These cost increases reflect the technical arms race as a nation seeks superior equipment to its potential rivals, or tries to prevent its forces from falling into a position of inferiority. The result is “technical leapfrogging” reflected in improved performance and effectiveness of equipment, but such improvements are costly.

Rising unit costs and a limited defense budget mean that fewer units can be bought, with adverse impacts on the numerical strength of the armed forces and on the output of national defense industries. For example, in the UK the air force has declined from 5,213 aircraft in 1954 to 1,100 in 1994; and in the 1950s, 27 new types of aircraft were brought into service compared with only two new types in the 1990s (hence suggestions of a future consisting of a one tank army, a one ship navy and one Starship Enterprise air force; Kirkpatrick, 1997, p. 12). Various policy initiatives such as increased defense budgets, increased industrial productivity, and improvements in the efficiency of procurement policy can delay but not prevent the impact of rising unit costs (Pugh, 1993, pp. 181–182). Thus, for defense policymakers, rising unit equipment costs and constant or falling defense budgets mean that difficult choices cannot be avoided; and these choices have to be made where the future is unknown. Choices require sacrifices. The question is what to choose and what to sacrifice, and can economics help?

In making defense choices, two market developments cannot be ignored. First, the existence of excess capacity in the world’s defense industries. Second, the competitive threat from large US defense companies able to exploit economies of scale, learning, and scope, thereby offering modern equipment cheaply and quickly. These developments raise some difficult policy questions for European nations. Is it worth creating or retaining a national defense industrial base; is a European defense industrial base the solution and what might it look like; or should Europeans buy their equipment off-the-shelf from the US?

Changes since 1990: the stylized facts

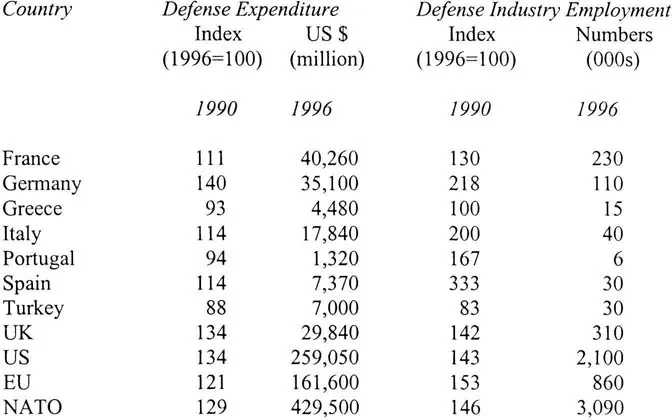

The trends in defense expenditure and defense industry employment within Europe and NATO over the period 1990–96 are shown in Table 1.1. Following the end of the cold war, there has been a general decline in both expenditure and industry employment with substantial reductions in Germany, the UK, and the US. Over the same period, real equipment expenditure fell by 15 percent in NATO Europe, by 23 percent in the US, and by 20 percent in NATO (SIPRI, 1998). Table 1.1 also shows major reductions in defense industry employment in Germany, Italy, and Spain. For defense industries, the cuts in defense spending have been reflected in cancellations, fewer new projects, smaller production runs, delays in ordering, the stretching out of programs, and a reduced demand for spares and support. Industry has responded with down-sizing, mergers, the search for new military and civil markets, and exits from the industry. But industrial restructuring has created two problems for policymakers. First, mergers make it increasingly difficult to maintain competition. Second, major gaps in ordering new equipment could mean the exit of key industrial capabilities from the national defense industrial base. This issue has arisen in the US in relation to the continued existence of the national defense industrial base for bomber aircraft, tanks, and nuclear-powered submarines. In this context, the relevant defense industrial base comprises prime contractors, sub-contractors, and suppliers (Hartley et al., 1997). Policymakers can respond by allowing market forces to work, or they can intervene by offering state support in the form of continued small-scale orders, mid-life up-dates, through technology demonstrators, or by funding the moth-balling of specialized plant and equipment. Each policy option needs to be evaluated in terms of its estimated costs, benefits, and risks (CBO, 1993).

Table 1.1 Defense expenditure and employment

Note

Expenditure data in millions of US $ at 1993 prices and exchange rates.

Source: BICC (1998).

The economics of defense procurement

Defense equipment markets bring together both procurement and defense industries representing the demand and supply sides of the market. The distinctive feature of defense procurement is the importance of government both as a major buyer and as a regulator. For some equipment, the government is a monopsony (e.g., nuclear systems), and as a regulator it can determine profits on defense contracts and whether to permit defense exports. The government can use its buying power to determine the size of the national defense industry, its structure, entry and exit conditions, industry conduct (e.g., R&D, advertising), and industry performance (e.g., pricing, profitability, technical progress, exports).

Equipment procurement involves a set of policy choices about what to buy, who to buy from, how to buy, and the choice criteria. Decisions are needed on the type of equipment to be purchased which will have an impact on technical progress, and choices are also required between air, land, and sea systems and between the quality and quantity of equipment. A contractor has to be chosen involving further choices about the method of selection (competition versus direct negotiation) and between domestic and foreign firms (i.e., entry conditions). A contract type has to be selected ranging between cost-plus, target-incentive, and fixed price contracts (determined by competition or direct negotiation). Finally, in selecting equipment, policymakers have to decide whether to choose on the basis of narrow defense criteria (e.g., equipment performance, price, delivery, and risk) or on the basis of wider economic, political, and social criteria (e.g., jobs, technology, exports, and support for national defense industrial base).

Choices and efficiency are central to economics and their application to defense and procurement policy suggests four guiding principles for defense policymakers faced with the need to make difficult choices:

• Final outputs. This suggests that policymakers should not focus on the numbers of aircraft, tanks, and warships which are inputs. Instead, the focus needs to be on the contribution of inputs to final output in the form of protection, security, crisis management and, ultimately, peace. Furthermore, the contribution of inputs to output needs to be evaluated on the basis of marginal costs and benefits.

• Substitution. This suggests that there are alternative methods of achieving protection. Within the equipment sphere there are possibilities of substitution between attack helicopters and tanks, between strike aircraft and ground forces, between cruise missiles and bomber aircraft, and between maritime patrol aircraft and frigates. Some of these substitutions have implications for the traditional monopoly property rights of each of the armed forces. For example, for air defense, army-operated surface-to-air missiles might replace manned fighter aircraft operated by the air force. Of course, in the private sector such substitutions are made in response to competition and the search for profits.

• Competition. This is a means of promoting efficiency. Here, there are opportunities for nations to open up their defense procurement markets to domestic and foreign competition. A further possibility would be to introduce competition for the life-cycle support of equipment. For example, private contractors could compete with the armed forces for the repair, support, and maintenance of equipment. A more radical possibility would be for firms to compete for the leasing of equipment, so that the armed forces would lease rather than own equipment, thereby transferring responsibility for maintenance from the armed forces to industry (compare car hire: but it is recognized that the leasing of defense equipment involves complex transaction costs for long-term contracts).

• Incentives. Military personnel and civil servants need employment contracts which provide incentives to economize and save when purchasing and using equipment. Problems arise because incentives are either lacking or are perverse. For example, on a one-for-one replacement basis, the armed forces often buy technically improved equipment for the benefits it offers to users without consideration of system-wide costs.

The economics of defense industries

Four economic features are important for understanding defense industries:

• The importance of R&D. The industry is characterized by high and increasing R&D costs. For example, development costs for the American F-22 Raptor combat aircraft have been estimated at almost $23 billion (1997 prices; CBO, 1997). As a result, it is important to spread such total fixed costs over a large output so as to reduce the unit costs of acquisition.

• The importance of quantity. Quantity is a major determinant of average costs through the spreading of fixed R&D costs and through lower unit production costs resulting from economies of scale and learning. For example, learning economies in the aerospace industry result in a reduction in unit production costs of about 10 percent for every doubling of cumulative output (Sandler and Hartley, 1995, p. 124).

• The competitiveness of the US defense industry. Large US defense companies able to achieve economies of learning, scale, and scope are a major competitive threat to European and other nations’ defense industries (see Table 1.2). The scale of re-structuring in the US has led to a reduction in the number of major American defense and aerospace companies from 15 in 1990 to 4 in 1998. At the same time, 6 European nations have three times as many firms as the US, supporting a total defense budget less than half that of the US (HCP 675, 1998, p. xiv).

Table 1.2 Leading aerospace companies, 1998

Note Since mid-1998 there has been further restructuring.

Source: Flight (1998).

• Defense industries as economically strategic industries. In addition to their traditional military-strategic significance, defense industries have the features of an economically strategic industry. Such industries are characterized by decreasing costs reflecting scale and learning economies, high technology reflecting major and costly R&D together with technical spill-overs to the rest of the economy, and by monopoly profits resulting from imperfect competition based on national monopolies and oligopolies (e.g., aerospace, electronics, nuclear). As a result, governments might support these industries as part of strategic trade policy (e.g., using subsidies and anti-competitive behavior) as a means of promoting spill-overs and obtaining a share of monopoly profits in world markets (e.g., Airbus).

Alternative industrial policies

The need for difficult choices resulting from rising equipment costs and falling defense budgets remains. Broadly, the policy options range from a review of defense commitments (e.g., abandoning a major commitment) to a review of the major spending areas, namely, equipment and personnel (e.g., use of reserves and contractors). A review of equipment raises the possibility of a radical review of procurement policy involving more competition and contractorization. A key policy question arises over continued support for a national defense industrial base. Is it worth paying the price of independence by buying from a national defense industrial base; why not shop around and buy equipment off-the-shelf from the cheapest suppliers in the world market? These questions are part of more general issues about alternative industrial policies.

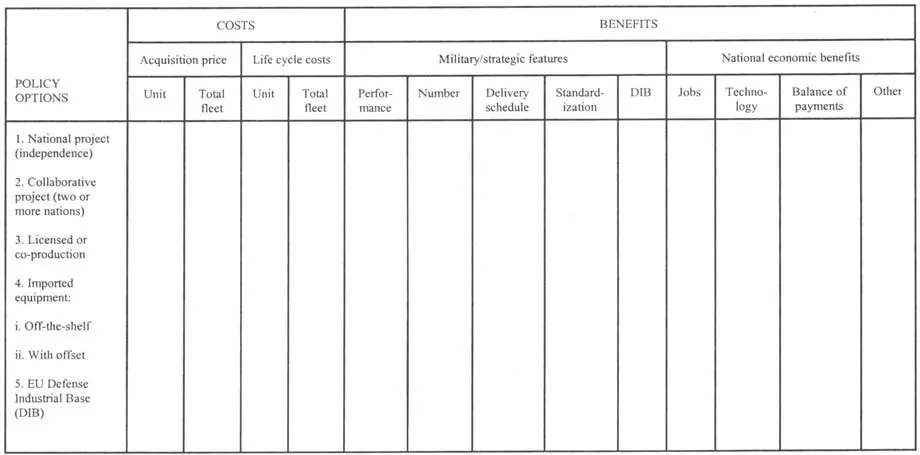

There are a variety of methods of purchasing defense equipment. These include support for a national defense industrial base, international collaboration (two or more nations sharing R&D and production), licensed or co-production, imports with or without offsets, and, for the European nations, the possible creation of a European defense industrial base. An economic evaluation of the costs and benefits of alternative industrial policies is needed. Such an evaluation would identify the objectives of policy and consider alternative methods of achieving these objectives, together with an assessment of their costs and benefits. Identifying policy objectives specifies the range of items to be included in the cost-benefit analysis. For example, will the analysis be restricted to military costs and benefits of equipment or will it include wider economic and industrial benefits? Similarly, if the objective is to retain a national defense industrial base, various alternative policies can be used such as ordering technology demonstrators, or dual-use purchasing, or allowing firms to bid for work usually undertaken in-house by the armed forces (contractorization). Table 1.3 presents a framework for evaluating the costs and benefits of procurement choices and the associated alternative industrial policies. Benefits distinguish between the military and strategic features of equipment and wider national and industrial benefits.

Table 1.3 Policy options: a framework for procurement choices

Procurement policy and its industrial aspects are often dominated by myths, emotion, and special pleading. There is scope for critical assessment: policies which appear attractive often have their limitations. Some examples are:

• Employment b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Figures and tables

- Introduction

- PART I. NATO

- PART II. THE MEDITERRANEAN

- PART III. SOUTHERN AFRICA

- Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Economics of Regional Security by Jurgen Brauer,Keith Hartley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.