![]()

1 Introduction

In January 2008, leaders of the 27 Member States of the European Union gathered in Berlin to mark the 50th anniversary of the Treaty of Rome. The celebration included exhibits, music concerts and speeches and closed with a fireworks display in front of the Brandenburg Gate. Although the celebration was in Berlin, because Germany was holding the EU presidency at the time, a more appropriate location could not have been chosen. Emerging from the ashes of destruction, Germany, together with France and four other countries, forged the Rome Treaty to secure a European peace that would be sustained for future generations. Integrating Germany into a European institutional framework ensured it could never threaten its neighbors again. And, therefore, many believed Europe would never be plunged back into war, avoiding the repeat of the deaths of millions. As such, the Treaty of Rome, or the EC Treaty, accomplished a key European diplomatic and geostrategic goal.

By setting the foundation stone for future cooperation, the Treaty of Rome is a remarkable historical achievement for all of Europe. The European Union today represents a degree of international economic and political cooperation unprecedented in world history. With some exceptions, most think that the EU represents a great victory for all of its citizens. But the anniversary celebration, justifiably, ignores all of the moments in which progress was stopped and those who opposed it. Among the first failures was the rejection of the European Defense Community by the French Parliament in 1954. Then General Charles de Gaulle’s opposition to more supranational power for the EC led to the “empty chair” crisis in 1965. The United Kingdom’s application to join was rejected twice. The Maastricht Treaty was rejected in a Danish referendum in 1992 and barely passed in France. Finally, despite widespread optimism among political elites, the Constitution failed in Holland and France in 2005. The Irish electorate rejected its successor, the Treaty of Lisbon, until a second referendum approved it in 2009.

Opposition to European integration has not just come at important historical moments. It also occurs through the frequent practice of attempting to enforce the EC Treaty and other types of EU law. The Commission, as the guardian of the Treaties, is charged with ensuring that the Member States and their citizens are adhering to EU law. The instances that it discovers when a Member State violates EU law serve as small illustrations of opposition or reluctance of a government to integrate fully. Despite the large collective gains European integration has produced, some countries choose to maintain the status quo more often and as long as they can more than others.

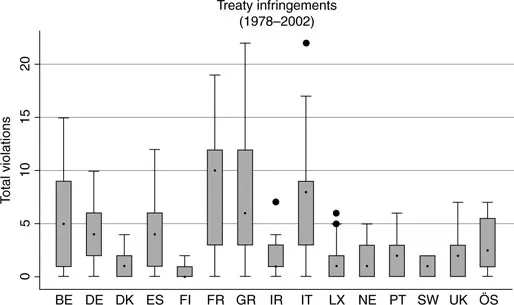

Figure 1.1 shows the cross-national variation in violations of EU law the Member States have committed just in the area of the EC Treaty and regulations based on it. Some of the most supportive members of the European project have violated the EC Treaty more than others that have been more skeptical. The single dot in the shaded box area represents the median number of infringements committed each year. The shaded areas surrounding the dot show the range of violations committed each year that fall within the range of the 25th and 75th percentile. The whiskers at each end encase the number of violations that occur each year that are within one quartile of this range. Marks outside the boxed areas represent the minimum and maximum number of violations committed in this time period.

Figure 1.1 Cross-national distribution of EU legal violations.

Source: European Commission Annual Reports.

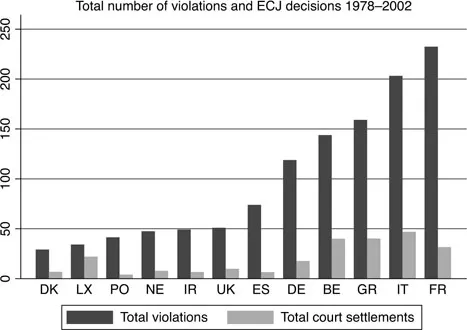

For example, even though both Italy and Greece receive a substantial amount of funds from the EU to develop their poorer regions, they commit the largest number of violations. In contrast, despite a strong antipathy to supranational authority, the United Kingdom appears to comply more often than some of the EU’s strongest supporters, such as Germany or France. In addition, some countries choose to delay complying with a suspected violation more than others. If the Commission discovers or confirms that a violation has taken place and the national government either does not reply or alter its behavior within the allotted time, the infringement case is referred to the European Court of Justice. Some countries are willing to risk an adverse ruling more than others (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 EU legal violations and ECJ decisions.

Source: European Commission Annual Reports.

The aim of this book is to provide a powerful but elegant model of noncompliance to account for why violations of EU law occur and why some violations escalate and are decided by the ECJ. Thus, noncompliance not only varies among the Member States of the EU, but with how governments choose to handle violations of EU law when they do occur.

More generally, these violations also show that political opposition to European integration has always existed and continues to grow. When national leaders wished, they withheld their support for more integration. When allowed, European voters expressed their disapproval at the ballot box. However, these moments are rare. Instead, most opposition to the policies of the European Union takes place through cases of noncompliance with EU law. By studying noncompliance and opposition to the process of European integration, this book sheds more light on the losers associated with European integration compared to the almost exclusive focus on the winners to this point.

The argument in brief

Despite the EU being one the most legalized regimes in the world, noncompliance occurs often. Although the European Commission and Court of Justice can punish states and individuals for noncompliance, violations still happen frequently. And there is a great amount of variation when they do. The number of violations committed varies across time and country. Some cases of noncompliance are settled sooner than others. Many suspected infringements are dismissed once Commission and national officials discuss them. On other occasions, albeit rare ones, a Member State is punished in the form of economic sanctions. This rich amount of diverse political behavior calls for an explanation that is comprehensive but yet parsimonious. This book aims to account for much of this variation by providing a simple but rigorous theory for why noncompliance occurs and why some legal violations are settled sooner than others.

What are the sources of noncompliance? Why does noncompliance vary across the Member States and over time? These questions are answered by looking at the domestic politics of international law. States face numerous countervailing political pressures when trying to comply with law beyond the nation state. On one side, international institutions, courts and even other regime members will call for a country to abide by its legal commitments. On the other side stand interest groups or other actors at the domestic level who demand their national governments not to comply in order to protect some economic or political advantage. Like many other issues in international politics, the situation resembles a two-level game.1 How national governments react to these counteracting pressures is the subject of this book.

Drawing on basic theories of collective action, I argue that compliance with international law is a public good for a country. Hypothetically, every country that belongs to an international regime benefits when each member of the regime fulfills its international legal obligations. Governments comply with international law for several reasons. First, states did not construct these agreements unless they achieve some material or social gain for their members. By complying with them, they secure these gains. Second, if there is a likelihood of more cooperation in the future, governments will comply even though they may suffer some short-term losses in exchange for long-term gains. Third, a state can begin to enjoy the benefits to its general reputation such that other states will want to cooperate with it in the future if it is perceived as having a good reputation as a strong “team player.”

Whether these benefits are actually realized depends on the type of public good and how it is produced. There are always dangers of free riding and thus the under-or even non-provision of the public good. Free riding is mostly likely to happen when the public good is nonrival and nonexclusive. It is considered nonrival if one member’s consumption does not affect another’s. It is nonexclusive when one or more members cannot be excluded from enjoying the public good without bearing high costs. Problems of coordination build up if the regime’s members are of different sizes or have different levels of interest in the production of the public good. Unless a large member can produce enough of the public good that every member will enjoy, there is significant chance that too little of the public good will be provided, or none at all. Thus, members of international regimes create institutions to monitor agreements and to ensure that violators are punished. Only when the costs of cheating exceed its benefits will states choose to comply.

International organizations must secure a certain level of compliance in order for the public good to be produced. Thus, they are awarded the powers of sanctioning possible offenders (Axelrod and Keohane 1985, Downs et al. 1996, Olson 1965, Underdal 1998). They also can provide incentives for states to comply through financial or technical assistance. Whether carrots or sticks are used to secure compliance summarizes the basic difference between the enforcement and management schools of compliance (Chayes et al. 1998, Young 1992). While monitoring and punishment are used to increase the costs of cheating, technical and financial assistance are used to help a country realize the benefit of cooperation.

There is a long debate over which method is most effective to secure compliance. Tallberg (2002) argues compliance is most likely to happen when the tools of both schools are used. But neither school examines why one method works in some circumstances and not in others. Whether a stick or a carrot works to secure compliance depends on the source of a government’s calculus to comply. When a government will shirk its international legal responsibilities and when it will surrender to the wishes of its domestic constituents depends on how it weighs the costs and benefits based on factors at home. When a state achieves the goals of cooperation, those benefits usually benefit the entire country, but the costs of complying are concentrated among a small group of people. More importantly, the origins of noncompliance remain uninvestigated. For example, if we consider a ban on the use of chemical weapons on the battlefield or in general, national militaries as well as citizens will benefit if they are not used. However, the industries that produce and sell these weapons will suffer from a decline in demand for their products. These firms are then rationally motivated to ask their governments either to cheat or to shirk their international legal responsibilities.

Because the costs of compliance are usually concentrated, those groups opposed to compliance will pressure their governments to refrain from changing the status quo. They are usually the first ones to discover what the effects of compliance will be. They have strong incentives to monitor EU legislation to see how it will affect them. A Member State’s regulations may not just be discriminating against the import of goods from another Member State. They are also protecting native industries or firms from European competition. As a result, those opposed to compliance become immediately aware of what state practices do not meet their country’s legal obligations because they benefit the most from noncompliance.

Those groups who oppose compliance will form associations and lobby their governments to reject changes to the status quo demanded by international institutions or other regime members. They organize opposition by publicizing their disputes with their national governments. These groups stage rallies and generate sympathy from the surrounding public. They frame their arguments with national and European officials by characterizing their disputes as a struggle between national autonomy or sovereignty and the arbitrary actions of unelected, remote and, sometimes, illegitimate international institutions. While their true motivations lie in protecting their own self-interests, blaming international institutions for demanding undesired change often generates sympathy, such as when the IMF imposed austerity measures during the Asian financial crisis of the 1990s. They also can threaten to hold their nationally elected legislators to account by working for their defeat in future elections.

National governments then must make a difficult choice. They must navigate between the Charybdis of displeasing their domestic constituencies by complying with their international legal obligations and the Scylla of shirking their responsibility under international law. A government’s choice between the two depends on the strength of domestic opposition and the carrots and sticks that international institutions threaten or offer to national governments to obtain their compliance. In some circumstances, when domestic opposition is strong, governments will not comply until an international court makes a ruling in the matter. Governments can then justify changes to the status quo that harm powerful constituents or interest groups as being necessary for several reasons. First, they may cite their general obligation to abide by international law, a norm that all modern states follow. Second, they are wary of sacrificing the long-term gains of future cooperation to satisfy the demands of a powerful domestic constituency. Third, governments could fear retaliatory actions by other regime members, whereby their countries’ own goods and products are discriminated against. If governments choose to violate legal norms related to the treatment of prisoners of war, their own troops could face similar treatment by other countries or groups. Thus, not every government is willing to risk future increased costs or decreased benefits by refusing to comply.

There are circumstances in which governments can avoid this dilemma. First, governments can always comply immediately with their obligations. They comply either because their current policies satisfy their legal requirements or because domestic opposition to changing the status quo fails to materialize. Second, they can avoid the dilemma by refusing to comply at all. Governments can choose to maintain compliance either because the risk of offending domestic constituencies is too great, such as their own political survival, or the costs of compliance simply exceed the benefits as perceived at the time. For example, while states will commit to maintaining an exchange rate within a specific range of values, a change in international economic conditions or some other exogenous shock to the system, such as a severe financial crisis, can force governments to violate their previous agreements. None of the other incentives to maintain cooperation or disincentives to avoid defection will be effective.

The range of choices governments have in order to deal with conflicts between national policies and international law shows that state behavior is more than a simple dichotomy between compliance and noncompliance. Rather, state behavior ranges from complete compliance, or what I call obedience, to complete noncompliance, which I term refusal. In the case of the former, no changes to the national status quo are necessary for a state to satisfy its international legal obligations. In the case of the latter, a government will fail to comply despite any threats of punishment for defection or incentives to maintain its cooperation. In between, there are two other types of compliance behavior. The first, termed accommodation, is when important changes to the national status quo must be made to comply but domestic opposition fails to develop. As a result, compliance takes place swiftly and without difficulty. In contrast, the final and fourth type of compliance behavior is reluctance. Reluctance occurs when domestic opposition is strong and the government will refuse to comply until the stakes of noncompliance become too great. This may include disobeying an international court ruling, retaliatory behavior from other regime members, or the risk of jeopardizing future gains of cooperation. Chapter 2 unpacks more of the elements of each type of behavior. It also specifies the conditions under which each type of compliance behavior is expected and which institutional or political factors can lead to some types of behavior occurring in some countries more often than in others.

The sources of noncompliance

Why do violations of international law occur? The character of the violations depends on the type of actions an international agreement is either trying to foster or curtail. However, all violations happen because of some gap between the goals of an international agreement or law and current state behavior. The full consequences of an international agreement can rarely be anticipated. Regime signatories will attempt to specify the prescriptions and proscriptions associated with an agreement as effectively and precisely as they can. However, unanticipated consequences and unintended effects almost always occur because of the inherent limitations national leaders face in gauging the future effects of their actions. Incomplete information, vague legal language and general uncertainty lead to the discovery of new state practices that are not conforming to an international legal obligation.

In the case of the European Union, many violations occur as the regulatory barriers or special privileges firms enjoy from national regulations come under the scrutiny of the Commission. In an effort to complete the single internal market, the Commission grew increasingly skeptical of the efforts governments made to protect particular industries from European competition. Many of the quantitative barriers to EU trade had already fallen with the completion of the customs union. The Commission increasingly turned toward the qualitative regulatory barriers that discriminated against goods from other EU Member States. Yet those barriers secured a dominant position for particular firms or industrial sectors. For example, the requirement in Germany for all beer to be limited to four ingredients gave German brewers a decisive advantage within the German market.

Among the EU Member States, economic integration has already produced significant amounts of economic convergence among national industries such that relative prices are not the primary source of competition. Instead, competition is between groups of firms within the same industry along the lines of quality and taste or some non-quantitative advantage. For example, unfair trade advantages for domestic firms also occur because of special financial relationships with the state that serve as indirect subsidies. As competitive pressures grew, the regulatory practices that gave some groups of firms within a particular industry a specific trade advantage became subject to the Commission’s scrutiny. In short, the multiple practices states use to protect their own firms from European competition are the source of most legal infringements related to the single European market.

Through the development of EU case law, the European Commission created a robust legal doctrine that specified when these non-tariff barriers contradicted the EC Treaty. When there are few to no violations in a specific area, the state is in obedience. When t...