1 The color orange in Yamagusuku Seichū’s Okinawan fiction

How did Okinawan fiction come to mean? What made this writing something other than a regional variation on the themes explored by contemporary authors of mainland Japanese fiction? To answer these questions, I begin by outlining in this chapter the conditions under which authors in Okinawa pursued their craft at the beginning of the twentieth century. Despite obstacles presented by the prefecture’s late entry into the nationstate, by the need to master standard Japanese, and by a shortage of venues for publication, authors in Okinawa duly impressed critics in Tokyo who prized local color. Yamagusuku Seichū, in particular, is noted for his skill in making Okinawa come alive through fiction. This he accomplishes through detailed descriptions of island life seasoned with dialogue inflected by local language. Yamagusuku’s success resulted in a boom in fiction-writing in the prefecture, where it also served as a model for subsequent generations of authors who sought to follow his lead in making the region speak through their creative expression.

“Local color,” a frequent topic in discussions of literary realism that took place in the USA at the turn of the century, was also a much-discussed phrase in Japan during the late Meiji period. In Japan, it referred less to the regional features of a work than it did to an assumption made by critics and readers of the (supposed) tie between author and birthplace. While some writers such as Tokuda Shūsei and Masamune Hakuchō disliked the hasty association readers often made between author and region, others welcomed it.1 As authors vied for recognition in the literary marketplace, this element naturally grew in importance. Aware of the cultural cachet gained by writers who integrated local color into their work, Yamagusuku made this feature a prominent one in his stories. Through the act of inscribing the climate and culture of Okinawa into prose, then a nascent form of writing in the region, Yamagusuku established himself as a pioneering author of Okinawan fiction. His writing also underscored the importance of native place literature (furusato bungaku) during this time. The origins of this literature lay in homeland art (heimatkunst; kyōdo geijutsu) first introduced, by way of Germany, to Japan in 1906. While this form of art featured descriptions with strong ethnic characteristics, over time it was reinterpreted as a literature of nostalgia (kyōshū).2 Bearing this reinterpretation in mind, I argue that Yamagusuku is important not only for creating a literary place by means of local color but also for throwing into sharp relief the idea of home as forever lost.

The color orange

In the Greek myth “Song of Philomela,” King Pandion’s daughter Philomela becomes the unwilling object of her brother-in-law King Tereus’ desires. After raping her, Tereus imprisons Philomela and cuts her tongue out to silence her. Despite this, Philomela weaves a tapestry in which she conveys to her sister Procne the details of Tereus’ crime. Seeking revenge, Procne kills Itys, her son by Tereus. She cooks and presents Itys to Tereus, who then eats his own son for dinner. When he discovers the sisters’ machinations, Tereus tries to kill the pair but to no avail. Amid his pursuit the three are transformed into birds: Tereus becomes a hoopoe, Procne, a swallow, and Philomela, a nightingale.

Classical authors as varied as Ovid, Spencer, Chaucer, and Milton have drawn upon this myth in their own creations, and modern and contemporary writers ranging from T. S. Eliot to Alice Walker have also found inspiration in the transformation of Philomela. While later versions differ from the Greek myth, all have in common the theme of beauty (the song of the nightingale) arising from destruction (the severing of Philomela’s tongue). For example, in The Color Purple, a contemporary twist of the classical myth, Walker alludes to Philomela as she tells the story of protagonist Celie’s rape and subjugation. Like her Greek counterpart, Celie has “no power of speech/To help her tell her wrongs. […]/ She had a loom to work with, and with purple/On a white background, wove her story in, Her story in and out.”3 In vibrant color, then, does Celie’s story emerge against the quilt’s monochrome background.

Little did mainland Japanese and Okinawan critics suspect that their desire for local color at the beginning of the twentieth century would result in the formation of Okinawan fiction, which was then and (I would maintain) now a distinct genre in Japanese letters. As we shall see throughout this book, stories written in response to cries for regional flourish did depict the flora, fauna, culture, and customs of Okinawa, in accordance with the critics’ demands. However, in addition to meeting these desiderata, prose fiction from Okinawa bore seeds of resistance, which, in the course of the century, alternately either threatened to erupt or simply lay dormant. Whereas mainland critics delighted in the superficial peculiarities of the region, its flora and fauna for example, local critics sought writing that probed deeper into the characteristics and issues of Okinawa. Naturally, these critics’ desire for authors to go beyond local color came into conflict with those who expected only a regional variation of a given literary theme in prose from Okinawa.

Well before debates on local color occurred in Okinawa, influential critics such as Tsubouchi Shōyō published literary criticism on how modern Japanese literature ought to be fashioned.4 Although the pursuit of origins continues, generally speaking, many literary critics tell us that they consider modern fiction in Japan to have been established by 1890 with the publication of works such as Futabatei Shimei’s The Drifting Cloud (Ukigumo, 1886–9) and Mori Ōgai’s “The Dancing Girl” (“Maihime,” 1890).5 What made this literature new, in part, was the language in which it was written. Futabatei and Ōgai put into practice Shōyō’s theory of modern fiction, which stated that a language different from the stilted classical style that had heretofore been used was more suitable for representing the new realities of the Meiji period. By the end of the Meiji era, naturalist (shizenshugi) writers Tayama Katai and Shimazaki Tōson were writing in a language closer to their everyday speech than they would have just two decades earlier.

The situation 1,000 miles southwest of Tokyo is a study in contrasts. Okamoto Keitoku and Nakahodo Masanori mark the appearance of fiction in Okinawa in 1908, some twenty years after it was established in the metropole.6 The reasons they posit for this delay have to do with the history of Okinawa, a region many perceived as lagging behind in Japan’s frenetic quest to modernize, beginning in the late nineteenth century.7 Another mitigating circumstance pertains to language, a present-day issue that came to the fore among writers in Okinawa in the Meiji period just as it did for writers then in Tokyo. Below, I consider reasons for the belated appearance of Okinawan fiction, describe the literary scene in Okinawa during the Meiji period, and read closely the works of Yamagusuku Seichū (1884–1949), the author of Okinawa’s first important work of fiction, “Mandarin Oranges” (“Kunenbo,” 1911).8 My aim is to identify what led critics to designate fiction written in Japanese as “Okinawan” in the first place. It is clear that demand for local color among the central literary establishment in the early 1900s9 precipitated a wave of fiction that featured southern island landscapes, but did these stories set in lush, semi-tropical Okinawa satisfy senior writers and critics in Tokyo and in Okinawa alike? More importantly, what criteria did critics use to categorize a particular work as Okinawan fiction?

A tumultuous history

In his history of modern Okinawan literature, Okamoto Keitoku makes frequent mention of the difficulties faced by writers in Okinawa.10 In the outline that follows, I will expound on the constraints Okamoto raises, and under which authors labored. To begin with, owing to its liminal status, the region underwent modernization later than the mainland. Although the Shimazu clan of Satsuma had been in control of the Ryukyus since their invasion of Okinawa in 1609, the Ryukyus remained an independent kingdom that paid tribute to both China and Japan (Nitchū ryōzoku). Overseas trade, generally forbidden in Japan under the Tokugawa regime, was permitted and even encouraged in the Ryukyus, affording the politically dominant Shimazu clan hefty profits. Economic exploitation took place in the agricultural sector as well, as the Shimazu rulers coerced islanders to produce sugar cane and submit to heavy taxes from the early seventeenth century.11 Thrust suddenly into Japan’s feudal society, Ryukyuans faced enormous contradictions. Once a prosperous seafaring people, the islanders now tilled soil. The kingdom, which had disallowed weapons since the rule of Shō Shin early in the sixteenth century, was overrun by sword-wielding samurai. I do not mean to assert here, as many entangled in contemporary identity politics do, the false notion that Ryukyu was Edenic prior to the Satsuma invasion. In fact, Ryukyu was divided into three separate areas, Hokuzan, Chūzan, and Nanzan, a situation that surely did not come about peacefully. Thus, given that the Shimazu clan was the de facto ruler of Ryukyu, “independence” was only nominal.

In 1879, Okinawa, the center of the Ryukyuan kingdom since the twelfth century, was incorporated into the Meiji state. The so-called Ryukyuan Disposition (Ryūkyū shobun) is a complex merger that has been construed variously Some view it as an “invasive militaristic annexation” enacted as part of the Meiji Government’s seemingly benign efforts to consolidate the nation, while others regard it as “a type of slave liberation” that freed the islanders from agricultural subjugation.12 Considering the timing of the annexation and the Meiji Government’s painstaking efforts to secure the region, one would be hard-pressed to consider the 1879 Disposition as anything other than the first of many similar encroachments made by a rapacious central government intent on consolidating a fledgling nation.13 However one interprets it, the annexation of Okinawa, followed by decades of intense cultural nationalism, which all but erased from people’s minds the region’s long-held ties to China, pressed islanders to adapt quickly to the demands of a new leadership, much as the Satsuma invasion had two and a half centuries earlier.14

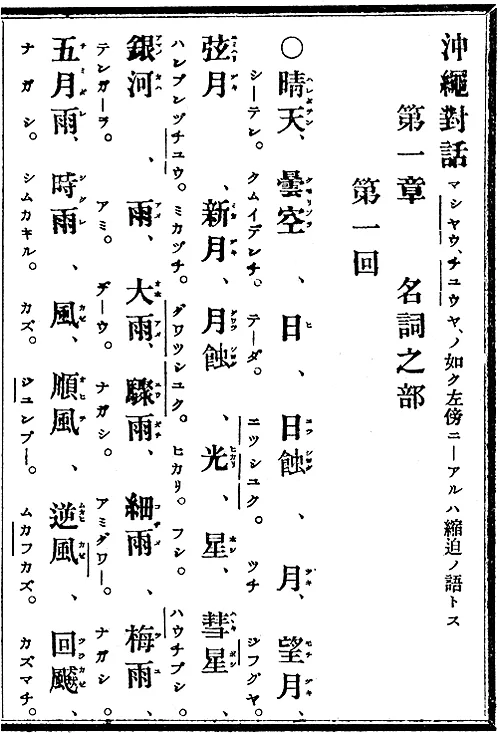

Elementary schools, key apparati for the inculcation of imperial worship, were quickly established in 1880, one year after Okinawa attained its prefectural status. The prime objective of Conversations in Okinawa (Okinawa taiwa), the first textbook in wide circulation, was to teach students how to speak in standard Japanese on a wide variety of subjects. Comprised of two volumes, each containing four chapters, the text covered the following topics: nouns, seasons, school, agriculture, business, pleasure, travel, and miscellany Individual chapters presented “typical” phrases in the standard language to be mastered with local-language equivalents for comprehension. In childhood reminisces, Okinawa’s first modern-day students often point to the oddities of the new curriculum. For instance, the section on seasons taught students how to converse on snowy weather (in balmy Okinawa, no less!) as follows:

SPEAKER A: The wind tonight is really cold.

Konban no kaze wa zuibun samou gozarimasu.

Chū nu kaze dotto himushi.

SPEAKER B: Yes, it is. It’s snowing a little more than it was a while ago.

Sō de gozarimasu. Sakihodo yori sukoshi yuki ga furite orimasu.

Yaya gēsā. Andēbiru. Namasachikara uhē yuchinu futouyabīshi.15

Despite how alien much of the Japanese terminology was, in the span of two decades, most Okinawans were convinced of the necessity to master it. Particularly conscientious were those who joined the military and émigrés to Hawaii; without knowledge of Japanese, these individuals would be putting their livelihoods at risk.

Naturally there was some resistance to the state-imposed language, but compliance was high, especially as Japan grew in strength. The state’s need to teach patriotism through emperor-centered and assimilationist education coalesced with the desires of Okinawans to better their lives, resulting in some 99.3 percent of the school-age population attending elementary school by 1902. When a fire razed Sashiki elementary school in 1910, burning with it the Emperor’s photograph, the school principal and teachers on duty were summarily dismissed from their positions.16 Education of the time held that Okinawa was Japan’s eldest son, Taiwan, its second son, and Korea, its third. Accordingly, education measures implemented in Okinawa, beginning in 1880, became the blueprint for colonial education in 1895 and 1910 when Taiwan and Korea became formal colonies.

In 1888, two years after his tenure on the island, Governor Uesugi Mochinori generously donated 3,000 yen for scholarships that would allow select students to travel to Tokyo for higher education.17 The first group of five students was particularly influential in shaping Okinawa’s future. The achievements of Jahana Noboru, Kishimoto Gashō, Takamine Chōkyō, Ōta Chōfu, and Nakijin Chōhan fill histories of the prefecture.18 The Iha brothers are two other well-known Okinawan enlightenment scholars whose contributions are impossible to ignore. Iha Fuyū, a linguist, is widely regarded as the father of Okinawan studies. His younger brother, Getsujō, a poet and literary critic, occupies an equally important role in the field of Okinawan literature. As these students began to return home, they disseminated newly acquired knowledge to others in Okinawa, thereby dramatically changing the social and intellectual landscape. From 1880 to 1907, the rate at which Okinawans were educated rose from 2 to nearly 100 percent, an indication of both the state’s nationalistic impulse and the islanders’ own desires to rid themselves of their perceived “backwardness.”19

Assimilation was by no means achieved without dissent. After Okinawa’s formal incorporation into the nation-state, vast numbers of residents resisted modernization. The emerging class of enlightenment thinkers who looked to Tokyo for models for modern art and science may have welcomed a uniform education system with an emphasis on standard Japanese, but others viewed this type of top-down modernization as a clear imposition and threat to Ryukyuan culture. Many, bewildered by the onslaught of new Japanese institutions, grew nostalgic for the old ways and aligned themselves with China rather than Japan.20 It was only after China’s defeat in the Sino-Japanese war of 1894–5 that Okinawans demonstrated fuller support of the Meiji Government. Thus, although Okinawa became part of the modern nation-state in 1879, a decade later than the main islands, another fifteen years would pass before the central government secured the widespread loyalty of the Okinawan people.

Figure 1 Okinawa’s first nationally endorsed textbook, Conversations in Okinawa.

As a result of Okinawa’s late incorporation into the nation, military conscription and prefectural assembly elections were in turn instituted several years after other areas of Japan, further compounding the notion that Okinawans were “behind.” Military conscription, particularly belated, was not established in Okinawa until 1898, more than two decades later than the rest of Japan. In fact, Okinawans were exempted from the 1873 Conscription Law because of residual doubts about their loyalty to the state.21 Even after conscription was implemented, evasion of military duty in Okinawa remained high because of the language barrier many Okinawan men feared they would face.22 Intellectual historian Kano Masanao traces the root of Okinawans’ self-consciousness in the late Meiji period to the “House of Peoples,” an exhibit in the Fifth Domestic Exhibition for the Promotion of Industry held in Osaka in 1903.23 The display showcased a hut in which a man, presumably Japanese, stands with whip in hand over a motley group that included Ainu, Taiwanese aborigines, and Okinawan prostitutes. Far more shocked by their inclusion among ethnic groups at a major urban exhibition than by the display’s inherent bias, Okinawans embraced Japanese systems with new fervor in order to rid themselves of social stigma.

In their desire to assimilate, Okinawans, particularly those in the nascent middle class, cast aside their local language, which, prior to the twentieth century was a central aspect of their identity Of course, as we have seen, the state, too, played a role by suppressing the use of non-normative language. As the dramatic rise in numbers of students attending elementary school indicates, standard language education grew in importance, effectively squelching the use of local speech for literary expression. By the third decade of Meiji, conditions necessary for the production of modern prose appeared to be in place. Elite students had returned from Tokyo eager to enliven the antiquated literary scene in which the medium of expression remained some variety of Ryukyuan speech, rather than standard language.24 In 1893, Okinawan writers in the Movement for Freedom and People’s Ri...